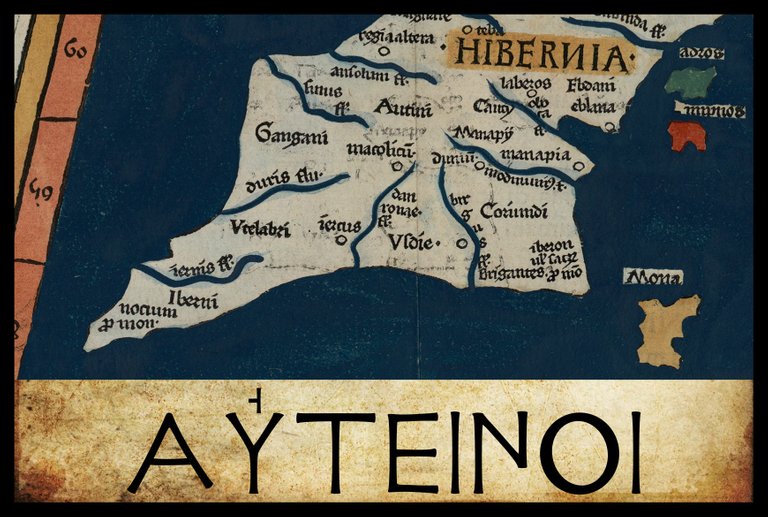

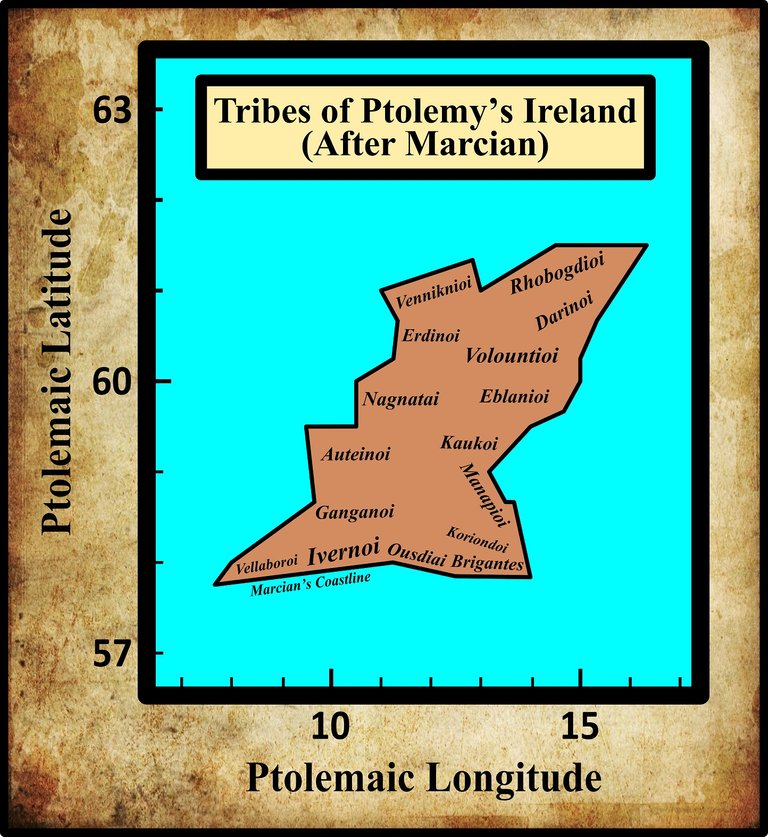

In his description of Ireland, Geography 2:2 §§ 1-10, Claudius Ptolemy records the disposition of sixteen Irish tribes. Resuming our voyage down the west coast of the island, the twelfth tribe we encounter are called the Auteinoi (Latin: Autini, Auteini). Ptolemy places these people immediately south of the Nagnatai.

In his 1883 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Karl Müller noted five variant readings of this ethnonym, but one of these differs from the critical form only in the application of the Greek accents. As the use of these accents was not regularized until the Byzantine era, they are generally considered to be “without authority” (O’Rahilly 1 fn 2, Gnanadesikan 220-221). Another of Müller’s variants seems to be a misreading on his part. This reduces the number of actual variants to three:

| Source | Greek | English |

|---|---|---|

| Most MSS | Αὐτεινοι | Auteinoi |

| M, X | Αὐτινοι | Autinoi |

| L2, α | Αὐτειροι | Auteiroi |

| Bertius | Αὐτεροι | Auteroi |

M is the Editio Argentinensis, which was based on Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation of Ptolemy (1406) and the work of Pico della Mirandola. Many other hands also worked on it—Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias Ringmann, Jacob Eszler and Georg Übel—before it was finally published by Johann Schott in Straßburg in 1513. Argentinensis refers to Straßburg’s ancient Celtic name of Argentorate.

X is Vaticanus Graecus 191, which dates from about 1296. It is believed that this manuscript preserves a very ancient tradition. Ptolemy’s description of Ireland is on folia 138v–139r.

α is identified by Müller as the Codex Ingolstadiensis. He refers to it as the Editio princeps, a term generally reserved for the first printed edition of a work. Today, the editio princeps is usually credited to Desiderius Erasmus, whose complete Greek edition—based on a manuscript provided by Theobald Fettich of Kaiserslautern—was published by Hieronymus Froben in Basel in 1533. Earlier in the same year, however, Peter Apian of Ingolstadt published an incomplete version of the Geography in Greek and Latin. I can only assume that Müller’s Cod α is a copy of this work.

L2 This is Burney MS 111 in the British Museum. The relevant data can be found on f.13v. According to Müller, this source gives the reading Αὐτενοι [Autenoi], but this is not the case. The reading is clearly Αὐτειροι [Auteiroi].

Bertius Petrus Bertius, a Flemish cartographer, whose printed edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, with Mercator’s and Ortelius’s maps, was first published in Amsterdam in 1618-19. Ireland is on Page 33. Note that Bertius includes the Latin variant Autini in the margin.

In his 1838 edition of Ptolemy’s Geography, Friedrich Wilberg also notes that the form Αὐτειροι [Auteiroi] appeared in the first three editions of Erasmus’s editio princeps, only to be replaced by the variant Αὐτεροι [Auteroi] for the fourth edition.

The substitution of the simple vowel ι [i] or ε [e] for the diphthong ει [ei] is easy to dismiss as a typographical error. However, the replacement of ν [n] with ρ [r] (or vice versa) is not so easily dismissed. In Byzantine minuscule, these two letters are not particularly similar and are unlikely to have been confused. In Ptolemaic script, however, the similarity is greater, so perhaps this variant is of long standing. The critical variant, Αὐτεινοι [Auteinoi], is justified on linguistic grounds, as we shall see.

Identity

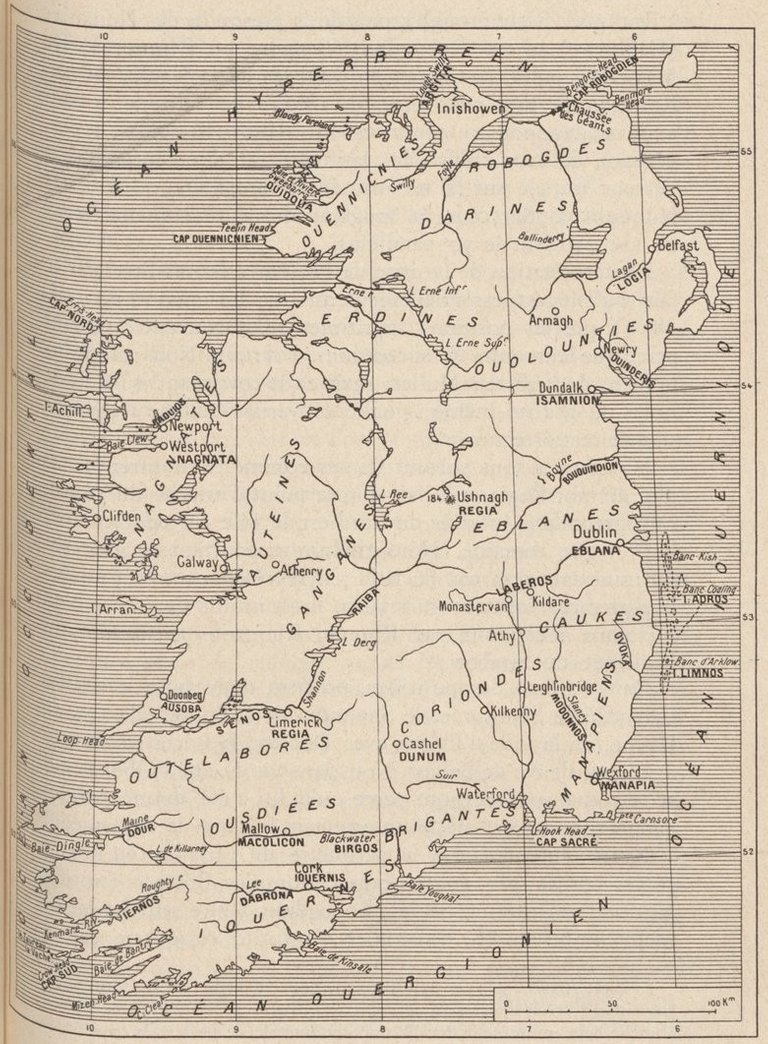

Over a century ago, the Irish historian Eoin MacNeill suggested that Ptolemy’s Auteinoi were the ancestors of the historical tribe known in our native records as the Uaithni. In early medieval times, the Uaithni dwelt on the left-bank of the River Shannon in Counties Limerick and Tipperary, but according to their own traditions they had once dwelt west of the Shannon, where Ptolemy places the Auteinoi:

Uaithnia, Druithnia, and Cainnia appear to be artificial eponyms of the Uaithni (hence the baronies of “Owney” in Tipperary and Limerick), Dál Druithne in Ui Maine (“west of the Shannon and north of Loch Derg”), and Caenrige (hence “Kenry” barony, co. Limerick). These Irish Ibdaig, like the Irish Picts, have Conall Cernach assigned to them as ancestor. Their traditional habitat (Kenry, Owney, Aidni, Ui Maine, Corcu Bascinn) seems to correspond with the position of the Auteni or Auteini (= Uaithni ?) in Ptolemy’s account. (MacNeill 102)

This hypothesis has found favour with later scholars, such as T F O’Rahilly:

Auteini. Mac Neill’s suggestion (Proc. R.I.A. xxix C, 102) that they may be identical with the Uaithni may be accepted without reserve. Uaithni would represent a Celt. *Autēniī or the like. Ptolemy places the Auteini approximately in Co. Galway. In historical times the Uaithni are located in the north-east of Co. Limerick and the adjoining part of Co. Tipperary, but tradition has it that at an earlier period they had dwelt west of the Shannon. The genealogists appear to have been very uncertain regarding the ethnic affiliations of the Uaithni. They agree in giving them as ancestor a mythical Fothad, [Footnote: Fothad is evidently a name for the ancestor deity ...] whom they split up into three brothers, but disagree notably as to their further origin ... Thus the only thing that is certain about the Uaithni is that they were of non-Goidelic origin. If we were at liberty to combine the contradictory accounts, we might suppose that they were of mixed Cruthnian, Ernean and Laginian descent. Their Laginian admixture, assuming it to be a fact, could have been acquired as a result of the Laginian (Dumnonian) conquest of Connacht, where the Uaithni originally dwelt. (O’Rahilly 10-11)

Cruthnian, Ernean and Laginian refer to the three principal Celtic peoples who colonized Ireland before the Goidels: the Priteni (c 750 BCE), the Belgae (c 500 BCE) and the Dumnonii (c 250 BCE).

While accepting MacNeill’s identification of Auteinoi and Uaithni, the contributors to the toponymic website Roman Era Names have added their own peculiar slant to the etymology of this ethnonym:

Αυτεινοι (Αυτινοι) (Auteinoi 2,2,5) lived in the west, modern county Galway, and were probably ancestors of the Uaithni. PIE *au- ‘off, away’ developed in many ways, including to OI úath ‘fear, terror’, from which a bad name translation as ‘the terrible ones’ has arisen. It is better to analyse this name as Au- ‘out’ plus -tenoi either as a banal adjectival ending ‘-tine’ often applied to peoples or, more likely, as like PIE *ten- ‘to stretch’ seen in early British names such as Τινα [Tina]. A name Autagis written on a Gaulish plate has been much discussed, notably by Delamarre (2003:62). Roman Era Names

The independent researcher Martin Counihan also accepts the Auteinoi-Uaithni identity, but adds some speculative flourishes of his own:

Ptolemy’s tribe of Auteini, in County Galway or thereabouts, developed into the group known in Old Irish as the Uaithni. It was eventually anglicised as Owney, whence the names of two baronies which lie to the east of Limerick city, Owneybeg (Little Owney) and Owney-and-Arra.

The Latin Auteini may well correspond to an Archaic Irish name with an approximate form aue-ítha-ini. The first element would be an early form of the Old Irish prefix úa, meaning a grandchild or descendant, which later (as óa, ui, ó, etc.) became extremely widespread in the formation of clan-names and territory-names and surnames. The middle element, ítha, is the genitive case of Íth, the name of a mythological ancestor of many of the Irish and particularly of the Érainn. The final element, ini, is a diminutive suffix. So, the Auteini or Uaithni were figuratively “the children of Íth”.

Íth was not a real individual, he was a deity, corresponding approximately to the Roman Saturn. Saturn was a god of agriculture and abundance, and it may be no coincidence that in Old Irish íth, as a common noun, meant “fat”. (Counihan 11)

More than a century ago, Rudolf Thurneysen had noted how an earlier Celtic or Indo-European au gave rise to the Old Irish úa, which came to be used as a prefix to proper names, with the meaning grandchild or descendant, the origin of the modern O’ in many Irish surnames:

60. ... Original au: úaithed úathad ‘singleness’, Gk. αὐτός [autos] ‘alone, self’, ON. auđr ‘desolate’; probably connected with the prep[osition] ó, úa ‘from, by’, Lat. au-ferre, O. Pruss. acc. sg. au-mūsnan ‘washing off’. (Thurneysen § 60 [§58 in the Handbuch])

Earlier Scholarship

The majority of the early scholars adopted the form Αὐτειροι [Auteiroi] or Αὐτεροι [Auteroi], which led them to formulate quite different etymologies for this ethnonym. William Camden set a trend when he linked the name of the Auteri to that of the town of Athenry in County Galway:

To the east [of the site of the Battle of Knockdoe], at no great distance from hence, stands Aterith (in which word the name of the Auteri is still preserv’d); it is commonly call’d Athenry, and is enclos’d with walls of great compass, but thinly inhabited. (Camden 1381)

The Irish antiquary James Ware also believed that the name of the tribe was connected with that of Athenry. Ware’s editor, Walter Harris, only noted that Athenry was antiently called Aterith (Ware & Harris 38). Athenry is actually quite a recent name, deriving from the Irish Áth na Riogh [Ford of the Kings] (Joyce 43).

William Beauford traced the name of the barony of Erris in County Mayo back to the Auteri, who he confidently asserted were evidently its ancient inhabitants (Beauford 60).

The Welsh scholar William Baxter glossed the name Auteiri as Aut Erion, which he translated into Latin as Ora Eriorum [Coast of the Irish].

Roderic O’Flaherty also opted for the form Auteri. He professed that he could make nothing of this name. He did subsequently note that it was supposed by some to be related to Athenry, but he is decidedly lukewarm when it comes to the etymological game:

We must indeed declare, that those tribes and septs which have been summed up by Ptolomy are as foreign to us in sound as the Savage nations of America; such as the Auteri ... The name of the Auteri is supposed to be derived from Athenry; that is Athnariogh, the ford of kings. What Irishman could refrain from laughter, hearing Regia or Rigia is wrested from Reglis, an ecclesiastical word of no great antiquity. (O’Flaherty 23-24)

In the early 19th century, Fr Charles O’Conor suggested that the Auteri were a branch of the Autrigones, a Cantabrian tribe of Northern Iberia mentioned by the 1st-century Roman geographer Pomponius Mela (Mela 216), and by Pliny the Elder (Pliny 172).

In the late 19th century, Karl Müller, who adopted the critical form Αυτεινοι [Auteinoi], noted a possible connection between Ptolemy’s Auteinoi and the name of an Irish island in the Ravenna Cosmography, an anonymous compilation of place-names from the early 8th century. Following a list of several islands, among which may be identified the Isle of Man, Anglesey and Rathlin Island, there is a list of twelve islands in another part of the ocean. Among these is Atina (Pinder & Parthey 441). Müller located this Atina in Galway Bay, though he gave no reason why:

Finally, Atina is one of the islands in Galway Bay, whose inmost recess is close to the city of Athenry and also the territory of the Autenoi, whom Ptolemy mentions. (Müller 76)

For the record, Athenry lies about 12 km inland of the easternmost recess of Galway Bay. The identity of Atina, like those of most of the islands in the list, is still a mystery. Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews hazards a guess at Muck in the Inner Hebrides—a long way from Galway Bay (Fitzpatrick-Matthews 82).

At the end of the 19th century, Goddard Orpen was still being seduced by the notion that the Auteinoi were somehow connected to Athenry, though it is Ptolemy’s “city” Ῥηγία [Rhēgia] that he identifies as Athenry:

The Αὐτεινοι (v. l. Αὐτενοι , Αὐτειροι) follow, with perhaps Ῥηγία [Rhēgia] as their chief seat. If this word be connected with the Irish rí, ríg, a king, we might guess it to be still represented by Athenry, Ath na Riogh, which is in about the right place. It must be observed, however, that it is not the Latin regia, but the Greek ῥηγία, that we have to deal with. (Orpen 119)

Conclusions

Despite some imaginative speculations on the part of recent scholars, there is a general consensus that Ptolemy’s Auteinoi represent the ancestors of the historical Uaithni, who are held by tradition to have once dwelt to the west of the river Shannon—precisely where Ptolemy places the Auteinoi. I concur.

References

- William Baxter, Glossarium Antiquitatum Britannicarum, sive Syllabus Etymologicus Antiquitatum Veteris Britanniae atque Iberniae temporibus Romanorum, Second Edition, London (1733)

- William Beauford, Letter from Mr. William Beauford, A.B. to the Rev. George Graydon, LL.B. Secretary to the Committee of Antiquities, Royal Irish Academy, The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 3, pp 51-73, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1789)

- André Berthelot, L’Irlande de Ptolémée, in Revue Celtique, Volume 50, pp 238-247, Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion, Paris (1933)

- Petrus Bertius, Gerardus Mercator, Abraham Ortelius, Theatri Geographiae Veteris Tomus Prior, in quo Cl. Ptol. Alexandrini Geographiae Libri VIII Graece et Latine, Jodocus Hondius, Amsterdam (1618)

- William Camden, Britannia: Or A Chorographical Description of Great Britain and Ireland, Together with the Adjacent Islands, Second Edition, Volume 2, Edmund Gibson, London (1722)

- Martin Counihan, Researchgate (2019)

- Patrick S Dinneen, Foclóir Gaedhilge agus Béarla: An Irish-English Dictionary, Irish Texts Society, M H Gill & Son, Ltd, Dublin (1904)

- Keith J Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Britannia in the Ravenna Cosmography: A Reassessment, Academia (2013)

- Amalia E Gnanadesikan, The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester (2009)

- Patrick Weston Joyce, The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places, Volume 1, Longmans, Green, & Co, London (1910)

- Eoin MacNeill, Early Irish Population-Groups: Their Nomenclature, Classification, and Chronology, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Volume 29 (1911/12), pp 59-114, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin (1912)

- Pomponius Mela, Karl Heinrich Taschucke (editor), De Situ Orbis Libri Tres, Friedrich Christian Wilhelm Vogel, Leipzig (1816)

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller (editor & translator), Klaudiou Ptolemaiou Geographike Hyphegesis (Claudii Ptolemæi Geographia), Volume 1, Alfredo Firmin Didot, Paris (1883)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 1, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Karl Friedrich August Nobbe, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia, Volume 2, Karl Tauchnitz, Leipzig (1845)

- Charles O’Conor, Rerum Hibernicarum Scriptores Veteres, Volume 1, Prolegomena, Pars I, John Seeley, Buckingham (1814)

- Roderic O’Flaherty, James Hely (translator), Ogygia, Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, Volume 1, W McKenzie, Dublin (1793)

- Thomas F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1984)

- Goddard H Orpen, Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland, The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Volume 4 (Fifth Series), Volume 24 (Consecutive Series), pp 115-128, Dublin (1894)

- Moritz Pinder, Gustav Parthey (editors), Ravennatis Anonymi Cosmographia et Gvidonis Geographica [The Cosmography of the Anonymous of Ravenna and the Geography of Guido of Pisa], Friedrich Nicolai, Berlin (1860)

- Pliny the Elder, John Bostock, Henry Thomas Riley, The Natural History of Pliny, Volume 1, Henry G Bohn, London (1855)

- Claudius Ptolemaeus, Geography, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat Gr 191, fol 127-172 (Ireland: 138v–139r)

- Rudolf Thurneysen, Osborn Bergin (translator), D A Binchy (translator), A Grammar of Old Irish, Translated from Handbuch des Altirischen (1909), Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin (1946, 1998)

- James Ware, Walter Harris (editor), The Whole Works of Sir James Ware, Volume 2, Walter Harris, Dublin (1745)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Wilberg, Claudii Ptolemaei Geographiae, Libri Octo: Graece et Latine ad Codicum Manu Scriptorum Fidem Edidit Frid. Guil. Wilberg, Essendiae Sumptibus et Typis G.D. Baedeker, Essen (1838)

Image Credits

- Ptolemy’s Map of Ireland: Wikimedia Commons, Nicholaus Germanus (cartographer), Public Domain

- Greek Letters: Wikimedia Commons, Future Perfect at Sunrise (artist), Public Domain

- T F O’Rahilly: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

- André Berthelot’s Map of Ptolemy’s Ireland: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public Domain

- The Fields of Athenry, with Galway Bay in the Background: © 2019 The Irish Times, Fair Use

Congratulations @harlotscurse!

Your post was mentioned in the Steem Hit Parade in the following category:

Hi harlotscurse,

Visit curiesteem.com or join the Curie Discord community to learn more.