— Claimed to be

said by Epicurus

Philosophy is a strange subject to cover, as one of the pinnacle philosophical questions is the very subject itself — "What is philosophy?". There are presumably as many conceptions of philosophy as there are philosophers. And even amongst philosophers themselves, there are inconsistencies in what exactly the practice of philosophy entails.

Modern conceptions of philosophy are all but locked up in academia. Rarely does one find any attempt to bring philosophy out of this stronghold. Even though there are some pop-phil or popular philosophy books on the market, these rarely hit the mark.

Take, for example, the modern revival of Stoic philosophy, spearheaded by the likes of Massimo Pigliucci, or the many philosophy books of the School of Life spearheaded by Alain de Botton. While these attempts at returning philosophy to the agora (marketplace) or public discourse might be commendable, they fall short in many respects (which the general public who read these books do not know about).

The most notorious of these claims is that these popular philosophy writers, amongst other things, grossly oversimplified philosophical arguments which lead to misunderstandings and confusion, but also that they cherry-pick what works for them and conveniently leave out what does not work in their framework. The metaphysical assumptions of, for example, ancient Stoic philosophy are conveniently overlooked as it does not hold any longer in modern scientific communities. Other gross misunderstandings of, for example, Descartes' mind-body dualism and Nietzsche's nihilism pervade modern public discourse — doing a disservice to the sometimes incredibly complex and nuanced arguments of these philosophers.

This post, or book review, however, is not on the problems of popular philosophy. Instead, I want to review Philosophy as a Way of Life, a book written by the philosopher and historian Pierre Hadot. Contrasted against the above notion of popular philosophy and the authors who sometimes oversimplify and misunderstand complex arguments, the work of Hadot is a breath of fresh air amongst the clouded judgements of popular philosophy and also the dusty jackets of verbose and dry academic philosophy.

Philosophy as a Way of Life finds a strange middle way or in-between space between academic philosophy and what we have called so far pop-philosophy.

The main premise of the book by Hadot, and all of his other works, is very simple: We should make a distinction between what he calls philosophy and philosophical discourse. Philosophy, according to Hadot, is lived, practised, and exercised on a constant and daily basis. Philosophical discourse, on the other hand, is a set of texts, or theories, which might underlie philosophy (as a way of life) but which was never intended to inform one's daily life. This amounts to modern-day philosophical treatises, which most people find really dry. Hadot is critical of the latter, especially if it is not accompanied by some form of philosophy. He writes, for example, that

“[a]ncient philosophy proposed to mankind an art of living. By contrast, modern philosophy appears above all as the construction of a technical jargon reserved for specialists.” (Hadot, 1995:272)

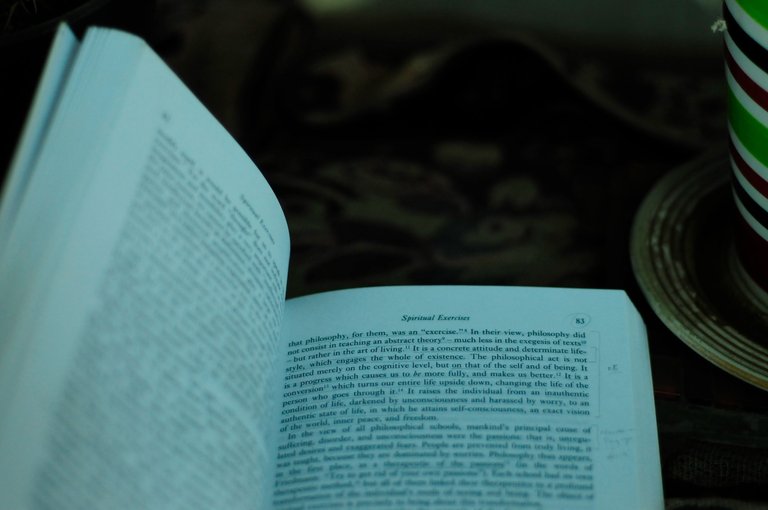

This is the crux of the essay title the same as the book. In this short essay, which one might basically see as a summary of the whole book, Hadot explains how the ancient Greek philosophers did not see philosophy as an academic subject devoid and detached from everyday living. In fact, the rather rigid claim by Hadot is that philosophy was not at all like what we have today: philosophy was lived, practised, exercised, articulated, verbalised, and again, practised.

The quote of Epicurus which I highlighted at the start of this post or book review speaks to this; "vain is the word of the philosopher that does not heal..." What this meant, especially when we follow Hadot, is simply that the words of a philosopher that cannot be put to practice, which does not affect how one might live, are not worthy. In ancient Greece, if one could not practice one's philosophy, it was not a good philosophy. This is one of the reasons, according to Hadot, why we find various accounts of these philosophers which might not be factually true. Think of the Skeptics who apparently walked from cliffs because they did not believe the drop was there. The reason for these accounts was to show the commitment of individual philosophers to their philosophical thoughts/schools. But it was also linked to the fact that philosophy was seen as a cure to everyday ailments, like anxiety about death, one's future, and so on. In a memorable line, Hadot notes that the stress we feel today is of a similar kind to what the ancients dealt with.

Along with this idea of philosophy was the notion now popularised (in the field of practical philosophy) of spiritual exercises. Various schools of thought, such as the Stoics, Epicureans, and even the Skeptics, continually practised their philosophies through various regiments. From dietary changes, to daily reminders that death is nothing, to daily meditations in the form of writing, the participants of these schools trained their whole being in line with the school of their choice.

One of the most known spiritual exercises, popularised by Plato, but even maintained throughout European history, was the notion of philosophy being training for one's death. Another spiritual exercise, used by amongst others, Marcus Aurelius and taken up by modern philosophers like Descartes, was meditations — the practice of, for example, writing down how insignificant one's own life was, how death could not touch one, how the body is nothing but a composite of strange material, and so on.

Philosophy therefore could not be seen as a mere academic practice that one takes on as a job (think of the philosophy professor today in academia). Instead, philosophy demanded one's whole being in the world, and thus the notion of a radical conversion. Philosophy, as Hadot tells us countless times, demanded a radical conversion of anyone who dared adopt it as a way of life. This brought about, what one might call, a rupturing of daily life, and caused the philosopher to become a strange creature...

By adopting philosophy as a way of life, one does not just rupture everyday life — the radical conversion demanded a total reformation of how own lived —, but one becomes strange, or the Greek term atopos, unclassifiable. The state of being a philosopher is thus inherently strange and unclassifiable exactly because the philosopher is said to be in love with wisdom — a state of being not necessarily accessible to humans but one to which we strive, move, journey, adventure, progress (it becomes a whole life pre-occupation, one that is never-ending and always developing). That is, the ancient Greek philosophers did not think that one could become a sage, one who has complete wisdom. That is why one is a philosopher, a lover of wisdom; philo-sophia becomes a journey, something we partake in without every finding the destination. I want to end this book review with another Epicurus quote:

This echoes Aristotle who held the same idea; we philosophise for the sake of philosophising, and not to get something from it. Hadot, through this book, aims toward the same thing: we philosophise to become better humans, to strive toward wisdom but with the knowledge that we will never arrive. After all, we are reminded by the likes of Plato, Michel de Montaigne, and Hadot himself, that philosophy is after all just a training for death.

This book is by no means an easy read. And it is by no means in the genre of popular philosophy. In fact, I do not think that the general public might gain much from the book as it is, unless one has a keen sense of interest in ancient Greek philosophy. But the wisdom — or rather aim towards wisdom — is of immense worth. Hadot was not just a philosopher but a historian, and this might add to the difficulty of the book and the overall oeuvre of Hadot. Some of the arguments are very technical, and some of the essays are extremely dense. But the timely wisdom hidden in these passages, I would argue, can help the general public in more ways than one.

Recently, I published an article in an academic journal on philosophy as a way of life, and I will continue to write about it as I perceive it to be a tremendously important yet underexplored facet of philosophy. In fact, I want to write a book about this very topic. Maybe in the future, I will get the time to explore this more.

I hope that you enjoyed this book review interspersed with my own reflections. I could have written much more about it, but it is already very dense. Throughout my writings, I have tried to practice philosophy as a way of life, so there might be breadcrumbs all over my writing. But I hope that I have kind of summarised the argument above.

For now, happy reading, and keep well.

All of the musings, reflections, and writings are my own, albeit inspired by so many philosophers who lived their philosophies, or unless I hyperlinked something. Some of the above are direct quotes as indicated. The photographs are also my own, taken with my Nikon D300.

The Fermented Philosopher's Library

| 🕮 The Book of Malachi | 🕮 The Outsider | 🕮 A Clockwork Orange | 🕮 Perfume |

|---|---|---|---|

| by T.C. Farren | by Stephen King | by Anthony Burgess | by Patrick Suskind |

| 🕮 The Uninvited | 🕮 Life Is Elsewhere |

|---|---|

| by Geling Yan | by Milan Kundera |

Congratulations @fermentedphil! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 7500 replies.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts: