Nobody will be interested in cinema

The story of Frenchman Georges Méliès, full of glamorous successes and resounding failures, represents an essential chapter in understanding the development of cinema as we know it today. Georges Méliès was a magician. Literally: a magician with a long professional career when he was struck by Louis Lumière's invention. On December 28, 1895, he was among the amazed spectators at that first public showing of the Lumiére cinematograph. He immediately wanted to buy the invention, but Lumière did not accept. It is said, but it is possible that the anecdote is not true, that the father of the inventors refused to sell it to him, considering that he was doing him a favor: “This is only of scientific interest. In a year's time, no one will be interested in it”, he told him, very sure of his statement. And, truth be told, the prediction almost came true, as we will see below.

One day, while filming in the streets of Paris, the camera stopped, but George didn't notice; soon after, it started working again. When he developed the film, he had before his eyes an extraordinary event, a passenger vehicle suddenly transformed into a hearse. Amazing! What had happened was obvious; the tape had stopped for a moment, but the traffic had continued to pass.

George Méliès had just discovered the first cinematographic trick: the substitution of one object for another. The director's magician's mind soon came up with another trick: the disappearance of people, objects and animals, and then overprints, the registration on a previously filmed tape. We are already installed in what we now know as special effects. It is possible that some other forgotten director may have discovered these tricks before Méliès, but he was the first to investigate and experiment systematically with them in his films, which is a major merit and reason enough for his name to be revered by later filmmakers.

Fantasy on the screen

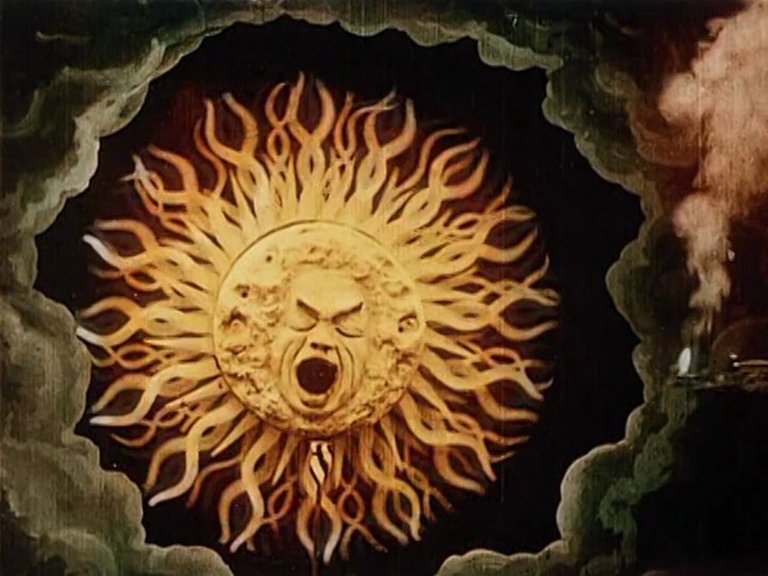

Source: Still from Journey to the Moon

With these technical resources and his theatrical repertoire, Méliès embarked on a new stage. The era of cinematographic magic acts began. In a typical film of that era, Méliès would appear on the screen full-length, greet the audience and perform various acts of apparitions and disappearances of objects and people. But he realized that this did not have much of a future either, and he introduced more and more narrative elements to his magic acts. In other words, he began to construct stories, short at first, and then longer and longer.

Méliès is a great success. He founds a production company, Star Films, and builds a studio in an estate he owns on the outskirts of Paris.

Between 1896 and 1912, he made more than 500 films that were distributed throughout Europe and the United States. Some of these films have become true icons of silent cinema, such as 1902's Journey to the Moon, loosely inspired by Jules Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon. This was followed by 1903's The Fairy Kingdom and 1904's Journey Through the Impossible.

These films were large productions for the time, with real boasts of production, scenery and a large number of actors and actresses on stage, in addition to putting into images all the special effects that Méliès knew and others that he was inventing. As if this were not enough, it can be said that with these films, and others that followed, the French director inaugurated the science fiction and fantasy genres, which have had such a long life on the screens.

Although, as we said before, Méliès made more than 500 films in different genres, including documentaries and reconstructions of historical events, his main contribution is in fantastic and science fiction cinema with a major emphasis on adventures. His cinema is not one of reflection or denunciation, but of action and magic.

The end of the illusion

By 1910, Méliès' style had begun to become old-fashioned. Charming though they were, his films had not changed with the development of cinematic language, which had evolved rapidly.

Let's look at this in more detail. The reference point of Georges Méliès's cinematographic activity was always the theater. Or rather, the perspective of a theatrical spectator. His vision is frontal and full-body. The acting is of exaggerated and extravagant gestures, the camera does not move. His set designs are striking and beautiful, but clearly theatrical.

As the film historian Román Gubern says:

Méliès' creations are the fruit of the meeting of two distinct techniques: that of the photographer and that of the man of theater and illusionist. His films are often divided into “frames” or “scenes” which, conceived according to the canons of theatrical art, advance the narrative. In this way, the camera is limited to being an immobile apparatus that photographically reproduces what is happening on stage.

The rising cost of his films and the piracy of the time led to the ruin of Georges Méliès, who had to sell his company and studio to one of his rivals to pay off his debts. He died in 1938 in an asylum for old filmmakers. In 1931 he received the Legion of Honor and the admiration, somewhat nostalgic, of many artists and creators who saw in him a manifestation of the grace of childhood.

However, the harsh reality is that since the early years of the twentieth century, filmmakers were exploring other directions than those of Méliès, with stories closer to the viewers. Realism began to make its way into cinema as the camera learned to move and the image became more dynamic, moving closer to or further away from the viewer as the narrative required.

In short, it was with Georges Méliès that cinema took the definitive leap towards fiction and became a great mass spectacle and a flourishing industry of increasingly international scope. In its first decade and a half, cinema lacked a language of its own; its narrative and staging resources responded to theatrical conventions, but it soon defined its means with the development of shots and camera movements, as well as with the exploration of the possibilities of montage.

Georges Méliès was born in 1861 in Paris, and died in 1938 in poverty, in the same city where he was born, in an asylum for old filmmakers.

Congratulations @rjguerra! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 30000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts: