Introduction

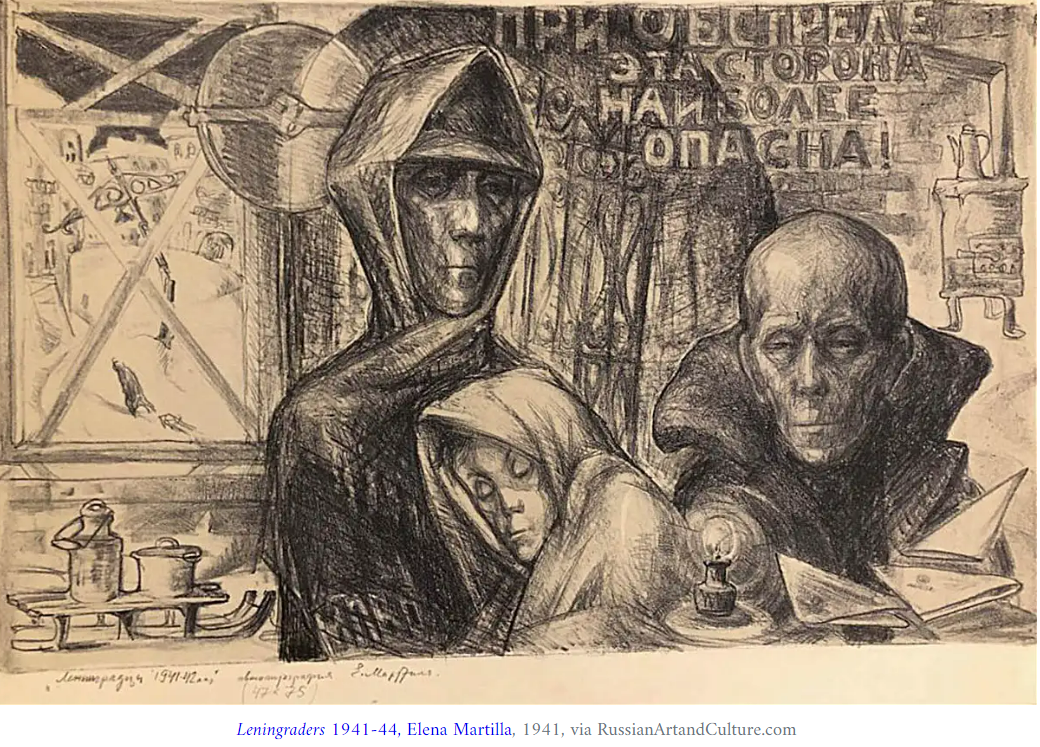

Eighty years ago on 27 January 1944 the Red Army finally ended Nazi Germany’s siege of the city of Leningrad which killed over a million of its citizens. Hitler, unable to conquer the city off the march and desperate to take Moscow before the end of 1941, instructed the German Eighteenth Army to lay siege to the 2.5 million inhabitants of Leningrad. He was confident it would be quick and easy. However the siege, which began on 8 September 1941, lasted for a total of 872 days (although often referred to as the 900 Day Siege).

German Invasion of the Soviet Union

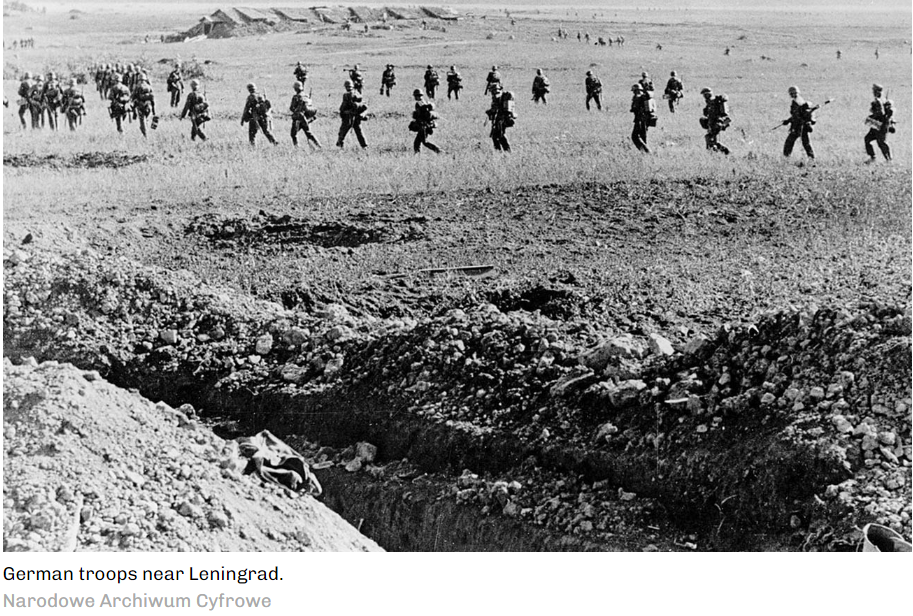

On 22 June 1941 Nazi Germany launched its invasion of the Soviet Union. The Wehrmacht made rapid progress on every front as it confronted a Red Army whose leadership had been greatly weakened by Stalin during the murderous purges of the late 1930s.

As the Panzer units of Army Group North sped northward, towards their prize of capturing Leningrad, the commander of Fourth Panzer Group Colonel-General Hoepner issued an operational order on how the troops were to conduct themselves in this ‘war of annihilation’:

This war must have as its goal the destruction of today’s Russia – and for this reason it must be conducted with unheard of harshness. Every clash, from its inception to its execution, must be guided by an iron determination to annihilate the enemy completely and utterly. There is to be no mercy for the carriers of the current Russian-Bolshevik system.

By 8 July Panzers had crossed the Latvian-Russia border and breached the Stalin defensive line. Field Marshall Leeb, commander of Army Group North, sent a triumphant message to his troops, “The enemy’s attempts to construct a defensive front on the old Russian border have failed. We have broken through. Army Group North now attacks in the direction of Leningrad!”

On hearing this news Goebbels, who was with Hitler in his Wolf’s Lair headquarters, wrote in his diary about the genocidal intentions of the Nazi regime towards the inhabitants of Leningrad:

No one now doubts that we shall be victorious in Russia. Of Bolshevism, nothing will be allowed to remain. The Fuhrer intends to have cities like Petersburg rubbed out.

On 12 July Hitler released the XXXIX Motorised Crops to reinforce the drive towards Leningrad.

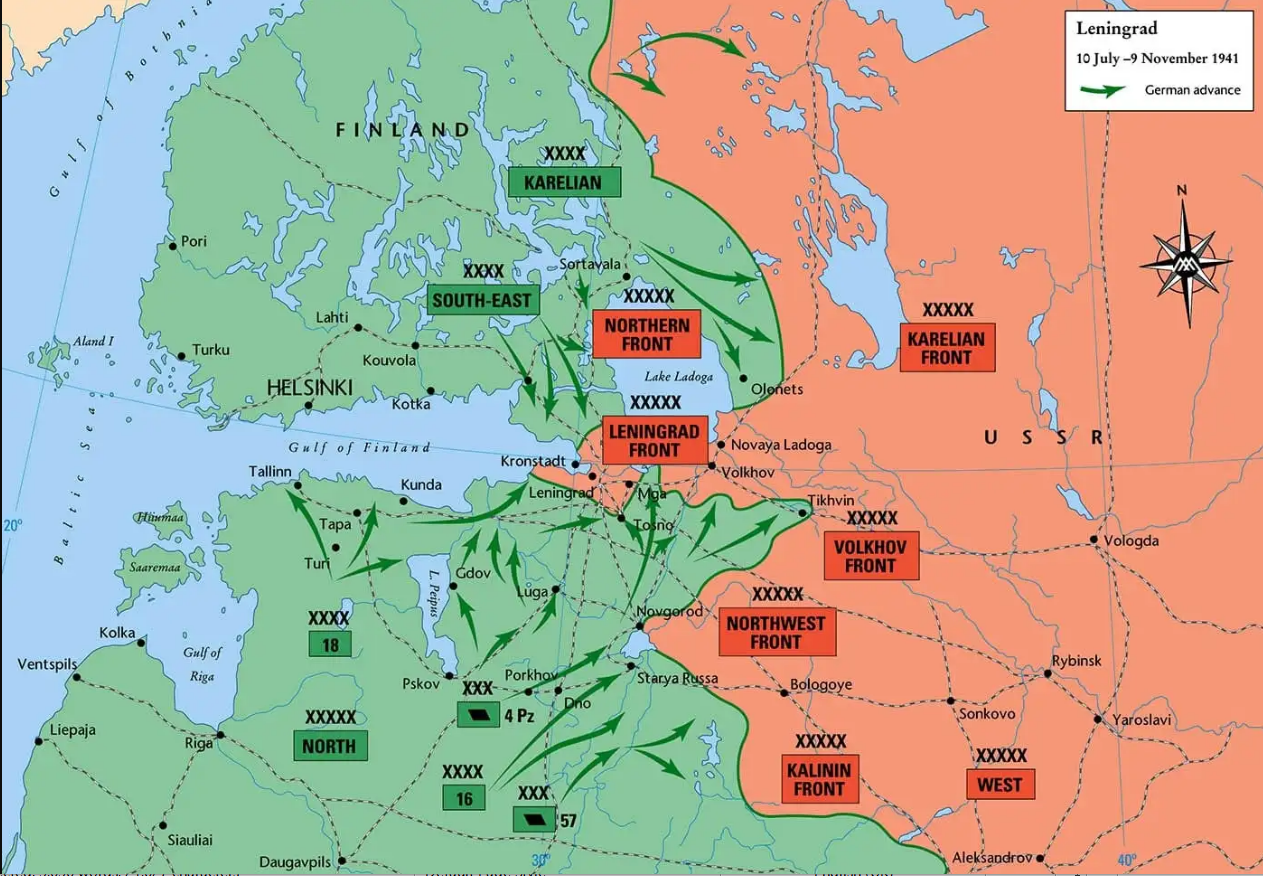

As Soviet forces retreated through the Stalin Line huge gaps appeared in the front. General Zhukov ordered the Luga Operational Group to defend the approaches to Leningrad and Tallinn along the so-called Luga Line. Work on the defences of this line of fortifications had only begun on 29 June. This new defensive line extended 187 miles from the Gulf of Narva to Lake II’men.

The Luga line, whose defences were incomplete and fragile, was to be partly manned by newly formed people’s militia divisions (DNO). The hopelessly incompetent Marshal Voroshilov, an old friend of Stalin’s from the 1918-1920 civil war, was given command of the Northern and Northwestern Fronts. On 14 July he issued Order No.3 which demanded Red Army units hold Leningrad “at all costs.”

Army Group North resumed its advance on 10 July and the new Soviet defensive line soon began to crumble. Despite fanatical resistance, which in one notable instance on the Luga River, held up the 1st and 6th Panzer Divisions for six days, the Wehrmacht made rapid progress on all axis towards Leningrad. The most notable being the 8th Panzer Division which on 13 July advanced 25 miles and reached the town of Sol’tsy.

David Glantz in his book, The Siege of Leningrad 900 Days Of Terror, observes that:

Red Army attempts to halt the Germans were heroic but disastrous, as Soviet units were continually outflanked and surrounded by a more organized and mobile enemy.

He further notes how Soviet units suffered from poor command, control and coordination in battle further reducing their combat effectiveness.

The Finnish advance in Karelia forced Voroshilov to send precious reserve units from the defunct Luga Line to stem the tide further north. By late July Voroshilov finally recognised that the Luga Line was not going to stop the German advance and ordered the construction of the Krasnogvardeisk Fortified Region to defend the approaches to Leningrad.

Unhappy with the performance of his friend Stalin summoned Voroshilov to Moscow on 30 July where the hapless Marshall was savaged by his boss for a “lack of toughness’’ in conducting military operations to halt the German advance.

In response to the unfolding crisis Stalin ordered the defences south of Leningrad to be strengthened and the Thirty Fourth Army and newly formed Forty Eighth Army were dispatched to the Northwestern Front.

Meanwhile, Hitler and his senior generals formulated their final plans for the advance on Leningrad. On 19 July Fuhrer Directive No 33 ordered Wehrmacht forces to “prevent the escape of large enemy forces into the depths of Russia and to annihilate them.’’ A subsequent directive ordered the capture of Leningrad before the taking of Moscow and assigned the Third Panzer Group to Army Group North to enable it capture the birthplace of the Soviet state.

Optimistic as ever at this early stage of the war Hitler further reinforced Army Group North with V111 Air Corps and ordered Marshall Leeb, commander of Army Group North, to “initiate the offensive on Leningrad, encircle the city, and link up with the Finnish Army.”

Leeb divided Army Group North into three offensive fists with the bulk of his forces focused on the advance on Leningrad. He also planned major operations on his flanks with the intention being to clear Red Army units from the Estonian coastline and Tallinn while further south, in the Lake II’men area, his men were to defeat the Soviet Eleventh, Thirty-Fourth, Twenty-Seventh and Twenty-Second Armies and cut the vital Moscow-Leningrad railroad. This audacious offensive had a mere three security divisions in reserve.

The German offensives made rapid progress but did face a minor setback when a Soviet counter-attack, launched on 12 August, forced the German High Command (OKH) to divert forces away from the vital Leningrad axis to eliminate the threat to the southern flank around Lake II’men. By 31 August four German motorised corps along with the 19th Panzer Division had captured Demiansk. Another triumph came on the same day when the 20th Panzer Division and 11 Army Corps inflicted a major defeat on Soviet forces at Molvotitsy and closed the gap between Army Groups North and Centre.

All of this activity came at a great cost to Army Group North for, as Glantz has pointed out, it “seriously weakened and delayed the advance on Leningrad and the fighting itself took a toll on German strength; for by this time, army Group North’s losses stood at a massive 80,000 men.’’

Yet the toll on Soviet forces was much greater.

By late August the newly created Forty-Eighth Army had been decimated and reduced to a mere 6235 men, 5043 rifles and 31 artillery guns with which to defend the southeastern approaches to Leningrad. By this point Stalin’s patience with the hopelessly incompetent Voroshilov was coming to an end as German units were only 25 miles south-west of Leningrad and had also reached Chudovo which was only 62.5 miles south-east of the city. Even worse for Stalin was the fear that Wehrmacht forces advancing east of Leningrad would link up with the Finnish army and encircle the city.

By early September the forces of the Leningrad Front ‘were a shambles’ as German units had torn a huge gap in the Soviet defensive line south-east of the city. On 29 August the 20th German Motorised Division had captured Tosno and reached the Neva River and was on the verge of severing the last Leningrad railroad line to the east.

The Start of the Siege

On 7 September, after several days of intense fighting, the defences of the Forty-Eighth Army south of Lake Ladoga cracked and the 12th Panzer Division, together with the 20th Motorised Division, captured Siniavino and then occupied Shlissel’burg the next day. This disaster signalled the beginning of the German blockade of Leningrad. The OKH triumphantly announced in a communique to all troops that “the iron ring around Leningrad has been closed.”

Glantz has described the momentous significance of the capture of Shlissel’burg by German forces:

The capture of Shlissel’burg on 9 September gave the Germans total control over all of Leningrad’s ground communications with the remainder of the country. Henceforth, re-supply of the city was only possible via Lake Ladoga or by air.

Hitler and his generals now felt that Leningrad was theirs for the taking. In September General Halder, the OKH Chief of Staff, wrote in his diary that “Leningrad: our objective has been achieved. Will now become a subsidiary theatre of affairs.” In line with this strategic thinking Hitler decided to avoid a direct assault on the city and avoid unnecessary casualties. He diverted Panzer units and Luftwaffe formations such as the V111 Air Corps to Army Group Centre for its upcoming attack on Moscow. Field Marshall Leeb, commander of Army Group North, was ordered to lay siege to Leningrad and destroy its inhabitants through a deliberate policy of starvation.

On 27 September Hitler issued the following Fuhrer directive to Army Group North:

The Fuhrer is determined to remove the city of Petersburg from the face of the earth. After the defeat of Soviet Russia there can be no interest in the continued existence of this large urban area. Finland has likewise manifested no interest in the maintenance of the city immediately at its new border. It is intended to encircle the city and level it to the ground by means of artillery bombardment. Requests for surrender resulting from the city’s encirclement will be denied, since the problem of relocating and feeding the population cannot and should not be solved by us.

As the Wehrmacht began to lay siege to Leningrad the towns, villages and small cities that were close by were subjected to a genocidal occupation by German infantry.

The experience of the small city of Pavlovsk was typical of many under Nazi occupation. All those civilians deemed fit for work were forced to work 16 hours a day performing back breaking labour while “daily beatings’’ of these slave labourers were common. Meanwhile, over 6,000 civilians were deported to various labour camps across Northern Russia and some were sent to work as slave labourers in Germany itself. Prisoner of war camps for captured Red Army soldiers were even worse as they also were subjected to the same regime as civilian slave labourers yet given only 28 grams of ersatz bread a day. Not surprisingly, these soldiers died at an alarmingly high rate. At the same time German troops mercilessly destroyed the Jewish community of the town.

As if this wasn’t nightmarish enough German troops began regular public executions of civilians in retaliation for partisan sabotage activity against the Wehrmacht. Jeff Rutherford in his book Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front has observed that German infantry collaborated on a daily basis with members of the Einsatzgruppen in their murderous activities against the civilian population. He further notes that many German soldiers saw Leningrad as the birthplace of Bolshevism and regarded its inhabitants and those in the surrounding areas as especially suspect and undeserving of any mercy.

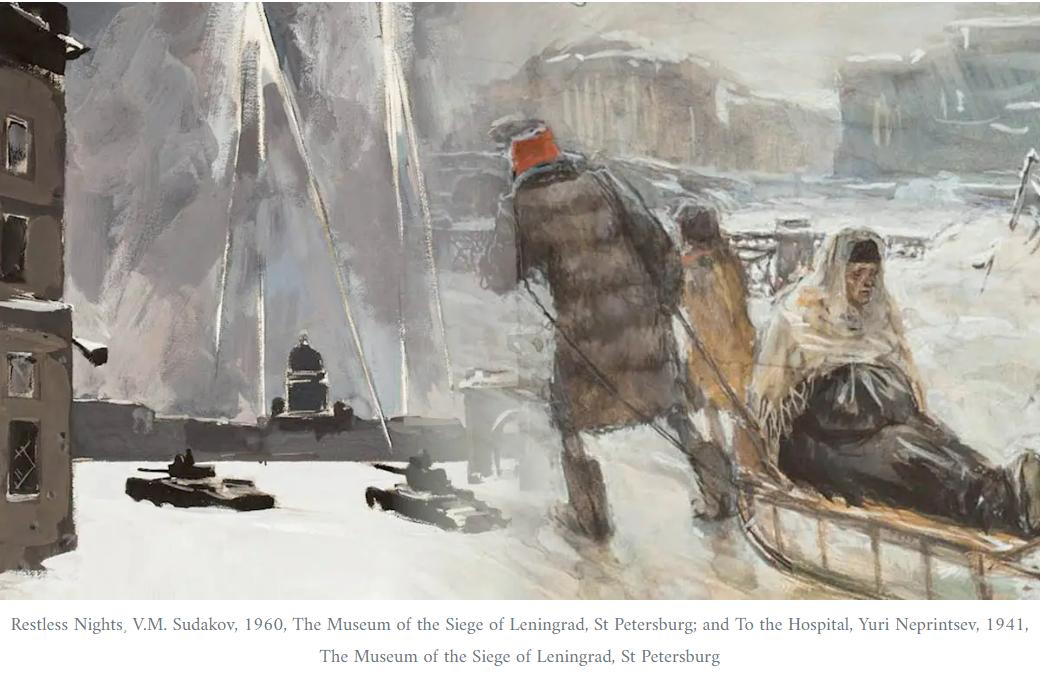

By early September all commercial stores had been closed in Leningrad. There was growing panic amongst the population regarding the food supply. Elena Skrjabina noted in her diary that she would run around the city following rumours of where food might be available to buy, “The whole city was struck with a ‘fever’ to get food: The stores are virtually empty. Everywhere there are enormous queues.… In queues from morning to night.”

In desperation Leningraders went out to the surrounding countryside despite the close proximity of advancing German troops to scavenge vegetables left behind by the rural population which had fled.

The composer Dmitry Shostakovich, a native Leningrader, spoke on Radio Leningrad in an attempt to reassure the panic stricken population:

I completed the score of my large symphonic work. [he started work composing his famous 7th Symphony back in July] Why do I tell you about this? I tell you this so that those who are now listening to me shall know that the life of the city is going on normally...Soviet musicians, my many and dear colleagues, my friends. Remember that our art is threatened with great danger. We will defend our music. We will work with honesty and self sacrifice, that no one may destroy it.

After the broadcast Shostakovich returned to his apartment to continue his work and serve as a volunteer fire warden. As he continued with composing his 7th ‘Leningrad’ symphony he received numerous demands from Moscow that he leave the city. Shostakovich who had a deep love for the city and its people kept refusing. In early October he finally gave in and he was evacuated to Moscow and then Kuibyshev.

The radio address that Shostakovich delivered on 1st September has been preserved. On the back of them are the notes of the studio director. They give an insight into the many tasks, problems and dangers facing the citizens of the city:

Plans for next broadcasts to the city

- Organize detachments

- Communications in the streets

- Construction of barricades

- Fighting with Molotov cocktails

- Defence of houses

- Especially emphasize on all instructional transmissions that the battle is nearing the closest approaches to the city, that over us hangs the deadliest danger.

On the same day the poet Anna Akhmatova spoke over the radio in the evening where she gave a very moving address to a frightened population. Akhmatova said that the Nazis were trying to take prisoner “the city of Peter, the city of Lenin, the city of Pushkin, of Dostoyevsky and Blok, the city of great culture and achievement.”

All my life is connected with Leningrad. In Leningrad I have become a poet. Leningrad gave my poetry its spirit. I, like all of you now, live with one unconquerable belief – that Leningrad never will be fascist.

The people of Leningrad were in grave danger and about to have their lives turned upside down as they entered a 900 day nightmare which pushed human endurance to its utmost limits.

Historian Michael Jones in his book Leningrad State of Siege has observed that in early September 1941 “Leningrad’s system of barricades were badly planned and shoddy. There were only a few feet high. Occasionally a tram was turned over and filled with sand, and some wooden pillboxes were built. For the most part, these emplacements were not manned or equipped with weapons.”

Voroshilov and Zhdanov the hapless and incompetent rulers of the military and civilian population issued a declaration which left many civilians unimpressed:

Let us all arise together. Armed with iron discipline and Bolshevik-style organisation, we will courageously meet the enemy and inflict on him a devastating defeat.

Many felt that the city leadership had no right to call on women and children to throw stones or pour boiling water on invading German troops. The city leadership eroded public confidence in themselves even further by ordering the laying of mines and explosives across the city under bridges, public buildings and factories. One factory worker objected strongly to these measures by saying “And what are we supposed to do after the factories have been blown up? We can’t be without factories – we have to work in order to eat. We will not blow them up.”

Others responded in a more humorous way to the news of the mining of the city. On 7 September Yuri Ryabinkin set out in his diary a ‘Top Secret – plan for the defeat of the German armies surrounding Leningrad.’ It declared: “Act in this way. Mine the whole of Leningrad. Create total panic in the city. Send all the people out into the forest so that Leningrad is empty. Withdraw our troops. No one must understand what the commander-in-chief has in mind. The Germans will enter the city. Unexpectedly, like lightning, we will go over to a general offensive. So much for my dream fantasy. There is of course no one who could undertake a general offensive.”

German army loading shells in a heavy artillery piece

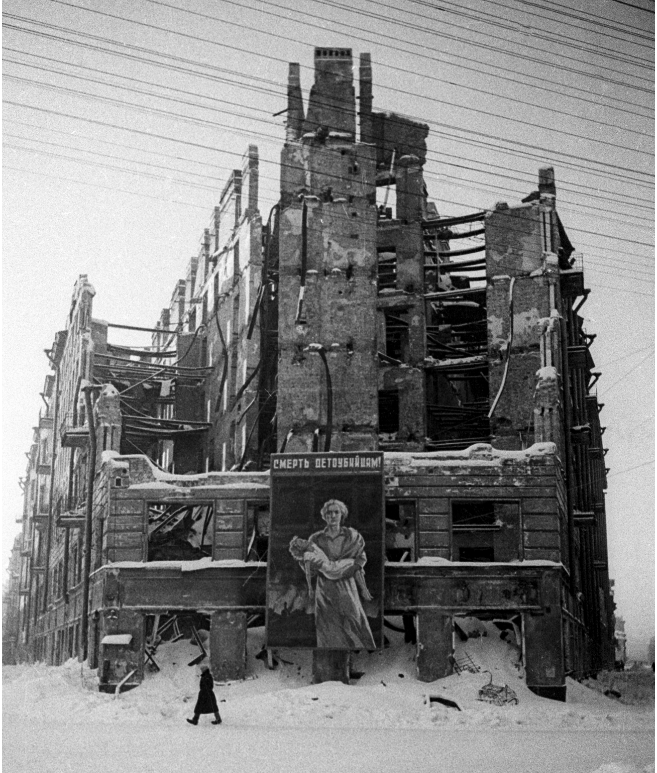

On 4 September German artillery began shelling Leningrad. This soon became a twice daily routine of firing on the city and destroying its critical infrastructure. Two days later the first Luftwaffe bombing raids started which continued until 27 September. During this period there were eleven day and twelve night raids. Then for the rest of the year the Luftwaffe conducted 108 bombing raids. In total German bombing raids on the city during 1941 dropped 67, 078 incendiary bombs and 3925 high explosive bombs which caused 88% of all the casualties Leningrad suffered during from air attack throughout the entire war.

The deadliest bombing raid came on 8 September which destroyed the Badayev warehouses. These wooden warehouses covered several acres in the south west of the city and contained the main food stores of Leningrad. The incompetent leaders of the city Voroshilov and Zhdanov had failed to distribute the precious food supplies across the city instead they left them concentrating all in one place. An act which condemned the people of Leningrad to famine.

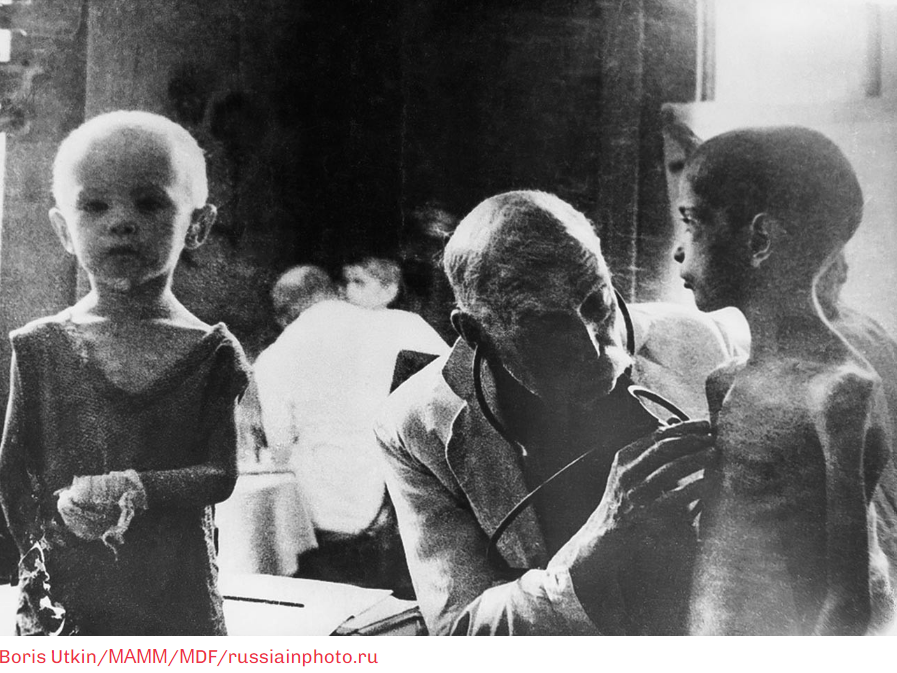

It is worth noting that before this fire on 2 September food rations for the population had been cut. The bread ration was reduced to 600 grams (around a pound a day) for factory workers, 400 grams for office workers and a mere 300 grams for children and the sick and elderly. The meat ration was fixed at 3 pounds of meat per month with cereals to the same level, fats to a pound and sugar to five pounds a month.

In the evening of 8 September sirens blared warning the people of an imminent German bombing raid. The first attack of 27 Junkers dropped 6,327 incendiary bombs which set off 178 fires. At 10.35 pm a second wave of bombers dropped 48 high explosive bombs weighing between 500 and 1,000 pounds. The entire fire fighting apparatus of the city was sent to fight the fire at the Badayev warehouses which took all night to bring under control.

Citizens of Leningrad sheltering from an air-raid

Harrison Salisbury in his book The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad has commented on the impact of this fire on the population of Leningrad:

Not a person in Leningrad on the morning after the Badayev fire had reason any longer to doubt that the city faced the grimmest trial of its history. The smell of burning meat, the acrid stench of carbonized sugar, the heavy scent of burning oil and flour filled the air. Everyone knew Badayev was the city’s greatest warehouse. Everyone knew that here the grain, the sugar, the meat, the lard, and the butter for the city were stored. Now it was lost. ‘Badayev has burned,’ the babushkas said. ‘It’s the end-famine.’

At the Peterhof Palace the leadership of the Leningrad Communist Party were acutely aware of their responsibility for the disaster. N.M. Shekhovtsev, deputy of the City Soviet, arrived at the palace at 6am on 9 September from the scene of the fire. M.V. Basov of the Leningrad Party organization asked him “Has it all burned?”

Shekhovtsev sighed and replied, “It’s burned. We kept all these riches in wooden buildings, practically cheek by jowl. Now we will pay for our heedlessness. It’s a sea of flames. The sugar has flowed into the cellars-two and a half thousands tons.”

He then launched into an angry tirade denouncing himself and the party authorities for their carelessness for not dispersing the food supplies, for the lack of secure buildings and lack of fire fighting equipment.

Bason retorted back: “Well the leaders are to blame - ourselves among them. The people have good grounds for hurling some nasty words at us. What are the people saying?”

“They’re saying nothing,” Shekhovtsev replied. “They’re fighting the fire, trying to save what they can …’’

Following the fire Dmitri Pavlov was dispatched by Stalin to take charge of Leningrad’s food supplies. Pavlov estimated that 3,000 tons of flour and 2,500 tons of sugar had been destroyed in the fires. Of this, about 700 tons of blackened, dirty sugar would be reclaimed and converted into ‘candy.’ He also ordered the remaining flour supplies of the city to be dispersed throughout the city along with the remaining stocks of grain.

The Leningrad authorities responded to this disaster by cutting the food ration further on 11 September. The bread ration for workers was reduced to 500 grams a day, 300 for office workers and 250 for children, the sick and elderly. The ration for children amounted to six thin slices of bread per day. The nutritional content of the bread would soon be degraded as flour supplies dwindled to nothing.

For most Leningraders there was a terrible realization that they and their families faced an impending famine as winter approached. Michael Jones has observed that the citizens of the city responded in different ways to the struggle to stay alive. Tragically, for some panic and fear in the face of hunger destroyed them before death itself did. Other people remained determined to maintain their values regardless of how hungry they became and displayed an incredible willpower and determination to not only survive but to help others at a time of collapse, death and destruction.

Jones has noted that by mid-September the siege of Leningrad was well under way:

It was to be more than a life-or-death struggle. For the city’s two-and-half million trapped inhabitants – faced with the total disintegration of their way of life – this was to be a fight for their very humanity.

Interesting historical post.