III. 노동Labor

11.. 우리 몸체의 노동(애니멀 라보란스) 및 우리 손들의 작업(호모 파베르)"The Labour of Our Body and the Work of Our Hands"

내가 제안한 노동과 작업의 구별은 생소하다... 정치적인 생각의 전근대적인 전통 안에서건 또는 근대적인 노동이론의 큰 몸체 안에서건 나의 구별을 지원하는 것은 찾기 힘들다. 역사적인 증거가 없음에도 하지만 가즌 유럽언어들은... 동일한 활동을 표현하는... 두 개의 어원학적으로 관계없는 낱말들을 담고 있다(156)The distinction between labor and work which I propose is unusual. The phenomenal evidence in its favor is too striking to be ignored, and yet historically it is a fact that apart from a few scattered remarks, which moreover were never developed even in the theories of their authors, there is hardly anything in either the premodern tradition of political thought or in the large body of modern labor theories to support it. Against this scarcity of historical evidence, however, stands one very articulate and obstinate testimony, namely, the simple fact that every European language, ancient and modern, contains two etymologically unrelated words for what we have to come to think of as the same activity, and retains them in the face of their persistent synonymous usage.

로크의 <작업하는 손들>과 <노동하는 어떤 몸체> 사이의 구별은, <케이로테크네스(장인, 독일어의 한트베르커)>와 <토 소마티 에르가제스타이(주인의 생명삶의 너쎄시티(필수욕구됨; 먹고사니즘)들을 위해서 자체의 몸체들로 대신하는 노예들과 길들여진 동물들처럼 스스로들의 몸체들로써 작업하는)> 사이의 고대 그리스적인 구별을 회상하게 한다. 고대 그리스에서도 이미 노동과 작업은 동일하게 여겨졌다. 왜냐하면 이때 쓰인 낱말은 포네인(노동)이 아니라 에르가세스타이(작업)이기 때문이다(156~ 157)Thus, Locke's distinction between working hands and a laboring body is somewhat reminiscent of the ancient Greek distinction between the cheirotechnes, the craftsman, to whom the German Handwerker corresponds, and those who, like "slaves and tame animals with their bodies minister to the necessities of life," or in the Greek idiom, to somati ergazesthai, work with their bodies(yet even here, labor and work are already treated as identical, since the word used is not ponein [labor] but ergazesthai [work]).

노동에 대한 경멸은 기원적으로 정치적인 활동들 말고는 모든 것을 삼가야함(스콜레)에 대한 강요 및 시민들에게 폴리스의 생명삶을 위한 시간을 더늘리라는 요구들에 의해 확산되었고... 급기야는 노력을 요구하는 가즌거시기들로까지 확대되었다(157)Contempt for laboring, originally arising out of a passionate striving for freedom from necessity and a no less passionate impatience with every effort that left no trace, no monument, no great work worthy of remembrance, spread with the increasing demands of polis life upon the time of the citizens and its insistence on their abstention(skhole) from all but political activities, until it covered everything that demanded an effort.

원주7. 생존을 위한 활동은 18세기에도 여전히 노예의 일로 규정되었다(159)Politics 1258b35 ff. For Aristotle's discussion about admission of banausoi to citizenship see Politics iii. 5. His theory corresponds closely to reality: it is estimated that up to 80 per cent of free labor, work, and commerce consisted of non-citizens, either "strangers"(katoikountes and metoikoi) or emancipated slaves who advanced into these classes(see Fritz Heichelheim, Wirtsckaftsgeschichte des Altertums [1938], I, 398 ff.). Jacob Burckhardt, who in his Griechische Kulturgeschichte(Vol. II, sees. 6 and 8) relates Greek current opinion of who does and who does not belong to the class of banausoi, also notices that we do not know of any treatise about sculpture. In view of the many essays on music and poetry, this probably is no more an accident of tradition than the fact that we know so many stories about the great feeling of superiority and even arrogance among the famous painters which are not matched by anecdotes about sculptors. This estimate of painters and sculptors survived many centuries. It is still found in the Renaissance, where sculpturing is counted among the servile arts whereas painting takes up a middle position between liberal and servile arts(see Otto Neurath, "Beitrage zur Geschichte der Opera Servilia," Archivfur Sozialtvissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, Vol. XLI, No. 2 [1915]).. That Greek public opinion in the city-states judged occupations according to the effort required and the time consumed is supported by a remark of Aristotle about the life of shepherds: "There are great differences in human ways of life. The laziest are shepherds; for they get their food without labor [poms] from tame animals and have leisure [skhohzousin]"(Politics 1256a3O ff.). It is interesting that Aristotle, probably following current opinion, here mentions laziness(aereia) together with, and somehow as a condition for, skhole, abstention from certain activities which is the condition for a political life. Generally, the modern reader must be aware that aergia and skhole are not the same. Laziness had the same connotations it has for us, and a life of skhole was not considered to be a lazy life. The equation, however, of skhole and idleness is characteristic of a development within the polis. Thus Xenophon reports that Socrates was accused of having quoted Hesiod's line: "work is no disgrace, but laziness [aergia] is a disgrace." The accusation meant that Socrates had instilled in his pupils a slavish spirit(Memorabilia i. 2. 56). Historically, it is important to keep in mind the distinction between the contempt of the Greek city-states for all non-political occupations which arose out of the enormous demands upon the time and energy of the citizens, and the earlier, more original, and more general contempt for activities which serve only to sustain life— ad vitae sustentationem as the opera servilia are still defined in the eighteenth century. In the world of Homer, Paris and Odysseus help in the building of their houses, Nausicaa herself washes the linen of her brothers, etc. All this belongs to the self-sufficiency of the Homeric hero, to his independence and the autonomic supremacy of his person. No work is sordid if it means greater independence; the selfsame activity might well be a sign of slavishness if not personal independence but sheer survival is at stake, if it is not an expression of sovereignty but of subjection to necessity. The different estimate of craftsmanship in Homer is of course well known. But its actual meaning is beautifully presented in a recent essay by Richard Harder, Eigenart derGriechen(1949).

인간활동들에 대한 고대인들의 견적은, 욕구들에 의해서 필수욕구적이 되는 우리 몸체의 노동은 노예적이라는 확신에 근거하고 있다. 그래서 비록 노동하기는 아니지만, 생명삶의 너쎄시티(필수욕구됨; 먹고사니즘)들을 제공하기 위해 떠맡겨지는 직업들은 모두 노동의 신분지위에 동화되었다... 생명삶의 유지를 위한 욕구들에 용역하는 모든 직업들의 노예적 본성 때문에 노예들을 포제쎤하는 것이 필요하다고 생각되었다. 정확하게 노예제도를 방어하고 떳떳케한 것은 바로 이 논리였다. 노동한다는 것은 너쎄시티(필수욕구됨; 먹고사니즘)에 의해 노예화되는 것을 의미했다. 그리고 이러한 노예화는 인간생명삶의 조건상태들 안에 내재된 것이었다. 생명삶의 너쎄시티(필수욕구됨; 먹고사니즘)들에 의해 도미네이션되기 때문에, 너쎄시티(필수욕구됨; 먹고사니즘)에 예속된 노예들을 강제력에 의해서 도미네이션하기를 통해서만 사람들은 오직 스스로들의 프리덤을 승리해낼 수 있다. 노예로의 퇴행이라는 것은 숙명의 어떤 일격이었고 죽음보다 더 나쁜 어떤 숙명이었다. 왜냐하면 그것은 사람을 길들여진 어떤 동물을 닮은 어떤거시기로 메타모르포시스시키는 것이기 때문이다(160)We shall see later that, quite apart from their contempt for labor, the Greeks had reasons of their own to mistrust the craftsman, or rather, the homo faber mentality. This mistrust, however, is true only of certain periods, whereas all ancient estimates of human activities, including those which, like Hesiod, supposedly praise labor, rest on the conviction that the labor of our body which is necessitated by its needs is slavish. Hence, occupations which did not consist in laboring, yet were undertaken not for their own sake but in order to provide the necessities of life, were assimilated to the status of labor, and this explains changes and variations in their estimation and classification at different periods and in different places. The opinion that labor and work were despised in antiquity because only slaves were engaged in them is a prejudice of modern historians. The ancients reasoned the other way around and felt it necessary to possess slaves because of the slavish nature of all occupations that served the needs for the maintenance of life. It was precisely on these grounds that the institution of slavery was defended and justified. To labor meant to be enslaved by necessity, and this enslavement was inherent in the conditions of human life. Because men were dominated by the necessities of life, they could win their freedom only through the domination of those whom they subjected to necessity by force. The slave's degradation was a blow of fate and a fate worse than death, because it carried with it a metamorphosis of man into something akin to a tame animal. A change in a slave's status, therefore, such as manumission by his master or a change in general political circumstance that elevated certain occupations to public relevance, automatically entailed a change in the slave's "nature."

노예제도는 노동을 생명삶의 조건상태들로부터 배제하기 위한 어떤 장치였다(161)The institution of slavery in antiquity, though not in later times, was not a device for cheap labor or an instrument of exploitation for profit but rather the attempt to exclude labor from the conditions of man's life.

원주10. 에우리피데스는... 노예라는 것은 모든 것을 밥통의 관점에서 바라본다고 말했다(161)It is in this sense that Euripides calls all slaves "bad": they see everything from the viewpoint of the stomach(Suppiementum Eutipideum, ed. Arnim, frag. 49, no. 2).

고전고대에 노동과 작업 사이의 구별이 무시되었다는 것은 놀랍지 않다(162)It is not surprising that the distinction between labor and work was ignored in classical antiquity. 사적인 하우스홀드와 공적인 정치적인 권역 사이의 차이, 하우스홀드의 수용된이(노예)와 하우스홀드 우두머리(시민) 사이의 차이, 프라이버시(사적임) 안에 감춰져야할 활동들(노동, 작업)과 보여지고, 들려지고, 기억되어져야할 값어치있는 활동들(행동, 발언) 사이의 차이가 모든 다른 차이들을 무색하게 만들었고, 결국 오직 하나의 평가기준만이 남게 되었다: 시간과 노력의 더커다란 총량을 사적으로 썼는가, 아니면 공적으로 썼는가?(162)The differentiation between the private household and the public political realm, between the household inmate who was a slave and the household head who was a citizen, between activities which should be hidden in privacy and those which were worth being seen, heard, and remembered, overshadowed and predetermined all other distinctions until only one criterion was left: is the greater amount of time and effort spent in private or in public? 직업은 사적인 거시기를 위한 배려인가, 아니면 공적인 거시기를 위한 배려인가?(162)is the occupation motivated by cura privati negotii or cura rei publicae, care for private or for public business? 심지어는 활동들 사이에 최소한 구별되었던, 이러한 구별마저도, 정치적인 이론의 일어남과더불어써, 관조를 활동의 모든 종류들에 대립시켜버림에 의해, 사라졌다(162)With the rise of political theory, the philosophers overruled even these distinctions, which had at least distinguished between activities, by opposing contemplation to all kinds of activity alike. (이제는) 심지어는 정치적인 활동마저도 너쎄시티(필수욕구됨; 먹고사니즘)의 신분지위를 향해 평준화되어졌고, 너쎄시티(필수욕구됨; 먹고사니즘)이 따라서 비타 악티바 속의 모든 분절들의 공통분모가 되었다(162)With them, even political activity was leveled to the rank of necessity, which henceforth became the common denominator of all articulations within the vita activa. Nor can we reasonably expect any help from Christian political thought, which accepted the philosophers' distinction, refined it, and, religion being for the many and philosophy only for the few, gave it general validity, binding for all men.

근대는 모든 전통들을 뒤집어 버렸다. 근대는 행동과 관조 사이의 전통적인 신분지위를 비타 악티바 속의 전통적인 위계서열에 불과한 것으로 뒤집어 버렸다. 노동을 모든 가치들의 원천으로 영광스럽게 만들었고, 근대는 전통적으로 이성적인 동물이 붙들고 있었던 지위로까지 노동하는 동물을 신분상승시켰다. 이러한 근대였음에도 놀랍게도 애니멀 라보란스(우리 몸체의 노동)와 호모 파베르(우리 손들의 작업)를 깨끗하게 구별하는 단일한 어떤 이론을 내놓지 못했다(162)It is surprising at first glance, however, that the modern age— with its reversal of all traditions, the traditional rank of action and contemplation no less than the traditional hierarchy within the vita activa itself, with its glorification of labor as the source of all values and its elevation of the animal laborans to the position traditionally held by the animal rationale— should not have brought forth a single theory in which animal laborans and homo faber, "the labour of our body and the work of our hands," are clearly distinguished. 그대신에 첫째로 생산적인 노동과 비생산적인 노동 사이의 구별, 나중에는 숙련된 노동과 미숙련노동 사이의 구별, 마지막으로 육체노동과 지성의 노동 사이의 구별을 근대는 발견했다(162)Instead, we find first the distinction between productive and unproductive labor, then somewhat later the differentiation between skilled and unskilled work, and, finally, outranking both because seemingly of more elementary significance, the division of all activities into manual and intellectual labor. Of the three, however, only the distinction between productive and unproductive labor goes to the heart of the matter, and it is no accident that the two greatest theorists in the field, Adam Smith and Karl Marx, based the whole structure of their argument upon it. The very reason for the elevation of labor in the modern age was its "productivity," and 하나님이 아니라 노동이 사람을 창조했고 또는 이성이 아니라 노동이 사람을 다른 동물들로부터 구별한다는 불경스럽게 보이는 맑스의 개념 오직 근대가 전일적으로 합의한 바인 어떤 사실을 래디컬하고 공통-지속적으로 형태식화한 것일 따름이다(163)the seemingly blasphemous notion of Marx that labor(and not God) created man or that labor(and not reason) distinguished man from the other animals was only the most radical and consistent formulation of something upon which the whole modern age was agreed.

원주14. "The creation of man through human labor" was one of the most persistent ideas of Marx since his youth. It can be found in many variations in the Jugendschriften(where in the "Kritik der Hegelschen Dialektik" he credits Hegel with it).(See Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe, Part I, Vol. 5 [Berlin, 1932], pp. 156 and 167.) That Marx actually meant to replace the traditional definition of man as an animal rationale by defining him as an animal laborans is manifest in the context. The theory is strengthened by a sentence from the Deutsche Ideologic which was later deleted: "Der erste geschichtliche Akt dieser Individuen, wodurch sie sich von den Tieren unterscheiden, ist nicht, dass sie denken, sondern, dass sie anfangen ihre Lebensmittel zu produzieren"(ibid., p. 568). Similar formulations occur in the "Okonomisch-philosophische A4anuskripte"(ibid., p. 125), and in "Die heilige Familie"(ibid., p. 189). Engels used similar formulations many times, for instance in the Preface of 1884 to Ursprung der Familie or in the newspaper article of 1876, "Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man"(see Marx and Engels, Selected works [London, 1950], Vol. II). 노동이 사람을 동물로부터 구별한다고 처음 주장한이는 맑스가 아니라 흄이다(163)It seems that Hume, and not Marx, was the first to insist that labor distinguishes man from animal(Adriano Tilgher, Homo faber [1929]; English ed.: work: What It Has Meant to Men through the Ages [1930]). As labor does not play any significant role in Hume's philosophy, this is of historical interest only; to him, this characteristic did not make human life more productive, but only harsher and more painful than animal life. It is, however, interesting in this context to note with what care Hume repeatedly insisted that neither thinking nor reasoning distinguishes man from animal and that the behavior of beasts demonstrates that they are capable of both.

Moreover, both Smith and Marx were in agreement with modern public opinion when they despised unproductive labor as parasitical, actually a kind of perversion of labor, as though nothing were worthy of this name which did not enrich the world. Marx certainly shared Smith's contempt for the "menial servants" who like "idle guests... leave nothing behind them in return for their consumption."16 Yet it was precisely these menial servants, these household inmates, oiketai or familiares, laboring for sheer subsistence and needed for effortless consumption rather than for production, whom all ages prior to the modern had in mind when they identified the laboring condition with slavery. What they left behind them in return for their consumption was nothing more or less than their masters' freedom or, in modern language, their masters' potential productivity.

In other words, 생산적인 노동과 비생산적인 노동 사이의 구별은... 작업과 노동 사이의 보다 근본기초적인 구별을 담고 있다(164)the distinction between productive and unproductive labor contains, albeit in a prejudicial manner, the more fundamental distinction between work and labor.16 It is indeed the mark of all laboring that it leaves nothing behind, that the result of its effort is almost as quickly consumed as the effort is spent. And yet this effort, despite its futility, is born of a great urgency and motivated by a more powerful drive than anything else, because life itself depends upon it. 근대는 일반적으로 그리고 맑스는 파티큘라하게, 모든 노동을 작업으로 간주한 나머지, 애니멀 라보란스라고 불러야 할 것을 호모 파베르라고 발언했다(164)The modern age in general and Karl Marx in particular, overwhelmed, as it were, by the unprecedented actual productivity of Western mankind, had an almost irresistible tendency to look upon all labor as work and to speak of the animal laborans in terms much more fitting for homo faber, hoping all the time that only one more step was needed to eliminate labor and necessity altogether.17

No doubt 행동현실적으로 노동을 숨겨진 (사적인 권역)으로부터 꺼내와서, 노동을 조직화하고 '분할'하는 공적인 권역 안을향해 끌어들이는 역사적인 개발이 이루어졌다(165)the actual historical development that brought labor out of hiding and into the public realm, where it could be organized and "divided,"18 constituted a powerful argument in the development of these theories. Yet an even more significant fact in this respect, already sensed by the classical economists and clearly discovered and articulated by Karl Marx, is that the laboring activity itself, regardless of historical circumstances and independent of its location in the private or the public realm, possesses indeed a "productivity" of its own, no matter how futile and non-durable its products may be. This productivity does not lie in any of labor's products but in the human "power," whose strength is not exhausted when it has produced the means of its own subsistence and survival but is capable of producing a "surplus," that is, more than is necessary for its own "reproduction." It is because not labor itself but the surplus of human "labor power"(Arbeitskraft) explains labor's productivity that Marx's introduction of this term, as Engels rightly remarked, constituted the most original and revolutionary element of his whole system.19 새로운 오브젝트들을 인간의 인공체에 더하는 작업의 생산성과 다르게, 노동력의 생산성은 오브젝트들을 오직 우발적으로 생산하고, 1차적으로 자체의 재생산의 수단자산에만 관심을 갖는다(165)Unlike the productivity of work, which adds new objects to the human artifice, the productivity of labor power produces objects only incidentally and is primarily concerned with the means of its own reproduction; since its power is not exhausted when its own reproduction has been secured, it can be used for the reproduction of more than one life process, but 노동력은 생명삶 말고는 결코 아무것도 생산하지 못한다(166)it never "produces" anything but life.20 Through violent oppression in a slave society or exploitation in the capitalist society of Marx's own time, it can be channeled in such a way that the labor of some suffices for the life of all.

The distinction between productive and unproductive labor is due to the physiocrats, who distinguished between producing, property-owning, and sterile classes. Since they held that the original source of all productivity lies in the natural forces of the earth, their standard for productivity was related to the creation of new objects and not to the needs and wants of men. Thus, the Marquis de iVIirabeau, father of the famous orator, calls sterile "la classe d'ouvriers dont les travaux, quoique necessaires aux besoins des hommes et utiles a la societe, ne sont pas neanmoins productifs" and illustrates his distinction between sterile and productive work by comparing it to the difference between cutting a stone and producing it(see Jean Dautry, "La notion de travail chez Saint-Simon et Fourier," Journal de psychologie normale et fathologique, Vol. LII, No. 1 [January-March, 1955]).

This hope accompanied Marx from beginning to end. We find it already in the Deutsche Ideologie: "Es handelt sich nicht darum die Arbeit zu befreien, sondern sie aufzuheben"(Gesamtausgabe, Part I, Vol. 3, p. 185) and many decades later in the third volume of Das Kapital, ch. 48: "Das Reich der Freiheit beginnt in der Tat erst da, wo das Arbeiten... aufhort"(Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe, Part II [Zurich, 1933], p. 873).

In his Introduction to the second book of the wealth of Nations(Everyman's ed., I, 241 ff.), Adam Smith emphasizes that productivity is due to the division of labor rather than to labor itself.

See Engels' Introduction to Marx's "Wage, Labour and Capital"(in Marx and Engels, Selected works [London, 1950], I, 384), where Marx had introduced the new term with a certain emphasis.

Marx stressed always, and especially in his youth, that the chief function of labor was the "production of life" and therefore saw labor together with procreation(see Deutsche Ideologic, p. 19; also "Wage, Labour and Capital," p. 77).

From 근대의 전일적인 관점인, 이러한 순수하게 사회적인 관점은... 맑스에게서 가장 일관되고 커다란 표현을 얻었다(166)this purely social viewpoint, which is the viewpoint of the whole modem age but which received its most coherent and greatest expression in Marx's work, all laboring is "productive," and the earlier distinction between the performance of "menial tasks" that leave no trace and the production of things durable enough to be accumulated loses its validity. The social viewpoint is identical, as we saw before, with an interpretation that takes nothing into account but the life process of mankind, and within its frame of reference all things become objects of consumption. 완전하게 "사회화된 인류" 속에서 노동과 작업 사이의 구별은 완전하게 사라지고, 모든 작업은 노동이 되고 말 것이다(167)Within a completely "socialized mankind," whose sole purpose would be the entertaining of the life process— and this is the unfortunately quite unutopian ideal that guides Marx's theories21— the distinction between labor and work would have completely disappeared; all work would have become labor because all things would be understood, not in their worldly, objective quality, but as results of living labor power and functions of the life process.22

The terms vergesellschafteter Mensch or gesellschaftliche Menschheit were frequently used by Marx to indicate the goal of socialism(see, for instance, the third volume of Das Kapital, p. 873, and the tenth of the "Theses on Feuerbach": "The standpoint of the old materialism is 'civil' society; the standpoint of the new is human society, or socialized humanity"(Selected works, II, 367]). It consisted in the elimination of the gap between the individual and social existence of man, so that man "in his most individual being would be at the same time a social being [a Gemeintaesen]"(Jugendschriften, p. 113). Marx frequently calls this social nature of man his Gattungstoesen, his being a member of the species, and the famous Marxian "self-alienation" is first of all man's alienation from being a Gattungsivesen(ibid., p. 89: "Eine unmittelbare Konsequenz davon, dass der Mensch dem Produkt seiner Arbeit, seiner Lebenstatigkeit, seinem Gattungswesen entfremdet ist, ist die Entfremdung des Menschen von dem Menschen"). The ideal society is a state of affairs where all human activities derive as naturally from human "nature" as the secretion of wax by bees for making the honeycomb; to live and to labor for life will have become one and the same, and life will no longer "begin for [the laborer] where [the activity of laboring] ceases"("Wage, Labour and Capital," p. 77).

Marx's original charge against capitalist society was not merely its transformation of all objects into commodities, but that "the laborer behaves toward the product of his labor as to an alien object"("dass der Arbeiter zum Produkt seiner Arbeit als einem fremden Gegenstand sich verhalt" [Jugendschriften, p. 83])— in other words, that the things of the world, once they have been produced by men, are to an extent independent of, "alien" to, human life.

It is interesting to note that the distinctions between skilled and unskilled and between intellectual and manual work play no role in either classical political economy or in Marx's work. Compared with the productivity of labor, they are indeed of secondary importance. Every activity requires a certain amount of skill, the activity of cleaning and cooking no less than the writing of a book or the building of a house. The distinction does not apply to different activities but notes only certain stages and qualities within each of them. It could acquire a certain importance through the modem division of labor, where tasks formerly assigned to the young and inexperienced were frozen into lifelong occupations. But this consequence of the division of labor, where one activity is divided into so many minute parts that each specialized performer needs but a minimum of skill, tends to abolish skilled labor altogether, as Marx rightly predicted. Its result is that what is bought and sold in the labor market is not individual skill but "labor power," of which each living human being should possess approximately the same amount. Moreover, since unskilled work is a contradiction in terms, the distinction itself is valid only for the laboring activity, and the attempt to use it as a major frame of reference already indicates that the distinction between labor and work has been abandoned in favor of labor.

Quite different is the case of the more popular category of manual and intellectual work. Here, the underlying tie between the laborer of the hand and the laborer of the head is again the laboring process, in one case performed by the head, in the other by some other part of the body. thinking, however, which is presumably the activity of the head, though it is in some way like laboring— also a process which probably comes to an end only with life itself— is even less "productive" than labor; if labor leaves no permanent trace, thinking leaves nothing tangible at all. By itself, thinking never materializes into any objects. Whenever the intellectual worker wishes to manifest his thoughts, he must use his hands and acquire manual skills just like any other worker. In other words, thinking and working are two different activities which never quite coincide; the thinker who wants the world to know the "content" of his thoughts must first of all stop thinking and remember his thoughts. Remembrance in this, as in all other cases, prepares the intangible and the futile for their eventual materialization; 기억은 작업과정의 시작이다(168)it is the beginning of the work process, and like the craftsman's consideration of the model which will guide his work, its most immaterial stage. The work itself then always requires some material upon which it will be performed and which through fabrication, 호모 파베르의 활동은 세계있음의 어떤 오브젝트로 (기억을) 트랜스포메이션시킨다(168)the activity of homo faber, will be transformed into a worldly object. 지성의 작업의 특별한 작업성질은 (다른 작업과 마찬가지로) "우리의 손들의 작업"이라는 점이다(168)The specific work quality of intellectual work is no less due to the "work of our hands" than any other kind of work.

It seems plausible and is indeed quite common to connect and justify the modern distinction between intellectual and manual labor with 아르스 리베랄리스(리버럴 아트들)와 아르스 세르빌리스(서빌 아트들) 사이의 구별은... 지성의 더높은 등급정도도 아니고... 두뇌로 하는 작업하는 '자유로운 예술가'와 손을 쓰는 '천한 상인' 사이의 구별도 아니다(168)the ancient distinction between "liberal" and "servile arts." Yet the distinguishing mark between liberal and servile arts is not at all "a higher degree of intelligence," or that the "liberal artist" works with his brain and the "sordid tradesman" with his hands. 고대의 평가기준은 1차적으로 정치적이다(168)The ancient criterion is primarily political. 정치가들의 버츄인 신중한 판단의 역량인 프루덴티아를 갖는 직업들이나, 그리고 공적인 적합성(인간에게 효용있는)의 전문가들은... 자유롭다(169)Occupations involving prudentia, the capacity for prudent judgment which is the virtue of statesmen, and professions of public relevance(ad hominum utilitatem)™ such as architecture, medicine, and agriculture,24 are liberal. (둘째로) 모든 교역들, 어떤 목수의 거래와 다를 바 없는 어떤 글씨의 거래는, 어엿한 시민에게는 어울리지 않는, "천한" 것이다(169)All trades, the trade of a scribe no less than that of a carpenter, are "sordid," unbecoming for a full-fledged citizen, and (천한것들 가운데) 가장 최악은 가장 쓸모있다고 여기는 것들, '생선장사, 백정, 요리사, 새장수 그리고 어부들"이다(169)the worst are those we would deem most useful, such as "fishmongers, butchers, cooks, poulterers and fishermen."25 But not even these are necessarily sheer laboring. There is still 셋째 범주분류는 수고와 노력 자체가 돈을 받는다. 그리고 이 경우 '바로 그 임금이 노예의 표시이다'(169)a third category where the toil and effort itself(the operae as distinguished from the opus, the mere activity as distinguished from the work) is paid, and in these cases "the very wage is a pledge of slavery."26

For convenience' sake, I shall follow Cicero's discussion of liberal and servile occupations in De officiis i. 50-54. The criteria of prudentia and utilitas or utilitas hominum are stated in pars. 151 and 155.(The translation of prudentia as "a higher degree of intelligence" by Walter Miller in the Loeb Classical Library edition seems to me to be misleading.)

The classification of agriculture among the liberal arts is, of course, specifically Roman. It is not due to any special "usefulness" of farming as we would understand it, but much rather related to the Roman idea oipatria, according to which the ager Romctnus and not only the city of Rome is the place occupied by the public realm.

It is this usefulness for sheer living which Cicero calls mediocris utilitas (par. 151) and eliminates from liberal arts. The translation again seems to me to miss the point; these are not "professions . .. from which no small benefit to society is derived," but occupations which, in clear opposition to those mentioned before, transcend the vulgar usefulness of consumer goods.

The distinction between manual and intellectual work, though its origin can be traced back to the Middle Ages,27 is modern and has two quite different causes, both of which, however, are equally characteristic of the general climate of the modern age. Since under modern conditions every occupation had to prove its "usefulness" for society at large, and since the usefulness of the intellectual occupations had become more than doubtful because of the modern glorification of labor, it was only natural that intellectuals, too, should desire to be counted among the working population. At the same time, however, and only in seeming contradiction to this development, the need and esteem of this society for certain "intellectual" performances rose to a degree unprecedented in our history except in the centuries of the decline of the Roman Empire. It may be well to remember in this context that throughout ancient history the "intellectual" services of the scribes, whether they served the needs of the public or the private realm, were performed by slaves and rated accordingly. Only the bureaucratization of the Roman Empire and the concomitant social and political rise of the Emperors brought a re-evaluation of "intellectual" services.28 In so far as the intellectual is indeed not a "worker"— who like all other workers, from the humblest craftsman to the greatest artist, is engaged in adding one more, if possible durable, thing to the human artifice— he resembles perhaps nobody so much as Adam Smith's "menial servant," although his function is less to keep the life process intact and provide for its regeneration than to care for the upkeep of the various gigantic bureaucratic machines whose processes consume their services and devour their products as quickly and mercilessly as the biological life process itself.29

The Romans deemed the difference between opus and operae to be so decisive that they had two different forms of contract, the locatio opens and the locatio operarum, of which the latter played an insignificant role because most laboring was done by slaves(see Edgar Loening, in Handivorterbuch der Staatswissenschaften [1890], I, 742 ff.).

The opera liberalia were identified with intellectual or rather spiritual work in the Middle Ages(see Otto Neurath, "Beitrage zur Geschichte der Opera Servilia," Archivfur Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolkik, Vol. XLI [1915], No. 2).

H. Wallon describes this process under the rule of Diocletian: "... les fonctions jadis serviles se trouverent anoblies, elevees au premier rang de Flstat. Cette haute consideration qui de Fempereur se re'pandait sur les premiers serviteurs du palais, sur les plus hauts dignitaires de 1'empire, descendait a tous les degres des fonctions publiques . .. ; le service public devint un office public." "Les charges les plus serviles, ... les noms que nous avons cites aux fonctions de l'esclavage, sont revetus de l'eclat qui rejaillit de la personne du prince"(Histoire de l'esclavage dans I'antiquite [1847], III, 126 and 131). Before this elevation of the services, the scribes had been classified with the watchmen of public buildings or even with the men who led the prize fighters down to the arena {ibid., p. 171). 지식인들의 신분상승이 관료통치의 수립과 일치한다는 것은 주목할 값어치가 있다(170)It seems noteworthy that the elevation of the "intellectuals" coincided with the establishment of a bureaucracy.

"The labour of some of the most respectable orders in the society is, like that of menial servants, unproductive of any value," says Adam Smith and ranks among them "the whole army and navy," the "servants of the public," and the liberal professions, such as "churchmen, lawyers, physicians, men of letters of all kinds." Their work, "like the declamation of the actors, the harangue of the orator, or the tune of the musician... perishes in the very instant of its production"(op. cit., I, 295-96). Obviously, Smith would not have had any difficulty classifying our "white-collar jobs."

● 써위까지가 3부 11장 우리 몸체의 노동(애니멀 라보란스) 및 우리 손들의 작업(호모 파베르)"The Labour of Our Body and the Work of Our Hands" 가운데서 나에게 다가온 글귀들입니다.아렌트는 이 11장 안에서, 주로 맑스 정치경제학의 핵심개념용어인 "노동"을 중심으로, 아렌트의 독특한 구별인 <애니멀 라보란스(레이버) vs 호모 파베르(워크)>를 비교검토합니다.* <포네인= 레이버= 우리 몸체의 노동= 애니멀 라보란스> vs <에르가제스타이= 워크= 우리 손들의 작업= 호모 파베르>1) 어원학적으로 어휘론적으로 훈고학적으로 <포네인(레이버) vs 에르가제스타이(워크)>라는 두 개념낱말의 다른 기원을 살핀 뒤,2) 고대 그리스 도시국가의 공적인 정치적인 권역(액트) 안에서, 포네인(레이버)= 에르가세스타이(워크)를 어떻게 가치평가되었었는지를 밝힙니다. 그리고 여기서 멈추게 아니라, 공적인 정치적인 권역 곧 비타 악티바마저도, (고대 그리스 정치철학자들 및 중세 그리스도교의 등장과 그 스콜라신학에 의해서) 비타 콘템플라티바(테오리아; 관조)의 일어남 때문에, 포네인/에르가제스타이와 동급평준화되어짐도 이야기합니다.3) 이러한 관조의 우뚝섬과 노동/작업/행동의 하향평준화는 중세 내내 유지되었는데, 마침내 근대에 와서 사회적인것들(국민경제학)의 일어남이 이러한 전통적인 위계서열을 뒤집어버리기는 했지만, 그러나 다른한편으로 근대에서도 <애니멀 라보란스와 호모 파베르의 동일시는 여전하다>고 아렌트는 지적합니다. 아렌트는 로크- 흄- 스미스- 프루동- 맑스로 이어지는 근대의 경제학 안에서의 노동 개념을 (맑스의 노동 개념을 중심으로) 살핍니다. 기억할만한 부분: 생산노동 vs 비생산노동, 숙련노동 vs 미숙련노동, 육체노동 vs 지성의 노동. 이런 새로 나타난 노동의 3개 범주분류들을 아렌트는 분석합니다. 이러한 3개의 분석들 가운데서 특히 3번째가 흥미롭습니다. 근대 국민경제학의 <육체노동 vs 지성의 노동>을 그것의 중세적인 구별에 해당하는 <아르스 리베랄리스 vs 아르스 세르빌리스>와 비교하고, 다시 고대의 <리버럴 오큐패이션 vs 소르디드(천한) 오큐패이션 vs 슬레이버리 오큐패이션>과 비교하는 부분입니다. 이미 앞에서도 여러차례 봐왔던 바에 따르자면, [인간의 조건상태(인간의 조건)]이라는 책 안에서, 아렌트의 생각의 촛점은 <비타 악티바(액션)를 되살리는 데>에 있습니다. 이 목적을 이뤄내려면, 첫째로, 고대 및 중세 정치철학자들의 비타 콘템플라티바(관조) 우월주의를 이겨내야 하고, 둘째로, 근대 정치경제학자들(특히 맑스)의 애니멀 라보란스= 호모 파베르 동일시 및 레이버의 신격화를 깨트려야 하고, 셋째로, 사회적인것들(국민경제)의 일어남 때문에 팽배해진 순응주의/생각하지않음/대중사회/다수자의 티란니/고독/소외 등등 탓에 위축되고 무기력해진 비타 악티바(정치적인것들)를 다시금 개발성숙시켜야 합니다.이러한 <비타 악티바 부활프로젝트>에 의해서 파헤쳐지고 점차 모습을 내보이기 시작하는 아렌트의 가치설계/ 개념설계/제도 및 정책설계의 제시를 따라가는 것은 나에게는 아주 어렵지만 설레는 일입니다.

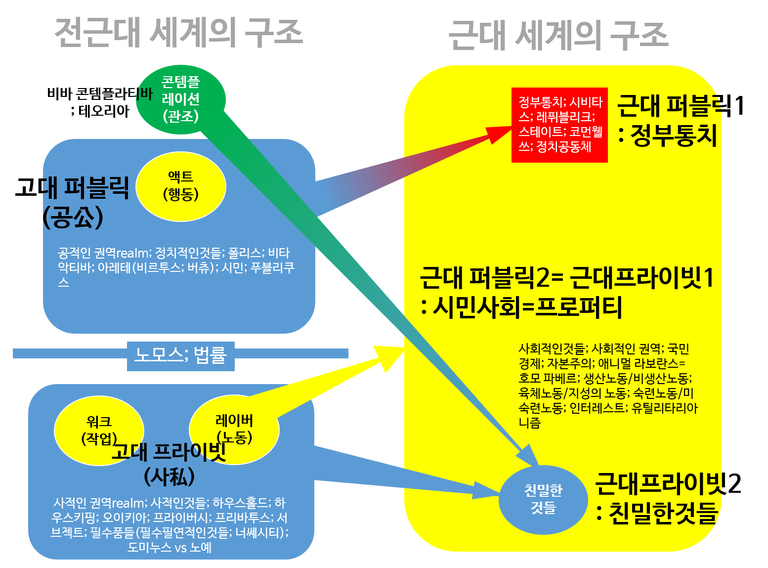

● 아마도 위 그림은 3/4분면 사회적 교환장을 해부한 것이라고 보면 될 듯 합니다. 그림을 보면 느끼겠지만, <전근대로부터 근대로의 그레이트 트랜스포메이션(대변형)>이 상당히 복잡합니다. 각각의 핵심요소들의 트랜스포지션(자리바꿈)이 아주 복잡합니다. 이러한 복잡한 트랜스포지션들 가운데 유독 가장 먼저 눈에 띄는 것은, <사회적인것들의 출현>입니다.이 사회적인 권역(국민경제)은 전근대문명 안에서는 없었던 것인데, 왜냐하면 전근대문명 안에서는 <하우스홀드; 패밀리>를 벗어나면 직접적으로 <폴리스; 푸블리쿠스>와 맞딱드렸기 때문입니다. 전근대에서 사람은 두가지 방식으로 추방당할 수 있는데, 하나는 패밀리로부터 추방당하는 것이고, 다른하나는 폴리스로부터 추방당하는 것입니다. 둘 다 곧 죽음이지요.그런데 근대에 오면, 사람들은 쉽게 안죽을 수 있게 됩니다. 하우스홀드(패밀리)로부터 추방당해도, 폴리스(정부통치)로부터 추방당해도, 사회가 있고, 친밀한것들이 있기 때문입니다. 아나키즘의 가능성이 여기에 있네요.이런 점(쉽게 안죽는다는 점)은 좋은데, 근대세계의 문제는 사회적인것들이 부르조아유다적인 자본주의 곧 <빈곤하고 불행한이들의 노동과 부르조아유다적인 사적인 프로퍼티 사이의 적대>에 의해서 세계가 관리운영된다는 데에 있습니다. 동일한 달-실재현실을 다른 측면으로 말하자면, 정부통치가 부르조아유다의 인터레스트를 위해, 에 의해 지배조종된다는 것입니다. <넌도미네이션으로써의 프리덤; 이소노미아>가 이 때문에 무효화되고, 왜곡되고, 변질됩니다. 이게 문제입니다.이러한 사회적인것들의 도미네이션(주도장악)을 <하우스 홀드의 국민국가화 또는 경제의 거대화>라고 잠정적으로 불러볼까 합니다. 다시말해서, 근대의 사회적인것들은 국민경제로의 거대팽창과 동시에 액트(비타 악티바)와 콘템플레이션(비타 콘템플라티바) 그리고 프리덤과 진정성의 위축과 무기력을 동반했다는 것입니다.이렇게 무기력해지고 위축된 비타 악티바(액트)를 되살리는 것, 이것이 한나 아렌트의 문제의식이 아닌가하고 나는 표상화합니다.