Location and Dates

The Volyn Massacre occurred in the region of Volhynia (Volyn) during World War II, primarily from March 1943 to the end of 1944. Located in what was then eastern Poland and now part of western Ukraine, the violence was part of a broader ethnic conflict between Poles and Ukrainians. The massacre was driven by Ukrainian nationalist groups, particularly the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), seeking to create a Ukrainian state free of Polish influence. The peak of the violence occurred during the summer of 1943, with July 11, known as the "Bloody Sunday", standing out as one of the deadliest days, with coordinated attacks on 100 Polish villages.

Galicia

Galicia is a historical region in Eastern Europe, which is currently divided between western Ukraine and southeastern Poland. The region's borders have shifted over time, but it is generally centered around the cities of Lviv (in Ukraine) and Kraków (in Poland), with the Carpathian Mountains to the south.

Historically, Galicia was part of several empires and states, including the medieval Kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and later interwar Poland before being annexed by the Soviet Union during and after World War II.

Galicia is known for its ethnically diverse population, historically including Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, Armenians, and Germans, which contributed to both its rich cultural history and ethnic tensions. After World War II, most of Galicia's Polish population was relocated, and the region was incorporated into Soviet Ukraine, leading to the demographic predominance of Ukrainians today.

Throughout its history, Galicia has been a focal point of both nationalist movements and ethnic strife, especially between Poles and Ukrainians, culminating in events such as the Volyn Massacre. Today, it remains an important cultural and historical region for both Poland and Ukraine.

Number of Deaths

The massacre resulted in the deaths of between 50,000 and 100,000 ethnic Poles, many of whom were civilians. The killings were marked by their brutality, often involving mass executions, mutilations, and destruction of entire villages. While the majority of the victims were Polish, there were also thousands of Ukrainians killed in retaliatory actions by Polish resistance forces. The killings occurred against the backdrop of broader ethnic cleansing efforts during the war and involved systematic efforts by Ukrainian nationalists to remove the Polish presence from Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.

Historical Issues of the Area

Volhynia has long been a region of contested control between Poles and Ukrainians, with ethnic tensions exacerbated by the shifting political boundaries of the 20th century. In the interwar period, Volhynia was part of Poland, but it was home to a significant Ukrainian population that felt politically and culturally oppressed under Polish rule. The UPA, under the leadership of Stepan Bandera, sought to use the chaos of World War II to establish an independent Ukrainian state, targeting Poles in an effort to ethnically cleanse the region. The violence was fueled by nationalist ideologies and a desire to reshape the ethnic map of the area.

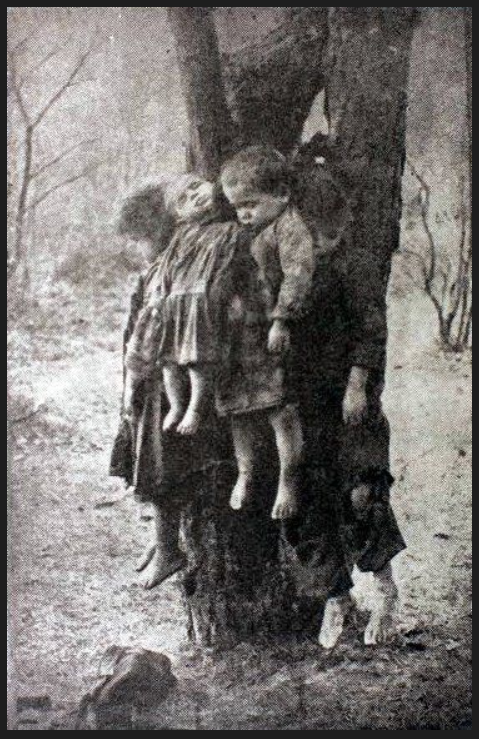

Monument with the Child Skewered on a Trident

One of the most harrowing symbols of the Volyn Massacre is the image of a Polish child skewered on a trident, a symbol of the Ukrainian coat of arms. This grotesque imagery represents the extreme violence perpetrated against civilians, including women and children. The monument depicting this act serves as a reminder of the brutality of the massacre and has become a focal point for Polish memory of the event. The monument has been controversial, particularly in Ukraine, where it is seen as a stark and accusatory representation of Ukrainian nationalism. For many in Poland, it stands as a symbol of the innocence of the victims and the unprovoked nature of the massacre, but in Ukraine, it complicates national narratives about resistance and independence.

Stepan Bandera and the Extreme Ukrainian Cultural Perspective

Stepan Bandera, a prominent figure in Ukrainian nationalism, remains a deeply divisive figure, both in Ukraine and abroad. Bandera was the leader of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B), which sought to achieve Ukrainian independence through violent means, including collaboration with Nazi Germany and ethnic cleansing of Poles and Jews. While Bandera's role in the Volyn Massacre itself was indirect (he was imprisoned by the Nazis at the time), the ideology he promoted inspired many of the UPA fighters responsible for the killings.

In post-Soviet Ukraine, Bandera has been lionized by segments of the population, particularly in western Ukraine, as a hero of the struggle for Ukrainian independence. Streets, monuments, and even state honors have been named after him, reflecting a nationalist perspective that sees him as a symbol of resistance against both Soviet and Polish domination. However, for Poland and many in the international community, Bandera's legacy is tainted by his involvement in war crimes, including the Volyn Massacre, and collaboration with the Nazis.

Bandera's image has complicated Ukraine's efforts to reconcile with Poland over the Volyn Massacre. While some Ukrainians view Bandera as a freedom fighter, others, particularly in the more Russian-speaking east, see him as a symbol of extremism. The Polish government has consistently pushed for Ukraine to acknowledge the crimes committed by Bandera's followers, leading to diplomatic tensions. In Ukraine, particularly amid the war with Russia, Bandera has been re-embraced by some as a nationalist symbol of Ukrainian identity and resistance.

HIstorical wars

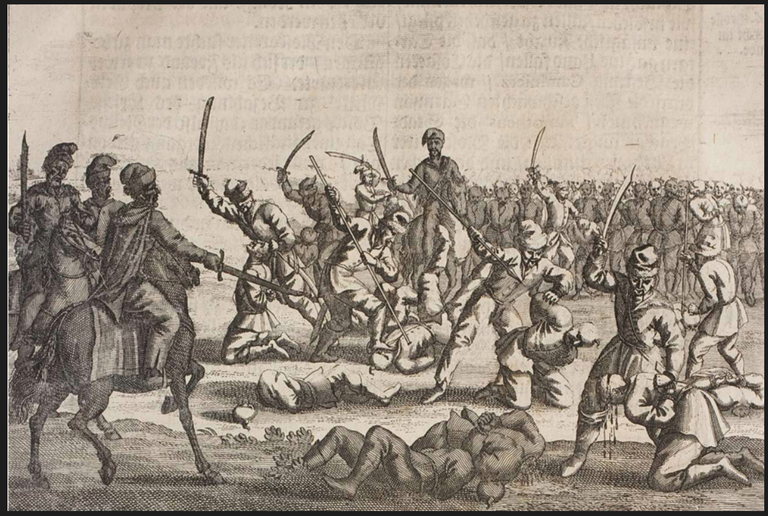

Ukrainian nationalism is the ideology promoting the unity of Ukrainians into their own nation state, Ukraine. Although the current Ukrainian state emerged fairly recently, some historians, such as Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Orest Subtelny, and Paul Robert Magocsi, cited the medieval state of Kyivan Rus as an early precedent of specifically Ukrainian statehood. The origins of modern Ukrainian nationalism are also traced to the 17th-century Cossack uprising against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth led by the Ukrainian Cossack Hetman Zynoviy Bohdan Khmelnytsky (1595 – 1657). Khmelnytsky led an uprising against the Commonwealth and its magnates (1648–1654) that resulted in the creation of a state led by the Cossacks. This Cossack-Polish War, the Chmielnicki Uprising, the Khmelnytsky massacre or the Khmelnytsky insurrection, was an Ukrainian Cossack rebellion that took place between 1648 and 1657 in the eastern territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which led to the creation of a Cossack Hetmanate in Ukraine.

Current Issues Between Poland and Ukraine

The memory of the Volyn Massacre continues to strain relations between Poland and Ukraine. Poland officially recognizes the massacre as genocide, a term rejected by most Ukrainian leaders. In 2016, the Polish parliament passed a resolution commemorating the victims of the massacre and declaring it an act of genocide, further complicating diplomatic efforts between the two countries. In contrast, Ukrainian leaders, including President Volodymyr Zelensky, have taken steps to acknowledge the massacre but have refrained from using the term genocide, citing the broader context of mutual violence during the war.

Poland has consistently called for Ukraine to formally apologize for the killings and recognize the UPA's role in the atrocities. Ukraine, meanwhile, has focused on the broader narrative of wartime suffering, highlighting Ukrainian civilian casualties at the hands of both Polish forces and Soviet troops. This difference in historical interpretation remains a sticking point in bilateral relations, particularly as both countries attempt to navigate their shared history amid broader European security concerns.

The current Russia-Ukraine war has somewhat softened these tensions, as Poland has been a staunch supporter of Ukraine against Russian aggression. This has led to greater cooperation, but the unresolved legacy of the Volyn Massacre continues to pose challenges for long-term reconciliation.

Conclusion

The Volyn Massacre remains one of the darkest chapters in Polish-Ukrainian history, marked by extreme violence, ethnic cleansing, and deep-rooted historical grievances. The massacre is a flashpoint for contemporary political relations between Poland and Ukraine, both of which seek to assert their own historical narratives. The monument depicting the skewered child is a stark reminder of the brutality of the massacre, while figures like Stepan Bandera continue to polarize views within Ukraine and complicate efforts at reconciliation with Poland. As both nations look to the future, efforts to confront this painful past remain essential for any lasting resolution.

While progress has been made through diplomatic gestures and shared commemorations, the full political resolution of the Volyn Massacre is still an ongoing process. Reconciliation efforts will require continued dialogue and a willingness on both sides to grapple with the complex and often painful legacy of this dark period in history.

Further Reading

https://volhyniamassacre.eu/zw2/history/173,What-were-the-Volhynian-Massacres.html

As with all wars, it's the innocents who pay the highest price. It often amazes me just how easily people can turn to a belief that an entire culture deserves to be eradicated down to the children, because they will grow up to become the same perceived evil as the adults.

Sadly these kinds of massacres are all too common throughout history and throughout the world. It seems we'll always have a never ending cycle of struggling to forgive each other for the past atrocities of our ancestors.

yes, there are always a distinct patterns that occurs that culminates into such violence.

I'll have to find the passage in the book, (I think) Barbarossa, but there was a stage of the battle between the Russians & Germans, fighting in Poland, where both armies were having a soft truce, each washing their clothes on either side of a River in Poland.

Whereas, 2 different Polish "resistances" were killing each other, and the big boys left them to fight it out while they did their laundry.

Once the ball of violence gets rolling it gets out of hand pretty quickly.