I would like to share few quotes, excerpts and author's deep work on philosophy, life and words of wisdom from this must read novel called "Man’s Search for Meaning"

with my followers and fellow steemitians.

This novel is an account of incidences that took place in the life of "Viktor Frankl " while he was a captive prisoner

at four different Nazi concentration camps—Theresienstadt, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Kaufering, and Türkheim, part of the Dachau complex.

His perspective and narratives of his fellow prisoner's life are accounted in this novel that describe instances of horrors and hope.

“He who has a Why to live for can bear almost any How.”

At one point, Frankl writes that a person “may remain brave, dignified and unselfish,

or in the bitter fight for self-preservation he may forget his human dignity and become no more than an animal.”

"No man should judge unless he asks himself in absolute honesty whether in a similar situation he might not have done the same"

A man’s character became involved to the point that he was caught in a mental turmoil which threatened all the values he held and threw them into doubt.

Under the influence of a world which no longer recognized the value of human life and human dignity, which had robbed man of his will and had made him an object to be exterminated under this influence the personal ego finally suffered a loss of values. If the man in the concentration camp did not struggle against this in a last effort to save his self-respect,

he lost the feeling of being an individual, a being with a mind, with inner freedom and personal value.

He thought of himself then as only a part of an enormous mass of people; his existence descended to the level of animal life.

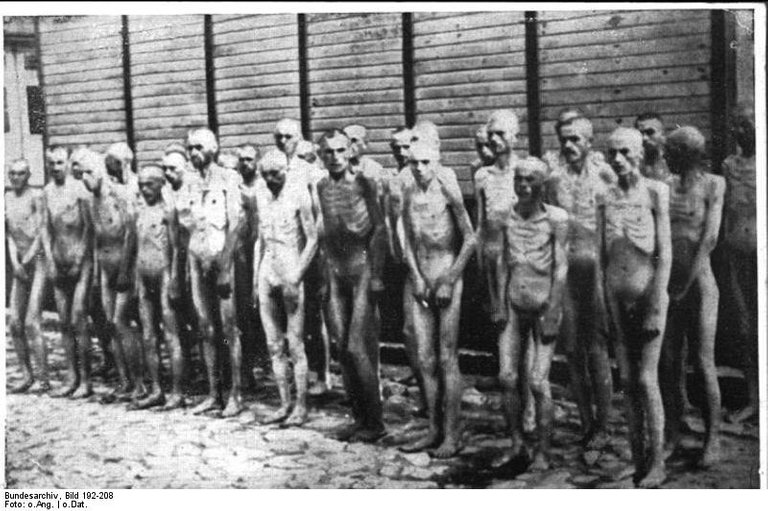

The men were herded—sometimes to one place then to another; sometimes driven together, then apart—like a flock of sheep without a thought or a will of their own. A small but dangerous pack watched them from all sides, well versed in methods of torture and sadism. They drove the herd incessantly, backwards and forwards, with shouts, kicks and blows. And we, the sheep, thought of two things only—how to evade the bad dogs and how to get a little food.

Frankl’s most enduring insight:

"Forces beyond your control can take away everything you possess except one thing, your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation. You cannot control what happens to you in life, but you can always control what you will feel and do about what happens to you."

“Honor thy father and thy mother that thy days may be long upon the land.”

“There is a sign, Auschwitz!” Everyone’s heart missed a beat at that moment.

Auschwitz—the very name stood for all that was horrible: gas chambers, crematoriums, massacres.

Slowly, almost hesitatingly, the train moved on as if it wanted to spare its passengers the dreadful realization as long as possible: Auschwitz!

People waiting for their turn in gas chambers

“I do not forget any good deed done to me, and I do not carry a grudge for a bad one.”

"The salvation of man is through love and in love"

I understood how a man who has nothing left in this world still may know bliss, be it only for a brief moment, in the contemplation of his beloved. In a position of utter desolation, when man cannot express himself in positive action, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way —an honorable way—in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfillment. For the first time in my life I was able to understand the meaning of the words, “The angels are lost in perpetual contemplation of an infinite glory.”

“Set me like a seal upon thy heart, love is as strong as death.”

To discover that there was any semblance of art in a concentration camp must be surprise enough for an outsider,

but he may be even more astonished to hear that one could find a sense of humor there as well; of course, only the faint trace of one, and then only for a few seconds or minutes. Humor was another of the soul’s weapons in the fight for self-preservation.

It is well known that humor, more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an aloofness and an ability to rise above any situation, even if only for a few seconds.

The story of Death in Tehran -

" A rich and mighty Persian once walked in his garden with one of his servants. The servant cried that he had just encountered Death, who had threatened him. He begged his master to give him his fastest horse so that he could make haste and flee to Tehran, which he could reach that same evening.

The master consented and the servant galloped off on the horse. On returning to his house the master himself met Death, and questioned him, “Why did you terrify and threaten my servant?” “I did not threaten him; I only showed surprise in still finding him here when I planned to meet him tonight in Tehran,” said Death."

Despite that factor—or maybe because of it—we were carried away by nature’s beauty, which we had missed for so long.

In camp, too, a man might draw the attention of a comrade working next to him to a nice view of the setting sun shining through the tall trees of the Bavarian woods (as in the famous water color by Dürer), the same woods in which we had built an enormous, hidden munitions plant. One evening, when we were already resting on the floor of our hut, dead tired, soup bowls in hand, a fellow prisoner rushed in and asked us to run out to the assembly

grounds and see the wonderful sunset. Standing outside we saw sinister clouds glowing in the west and the whole sky alive with clouds of ever-changing shapes and colors, from steel blue to blood red. The desolate grey mud huts provided a sharp contrast, while the puddles on the muddy ground reflected the glowing sky. Then, after minutes of moving silence, one prisoner said to another, “How beautiful the world could be!”

We can answer these questions from experience as well as on principle. The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action. There were enough examples, often of a heroic nature, which proved that apathy could be overcome, irritability suppressed. Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress. We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. And there were always choices to make. Every day, every hour, offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your very self, your inner freedom; which determined whether or not you would become the plaything of circumstance, renouncing freedom and dignity to become molded into the form of the typical inmate.

Dostoevsky said once, “There is only one thing that I dread: not to be worthy of my sufferings.”

An active life serves the purpose of giving man the opportunity to realize values in creative work, while a passive life of enjoyment affords him the opportunity to obtain fulfillment in experiencing beauty, art, or nature. But there is also purpose in that life which is almost barren of both creation and enjoyment and which admits of but one possibility of high moral behavior: namely, in man’s attitude to his existence, an existence restricted by external forces. A creative life and a life of enjoyment are banned to him. But not only creativeness and enjoyment are meaningful. If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death.

Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete. The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the suffering it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity—even under he most difficult circumstances—to add a deeper meaning to his life.

"Everywhere man is confronted with fate, with the chance of achieving something through his own suffering."

"With the end of uncertainty there came the uncertainty of the end"

Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, which contains some very pointed psychological remarks. Mann studies the spiritual development of people who are in an analogous psychological position, i.e., tuberculosis patients in a sanatorium who also know no date for their release. They experience a similar existence—without a future and without a goal.

Bismarck - “Life is like being at the dentist. You always think that the worst is still to come, and yet it is over already.”

"Emotion, which is suffering, ceases to be suffering as soon as we form a clear and precise picture of it."

"It did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us."

We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life, and instead to think of ourselves as those who were being questioned by life—daily and hourly. Our answer must consist, not in talk and meditation, but in right action and in right conduct.

Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual.

Questions about the meaning of life can never be answered by sweeping statements.

“Life” does not mean something vague, but something very real and concrete, just as life’s tasks are also very real and concrete. They form man’s destiny, which is different and unique for each individual. No man and no destiny can be compared with any other man or any other destiny.No situation repeats itself, and each situation calls for a different response. Sometimes the situation in which a man finds himself may require him to shape his own fate by action.

At other times it is more advantageous for him to make use of an opportunity for contemplation and to realize assets in this way. Sometimes man may be required simply to accept fate, to bear his cross. Every situation is distinguished by its uniqueness, and there is always only one right answer to the problem posed by the situation at hand. When a man finds that it is his destiny to suffer, he will have to accept his suffering as his task; his single and unique task. He will have to acknowledge the fact that even in suffering he is unique and alone in the universe. No one can relieve him of his suffering or suffer in his place. His unique opportunity lies in the way in which he bears his burden.

Rilke spoke of “getting through suffering” as others would talk of “getting through work.”

There was plenty of suffering for us to get through. Therefore, it was necessary to face up to the full amount of suffering, trying to keep moments of weakness and furtive tears to a minimum. But there was no need to be ashamed of tears, for tears bore witness that a man had the greatest of courage, the courage to suffer.

Nietzsche: “Was mich nicht umbringt, macht mich stärker.” (That which does not kill me, makes me stronger.)

“Was Du erlebst, kann keine Macht der Welt Dir rauben.” (What you have experienced, no power on earth can take from you.)

There are two races of men in this world, but only these two—the “race” of the decent man and the “race” of the indecent man are found everywhere; they penetrate into all groups of society. No group consists entirely of decent or indecent people. In this sense, no group is of “pure race"

“I called to the Lord from my narrow prison and He answered me in the freedom of space.”

Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation in his life and not a “secondary rationalization” of instinctual drives.

This meaning is unique and specific in that it must and can be fulfilled by him alone; only then does it achieve a significance which will satisfy his own will to meaning. There are some authors who contend that meanings and values are “nothing but defense mechanisms, reaction formations and sublimation.” But as for myself,

I would not be willing to live merely for the sake of my “defense mechanisms,” nor would I be ready to die merely for the sake of my “reaction formations.” Man, however, is able to live and even to die for the sake of his ideals and values!

Schopenhauer - Mankind was apparently doomed to vacillate eternally between the two extremes of distress and boredom.

In actual fact, boredom is now causing, and certainly bringing to psychiatrists, more problems to solve than distress.

And these problems are growing increasingly crucial, for progressive automation will probably lead to an enormous increase in the leisure hours available to the average worker. The pity of it is that many of these will not know what to do with all their newly acquired free time.

Let us consider, for instance, “Sunday neurosis,” that kind of depression which afflicts people who become aware of the lack of content in their lives when the rush of the busy week is over and the void within themselves becomes manifest.

Not a few cases of suicide can be traced back to this existential vacuum. Such widespread phenomena as depression, aggression and addiction are not understandable unless we recognize the existential vacuum underlying them. This is also true of the crises of pensioners and aging people.Moreover, there are various masks and guises under which the existential vacuum appears. Sometimes the frustrated will to meaning is vicariously compensated for by a will to power, including the most primitive form of the will to power, the will to money. In other cases, the place of frustrated will to meaning is taken by the will to pleasure. That is why existential frustration often eventuates in sexual compensation. We can observe in such cases that the sexual libido becomes rampant in the existential vacuum. An analogous event occurs in neurotic cases. There are certain types of feedback mechanisms and vicious-circle formations which I will touch upon later. One can observe again and again, however, that this symptomatically has invaded an existential vacuum wherein it then continues to flourish.

“Live as if you were living already for the second time and as if you had acted the first time as wrongly as you are about to act now!”

It seems to me that there is nothing which would stimulate a man’s sense of responsibleness more than this maxim, which invites him to imagine first that the present is past and, second, that the past may yet be changed and amended. Such a precept confronts him with life’s finiteness as well as the finality of what he makes

out of both his life and himself.

"The more one forgets himself—by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love—the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself."

Love is the only way to grasp another human being in the innermost core of his personality. No one can become fully aware of the very essence of another human being unless he loves him. By his love he is enabled to see the essential traits and features in the beloved person; and even more, he sees that which is potential in him, which is not yet actualized but yet ought to be actualized. Furthermore, by his love, the loving person enables the beloved person to actualize these potentialities.

By making him aware of what he can be and of what he should become, he makes these potentialities come true.

“The wish is father to the thought” = “The fear is mother of the event.”

"Man is that being who invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord’s Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips"

"A human being is not one in pursuit of happiness but rather in search of a reason to become happy."

It is true that the old have no opportunities, no possibilities in the future. But they have more than that. Instead of possibilities in the future, they have realities in the past—the potentialities they have actualized, the meanings they have fulfilled, the values they have realized—and nothing and nobody can ever remove these assets from the past.

In view of the possibility of finding meaning in suffering, life’s meaning is an unconditional one, at least potentially.

That unconditional meaning, however, is paralleled by the unconditional value of each and every person.

It is that which warrants the indelible quality of the dignity of man.

Just as life remains potentially meaningful under any conditions, even those which are most miserable, so too does the value of each

and every person stay with him or her, and it does so because it is based on the values that he or she has realized in the past, and

is not contingent on the usefulness that he or she may or may not retain in the present.

"You must realize that the world is a joke. There is no justice, everything is random. Only when you realize this will you understand how silly it is to take yourself seriously. There is no grand purpose in the universe. It just is. There’s no particular meaning in what decision you make today about how to act.”

"I recommend that the Statue of Liberty on the East Coast be supplemented by a Statue of Responsibility on the West Coast."

“It is we ourselves who must answer the questions that life asks of us, and to these questions we can respond only by being responsible for our existence.”

Nice !

i like your work.keep it up

i follow you now you follow me and upvote lets's work together

Sure. Thanks for your comment.

Congratulations @digitalfortress! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP