There's a movie called Arrival playing in theaters right now. It's about a translator interacting with aliens who have landed on Earth so that humanity can understand the alien language and why they have come.

Arrival is a beautiful and thoughtful film, and the aliens look almost exactly how I would have designed them if I were trying to create realistic aliens who look nothing like humans. I'm sure the designers followed the same line of thought as myself: something as good as hands or better are the key. Opposable thumbs are our ace.

But when you look at animal intelligence on earth, some of the smartest animals are some of the most lacking in such physical tools. Elephants, chimps, and octopuses are no big surprise. But what should we make of dolphins, parrots, and pigs? These animals are basically just working with their mouths. I know from experience that parrots can make pretty great use of their tongues. I was surprised to read that pigs "root around for difficult food sources, requiring a dexterity of the snout not unlike the handiness of a monkey."

Still, that's nothing on hands or tentacles. So I burrowed into the intelligence of these animals, and found, unsurprisingly, another aspect to which humans' great intelligence is regularly attributed:

"Dr. Byrne attributes pig intelligence to the same evolutionary pressures that prompted cleverness in primates: social life and food. Wild pigs live in long-term social groups, keeping track of one another as individuals, the better to protect against predation." - Natalie Angier, NY Times

Almost our entire perception of intelligence centers around individual capacity for social interaction. (That is, we largely disregard hive intelligence, even though in this aspect ants are not only more successful than humans, but one of the smartest species on Earth.) One of the most famous tests of animal intelligence, the mirror test, requires that an animal recognize their own self in a mirror and be able to respond to that understanding. Researchers also look for communication abilities, emotional empathy, tool use, and puzzle-solving potential. But the key seems to often come down to language, which humans are absolutely pathetic at understanding -- so much so that they end up teaching gorillas sign language and parrots human languages, rather than go through the difficulty of learning the animals' languages. We've been living with animals for millennia, but we still have only a rudimentary understanding of even cat meows. Meanwhile, each baby cat or dog manages to learn key human words from scratch.

With such pathetic progress with species on our own planet, how could we possibly learn an alien language? Arrival has another bright idea in how the protagonist goes about learning the alien language and the way that language works: both require thinking entirely outside the box, to the extent that only one person in the whole world figures it out. In other words, human beings are really, really bad at thinking creatively to understand communication in other species.

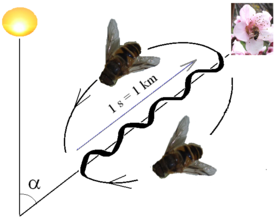

We expect to find individual words conveyed through vocalizations or, if we're thinking particularly creatively, through consistent visual signals. Yet in recent years, we've come to realize that rats respond better to scent than visual or audio cues, that seemingly silent giraffes communicate through infrasonic sounds, that honeybees communicate through pheromones and dances, and that most animals perceive color in a completely different way than we do. Trying to figure out even the means most effective for a specific species to communicate is like trying to figure out that 100 trillion neutrinos are passing through our bodies every second. We often lack the tools, and we certainly often lack the creative effort to even imagine what tools we need.

Until we manage to understand a gorilla on its own terms, it seems pretty likely that if aliens did visit, we'd spend most of the time trying to teach them English or Chinese. It may seem strange to sincerely say that human beings are arrogant, but the approach we often take to animal communication and intelligence is strikingly similar to the approach conquerors throughout human history have taken to the people they conquer: the slaves learn the masters' language, not the other way around.

In a nutshell, when we approach a parrot, we say, "YOU learn it." We go crazy about how clever we are to teach a parrot how to greet us in our language, but we can rarely understand nor imitate their version of hello -- even though the fact that they understand the concept implies they probably have or will invent their own version. There's also too little consideration of communal pockets of animals, because true language is something formed by communities. A baby parrot or pig probably lacks anything like a language, just as a baby human does. But what of areas in the world where a certain species has lived for generations?

Humans are so arrogant that they simply assume animal language. For example, many people think parrots are dancing when they bob their heads, but this is usually a sign of aggression. They don't even stop to ask, "What does that mean?" a lot of the time. We ask more of animals than we give. Compared to even the ability of less intelligent animals like ducks to understand human verbal cues (I have owned ducks I taught some commands), humans are positively stupid in their understanding of other animals.

Koko's sign language ability implies wild gorilla communities probably have a very complex language of their own, but if it's subtle and not in the form we expect, very few researchers can manage to work it out. For example, primatologist Dr. Dian Fossey was a leader in the field who studied gorillas for 18 years, yet only managed to identify 17 extremely basic communication sounds and signals. A research assistant of hers, Ian Redmond, agrees that "they clearly have the capacity to understand language and it would be surprising if that was there and there was no natural use of it.” Actually, it's almost inconceivable that a gorilla like Koko has the mental capacity to learn over 1,000 different sign language signals but would develop less than 20 very basic communications among its own kind over generations. After all, this makes it clear that Koko is both capable of conceiving of all of the meanings behind those signs, and also has the desire to convey them.

Yes, our language is by far the most complex, but other animals aren't all that stupid. But maybe there's some guilt involved here, too: if elephants perform amazingly well on cooperative puzzles, how can we justify keeping them alone or even in pairs in cramped quarters? If pigs are smarter than dogs, how do we reconcile our disgust at dog abuse and our horrifying factory farm treatment of pigs? If we're not the brightest in every possible way, how can we excuse using the entire planet like our species' personal possession? And moreover, what does this imply about our treatment of our own fellow human beings?

When I taught English in Japan, I found that intelligence was not the key factor in learning language. It was attitude. People who said, "I can't do that," "I'm embarrassed," "I'm too old," or, "It's just too hard for me," were unable to learn very well. Kids and adults who went into it with an open and eager mind learned fast, even if they made mistakes along the way. Animals come to us with this openness, which is surely part of why an animal like the famous African grey parrot Alex "was said to have understood the turn-taking of communication and sometimes the syntax used in language. He called an apple a 'banerry,' which a linguist friend of Pepperberg's thought to be a combination of 'banana' and 'cherry', two fruits he was more familiar with," and yet no human has been reported to even convey "banana" to any animal in a non-human language. We simply assume they lack the ability and leave off there.

If aliens show up, maybe we should send a humble gorilla to learn and interpret their language.

Image Credits

Octopus

Pig

Bee Dance

African Grey

Elephants

Gorilla

Thanks for posting this. If we are to explore space - which is something I hope - we need to further our understanding and learn how to communicate with the fellow other Earthlings we are already amongst and bring them along.

Very interesting article. I think humans are very limited in their approach to what language is. Communication is more than just language - most human communication is non-verbal (facial expressions, body postures, hand gestures, general energy). Animals are similar in that regard, just with less sounds and more non-verbal bits.

Animals understand human communication. If you have a dog - that dog knows when you're sad or happy and tends to have empathy.

It may also be worth looking into telepathic communication. Certain aboriginal tribes were reportedly able to communicate without sounds and words. Then again that's not something that science could easily prove. How do you communicate modern science with someone who can't and doesn't intend to speak your language?

I think if aliens do arrive like in the film Arrival - then humans aren't ready for it yet. We're too primitive and hostile to be tolerant and learn their language. So we'd probably scare them off or attack them. Hence why they're probably not here.

We apply the opposable thumbs theory probably because it's something we've realized applies to us and declared, this is a mark of superiority. Aliens might teach us someday that it's not that great of an evolutionary feat.

That's probably true as well. Hell, even tentacles seem a lot more useful to me. Octopuses are famously effective escape artists and object manipulators. I didn't branch out to this here, but I think the way we treat animals greatly affects the way we treat one another. As long as we can justify not extending empathy to thinking, feeling beings, we can justify hurting each other.

Absolutely excellent article. Being a science fiction writer, I often just take a shortcut with deus-ex-machina devices like universal nanite translators or somesuch, but when I sit down and think about how communication actually happens (like I've been doing for a story I'm writing) and what it would be like to try communicating with another species of intelligent beings, it's incredible how difficult it is. I have to strain my brain to think up ways that one could understand a completely alien vocabulary, and I love that you've drawn a parallel between that kind of situation to how we try (pitifully) to communicate with fairly intelligent creatures on our own planet.

Very thoughtful stuff.

thx bro

Excellent post! Following..

I think humans, as species are more capable, is some areas and less capable in other. Humans, for example, are absolutely incapable of flying while most birds and many insects can do this naturally. Perhaps the ability to understand alien language is not one of the strong sides of human intellect. That doesn’t mean that human won’t be able to communicate with alien species. This is just mean that alien species that are more apt of understanding alien to them language would learn human languages and thus establish communication. Once such communication will be established, humans will learn from them their methods of pinpointing the alien syntax, grammar, semantics and maybe some other new alien language attributes. At least, I am hopeful.

saw the film the other night - sure wasn't what i was expecting!

a perceptive reflection on modes of communication. I'm sure your experience of teaching English to unwilling minds provided some insight as well as inspiration :)