<...> Mature technological systems - cars, roads, centralized water supply, sewerage, telephone, rail, weather forecasts, buildings and often computers - exist as a natural background, as commonplace and invisible as trees, daylight or dirt. Although all of our civilization belongs to them, these technological systems are only noticeable when they are out of order, which happens rarely. They are interconnecting modern fabric and circulation systems.

Paul Edwards, Infrastructure and Modernity (Infrastructure and Modernity)

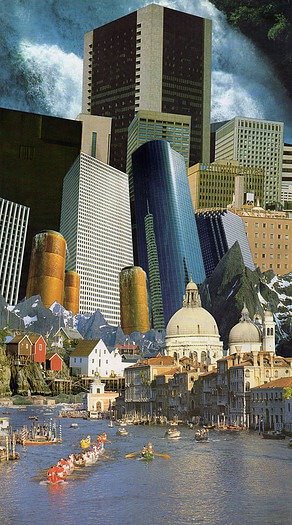

picture author:David Delruelle : Lost in Connection

Infrastructures are not just a useful tool but an integral part of society: science and technology historians and sociologists say that more than three decades ago. Inspired by Thomas Hughes's significant studies of technical systems, scientists from different fields have rethought the creation of states, political regions, and even the planet Earth itself as the construction of technical infrastructures. However, the idea that infrastructure is not only a constructed, passive object, but also an active player still has a place in traditional humanities and in social imagination. However, changing the direction of thinking is not easy, especially if we are talking about infrastructure. According to American historian Paul Edwards, well-functioning infrastructure is simply invisible as the purpose of infrastructure is to lay the foundations for other activities - to enable people to constantly change their goals and practices. We notice only poorly functioning infrastructure. As Edwards writes, this is because we have a habit of distinguishing between social processes and material infrastructure as essentially different things. It is believed that social and political values are shaped according to their own logic, and that infrastructure is perceived simply as a form that does not act as something silly and universal. For example, asphalt roads run in machinery and dictatorships, and in liberal democracies. Social networks are used by authoritarian propaganda, marketing departments, and radical anarchists. The technology seems to be neutral. Such simplification undermines our understanding: Edward calls for this approach to be rejected on the basis of the French philosopher Bruno Latour. He argues that infrastructures are socio-political: their design, use and maintenance require a form of special social organization, and changes bring about changes in politics and in the community.

In this context, it is worth rethinking the transformations of the Baltic States through the infrastructure as a prism of socio-political assemblage. Like Edwards, I think it's time to focus on silent, invisible infrastructures in order to create their own policies and to critically evaluate their role in shaping both day-to-day life and geopolitics.

Focusing on infrastructure means creating some kind of revolution. In the context of Baltic historiography in academic literature, the political transformation of the Baltic States is usually viewed as a cultural and political, ideological struggle in which the locals seek to escape from the colonial regimes imposed on Swedish, German, and Russian. The historians have clearly shown to us that the founders of the Baltic nations have constructed their countries as ethnographic spaces, distinguishing language and cultural peculiarities: lifestyle, songs, applied and visual arts, and literary narratives. I have been writing about how a sophisticated and pragmatic strategy to create meaning has been used to construct the Balts, which created the conditions for the emergence of what I call the geopolitics of cultural isolation.

However, a frequent foreign traveler, visiting Estonia, Latvia or Lithuania, first faces not with a song or a historical narration, but with a particular type of infrastructure. For example, travelers from the eighteenth century, traveling around Eastern Europe, described paths that were not lost and were laced with comfortable eateries; And travelers in the 1990s were faced with impractical airports, unheated hotel rooms and dilapidated cities. Infrastructure was overtaken by local representatives of public relations, armed with publicity stories, directly denoting the region's past.

In this example, I want to invite the reader to discover and explore infrastructures as central political utopias that shape the history and future of Baltic societies. If national cultures, which are truly traditions established, seek to transform the future by selectively updating the past, the infrastructure will deliver the future. In Lithuania, we have to develop a new conceptual apparatus and visual language that allows us to describe future-oriented infrastructure activities. This is a difficult but necessary task, and I will discuss some of the possible aspects of this essay.

Atheism

Time is perhaps the most important factor contributing to the invisibility of the infrastructure. Different infrastructures are characterized by different temporal patterns: roads are built to serve the age, similar to masonry dwelling houses, and manufacturing industry planners are only designing for decades to come. Once installed infrastructures impose their timeliness on biopolitics and the economy. For example, the first nuclear power plants built in the 1950s and 1960s had to operate for about thirty years; State planners have shaped industrial and social development within the limits of such a long term future energy perspective. Blocked apartments built in the 1960s and 1970s are expected to serve for three decades; Even long-term socio-economic forecasts, for example, in the fields of education and social care, were made for the same period.

If the position of everyday life makes it impossible to fully imagine the life of our lives for three decades, the long-term future of infrastructure seems clear and familiar. It is the long-term future of the infrastructure that brings it closer to the natural world. In everyday life we perceive the infrastructure as a stable environment that can be driven by our personal time, changing desires and needs. However, if we change our epistemological position, the stability of time disappears. As Edwards notes, the infrastructure of time is relational: the infrastructure seems to be durable only because the daily activities of a person are short-lived, and from the perspective of geo-history of the earth, human-made infrastructure is a fragile crater on the body of the old plan. As we study the social, material and natural future of our future, we can think of building a society as a brutal mastery of the components drawn from the future archive.

Reshaping from a short-term to a long-term future is not just an intellectual exercise, it's an asymmetrical power-penetrated practice. We can not always see this, because the daily, self-evident use of the term eclipses important aspects of this dimension. The relationships of atheism and power can be clarified through the separation of Barbara Adam between the present and future. Future present] and future of the present. Present futures]. According to Adam, the future of the future refers to the future as a gift, which can be seen and understood in an effort. The main problem for the future, understood as the future of the present, is technical: to provide adequate knowledge and to find the right tools for gathering and processing information. Shamans and prophets engage in such a future disclosure. The future of the future means what's coming. As Adam writes, "the future is imagined, planned, designed and manufactured for the future and future ".

The future of the future supports the existential hierarchical systems of knowledge and power, and the future of the future calls for the democratization of the future. The tension between these two models is evident when the infrastructure of the Baltic States is focused on predictability, power and aesthetics.

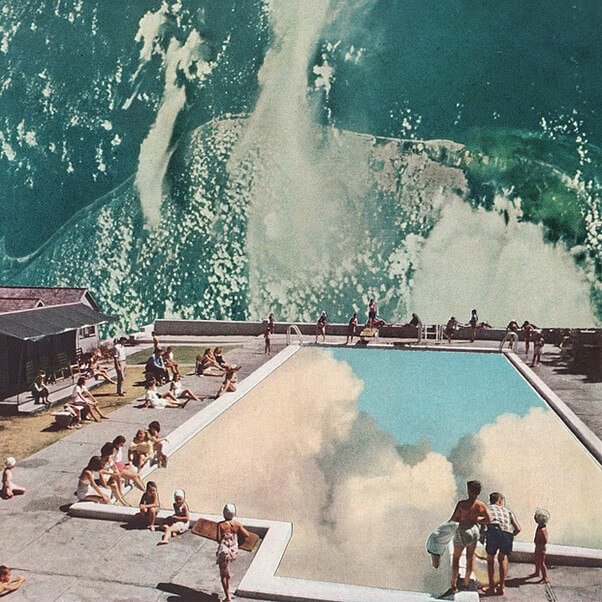

David Delruelle: Rapid Eye Movement

Predictability

We can play detectives and find the infrastructures that are silent in the socio-political studies of the Baltic States. Historians often use intuitively the infrastructural futures, use it as a context for "true" political and social events. In traditional historiography, infrastructure is a general predictor denominator that allows you to creatively chase the historical process of chess. This is the natural infrastructure - rivers, lakes and marshes. Historians like to say about the marshland as strategic equipment during the Middle Ages: for example, a Lithuanian-built kūlijrindas network, consisting of secret underwater paths, allowed them to be invaded by intruders, knights of the Teutonic Knights, and escaped the dead. A newer human-made infrastructure is already visible as a trail of colonialism: this is the present railway network built by industrialists in the Russian Empire in the 1800s and connecting the lands of the Baltic region to the imperial technical space, connecting Warsaw, Kaunas and St. Petersburg.

It seems that in Baltic historiography natural infrastructure is interpreted as an integral part of national security and sovereignty, and the modern infrastructure created by human hands is associated with colonial rule and is portrayed as a witness to the delayed economic growth.

Meanwhile, the history of Western Europe is often spoken of as a progressive infrastructure design perspective. This is especially true in postwar studies. After the Second World War, the reconstruction of the infrastructure was closely linked to the new political status quo in Europe, and not only in the West, but also in the East. In our region, a new assembly of the "Soviet Baltic" infrastructure has been constructed, reflecting the visionaries of the Soviet future planners and forecasters. As the British anthropologist Caroline Humphrey reminds us, Soviet power was based on the Marxist idea that the social order is determined by the material base, and therefore the infrastructure. Humphrey argues that Soviet ideology was expressed not only in texts but also in architectural industrial projects . Still, science and technology studies (STS) allow us to go even further: we should not identify the Soviet infrastructure with the Soviet ideology, and look more closely at the complex and multi-sensory ways in which the infrastructure influenced the socium of the Baltic states.

An important feature of the Soviet planning system was that industrial plans that were dropped from the center were often adapted, sometimes subversive, in the local context. On the other hand, although in the Soviet system some important infrastructure initiatives also came from the bottom, the result was quite homogeneous. Huge mono-industrial cities penetrated into the countryside, narrow and straight roads traced the Baltic forests, bored geometry marked the contours of villages and towns in newly built neighborhoods - this aesthetics of infrastructure characterized the three Baltic countries as easily recognizable Soviet spaces with a predictable, future-oriented Soviet infrastructure.

At the same time, other developers of the "iron curtain" in Europe developed a European post-war vision expressed in the projects of integrated infrastructure embodying a sustainable future. Historians Per Högselius, Arne Kaijser and Erik van der Vleuten refer to these post-war planners as "European System Builders". By constructing integrated infrastructure projects, these builders sought to protect the future of Europe from war crashes, and even the "Iron Curtain" was not able to restrict their ambitions and imagination. In the 1950s, the Swedish social reformer Gunnar Myrdal proposed to integrate the socialist Eastern Europe into Western Europe and connect it to the road network. The idea of Myrdalis to follow the socio-political integration of infrastructure was the construction, use and care of the road network as a strategic tool to prevent future wars.

The economic and political aspects of infrastructure should already be sufficiently clear. Governments investing in infrastructure are considered to be predictable actors who care about the future. The post-soviet Baltic countries are also intended to integrate into the long-term infrastructure of the future of Europe. The World Bank has been demanding from 1994 that the Baltic governments include in their budgets a "separate line" of public investment in infrastructure. Economists believe that such investments reliably reflect economic growth, and with such information the new states become more predictable. However, others criticized this view, arguing that infrastructure development does not help predict political stability and economic growth. This is because different countries use different definitions of what infrastructure is. According to economist Christiano von Hirschhausen, for the first post-Soviet decade, the Baltic Government's infrastructure only supported energy and transport, sometimes even including agriculture. Intellectual infrastructure, education and science have been pushed out of the economic future of the planning horizon. Secondly, the actual level of investment varied from government programs: in the 1990s, the Baltic Government executed just one-third of the planned infrastructure investments. The Baltic governments tried to stick to the vision of the creators of the European system, but acted very slowly when it was necessary to develop and implement large projects, such as the energy bridge between Lithuania and Poland.

There are many reasons for the lack of infrastructure development during the first post-Soviet decade, but social strike seems to play a more important role than economic difficulties .

The fact that the Baltic States have invested so slowly in the infrastructure only confirms the idea of the sociologist Star: it is wrong to assume that there is always one main character, for example, the ministry responsible for infrastructure. Indeed, responsibility for it is widespread: infrastructure is a vast, multifaceted system that can only be partially changed, and can never be reworked substantially .

Infrastructure always comes up gradually - they grow up and are not mechanically lowered from the top .

Interestingly, some economists in development claim that there is practically no statistically significant relationship between infrastructure investment and economic growth. The macroeconomic impact of infrastructure investments is doubtless.

How then can you explain the still-existing attitude that economic prosperity will come only with the latest infrastructure? I would say that the infrastructure myth, even its fetishism, holds precisely because of the importance of infrastructure at a micro level - large projects provide tangible benefits to sufficiently dispersed recipient groups. The tension between the illusion of macro-predictability and the reality of micro-level profits make us turn to power.

Power

In the case of infrastructure, the power-knowledge ratio, in terms of Michel Foucault's terms, is deeply asymmetrical. Recently, the history of the Baltic States overlaps with these examples of asymmetry, but I would like to invoke the case of the Lithuanian Nuclear Power Plant, because it has a particularly well-defined asymmetric configuration of future energy. It should be remembered that the construction of a new energy infrastructure was hugging the core of the Communist project. In 1917, Lenin published the slogan: "Communism is the Soviet power and the electrification of the whole country!" The Soviet nuclear energy sector, which emerged after the Second World War, was used as a proof of Soviet technological and geopolitical superiority. Indeed, the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) reactors, launched in 1983, at that time were the most powerful in the world.

Initially, the inhabitants of Lithuania considered the Ignalina NPP as a colonial Soviet project, as only a few Lithuanian engineers participated in its construction. After the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, the Ignalina NPP found itself at the epicenter of the protests of national and nature protection movements, since the Ignalina reactors were of the same type as the RBMK, as in Chernobyl. Since the international agreement on the need to strengthen the safety of the power plant, since 1992, Sweden has been financing and advising a power plant. The closure of the Ignalina power plant was one of the cornerstones of the process of Lithuania's integration into the European Union. However, in 2009, a new political movement arose after the reactor was shut down. The process of nationalization of the former Soviet Russia's power plant and its closure procedures created a new Lithuanian expert community of atomic energy, which was committed to extending the atomic future. Unlike in the 1980s, when the Ignalina power plant was attacked as a Soviet colonial heritage, in 2009, articles in the Lithuanian media shimmers that the closure of a power plant shows the lack of an independent solution, even a political sovereignty. A group of interest has been formed requiring the construction of a new Visaginas nuclear power plant. Still, in the referendum of 2012, 62% The Lithuanian people voted against the atomic future - this is an unprecedented case in which the construction of a national infrastructure is determined democratically.

The disputes over the Visaginas power plant and the referendum led to a completely new type of discussion about what the Lithuanian society has the legitimate power to decide on the future of infrastructure. According to Star, different people in different contexts can have a very different infrastructure. Indeed, we can talk about social exclusion, where knowledge of the structure, benefits and future of infrastructure is socially segregated .

After all, the very concept of infrastructure is elitist: only a decision-making elite will have access to a panorama of planned infrastructure systems in the future; Only they have a clear understanding of the functioning of the infrastructure as long as it operates. And vice versa: the average citizen faces the fact of the existence of infrastructure only when the automation of everyday life is interrupted: there is a lack of a pipe, the main road is being repaired, when the heating is insufficiently heated or when heating prices are suddenly dancing up.

For an ordinary person, the infrastructure appears through interruptions of the present. In everyday life people think of using individual items, but there are no single objects in the grand designer's world, since all things are relative to him - integrated into functional and time chains.

Nevertheless, the situation in Visaginas NPP revealed that the decision-making elite infrastructure is concerned not only with future control but also with projected short-term profit opportunities. In this case, durability can become an ideology coupled to short-term goals. Thus, the infrastructure is included in the ideological discourse as a word that captures enormous public spending. The business elite is relying on a stability consonant with infrastructure, although in reality the infrastructure's distribution is unevenly distributed. This asymmetrical mode of power and knowledge best reveals aesthetics.

Aesthetics

Infrastructure policy plays a special role in aesthetics. The daily experience of infrastructure is best described as inexperience. As I said, infrastructure is expected to function and not be seen. However, everything changes with the opening of the normally closed door of the technocratic elite classroom: here the infrastructure gets subtle shape and aesthetic qualities, expressed in various ways of computer visualization, designer drawings and infographics. For publicly appearing to the unnamed observer, visualizations take away the promise: while seemingly incomprehensible mysterious ornaments, their accuracy makes them believe that they have an important external goal.

The look at the map of the infrastructure has a certain psychological effect: it seems to us that we have received permission to peek at the backstage power, perhaps even to the minds of the decision makers.

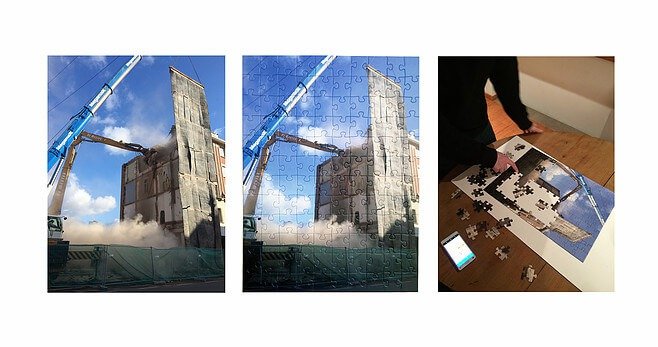

David Delruelle: Re(de)construction

However, I think that highly aesthetized visualization of infrastructure is perceived as a fetish. Separated from the context in which they are created and used, visualizations begin to promise something they will never be able to provide: engagement and participation in decision-making about the future. Infrastructure aesthetics is just a relic, a trace of sophisticated social networks and practices. It is not a window to the mind of the decision maker, but rather an enticing ritual, a trace of financial currents or a promise, as in reality their link with detailed plans is very fluid. According to von Hirschhausen, a lot of infrastructure plans and their implementation small, because the real power is concentrated in the social decision-makers and stakeholders setting, where the combined action according to needs. Infrastructure becomes meaningful and contributes to growth only when integrated into a social fabric. A detailed analysis of infrastructure visualization yields little value if it does not take into account their original context. Jacques Rancière seems to lose weight in the case of radically democratized aesthetic power in the case of infractions.

I think that these two elements, the invisibility of the infrastructure itself and the aesthetic expression of its visualizations, are closely interrelated as a discourse for a successful economic and civilization development. If an average person can see the inactivity of the infrastructure, failures, this is an important indicator of the political economy. As Edward observes, invisible, smooth running infrastructures are a luxury in a developed country, while infrastructure in developing countries is much more visible . The more visible the infrastructure (more precisely, their failures), the greater the likelihood that a single citizen has the durability of both political powers. Therefore, extreme Soviet infrastructure visibility, the difference deridiška sense, expressed long-standing inability to perform the functions assigned to it, was a clear sign of the collapse of the Soviet regime. Functionalist multi-storey residential buildings, Nubero Baltic countries, is a great infrastructure visibility illustration: Khrushchev initiated a cheap and fast modernization of the state, Paulo Josephsono words, "pražildė Eastern Europe, nupilkindama urban landscapes of poor quality concrete .

It is a permanent infrastructure failure and the catastrophic collapse of Chernobyl and Spitak earthquake in Soviet Armenia cases certainly discredited Soviet regime. The collapse of infrastructure continues to have a profound political impact even after the end of the Soviet Union: the collapse of Maxima's supermarket, killing 55 people in Riga in 2013, prompted residents of the three Baltic States to question the legitimacy of their experts and governments. I do not mention these examples to suggest that a political change is impossible without major disasters, but on the contrary, in order to show that a smoothly functioning infrastructure, along with its proliferation of fetishistic images, has something authoritarian referring to the fundamental social consensus and control used to preserve the status quo.

It seems that the poor functioning of the infrastructure reveals a comfortable myth about the allegedly centralized management of infrastructure; It seems to be a center for everything responsible for everything, an expert on everything. It is clear from the scarcity of this steady present and future illusion that government centralized public control is based only on a fragile agreement, a network of beliefs. Perhaps we should understand the interruptions and collapse of infrastructure as the momentum of a very painfully won freedom that opens the way for new political actors and a new future.

Credits: Eglė Rindzevičiūtė

Congratulations @allabout! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPQuite interesting! Keep it up!

If you have time read this: https://platincoin.com/en/8504301930

That's too much for me to read it all, but it's interesting of what the future may hold and how things were expected to be in the future from our past.