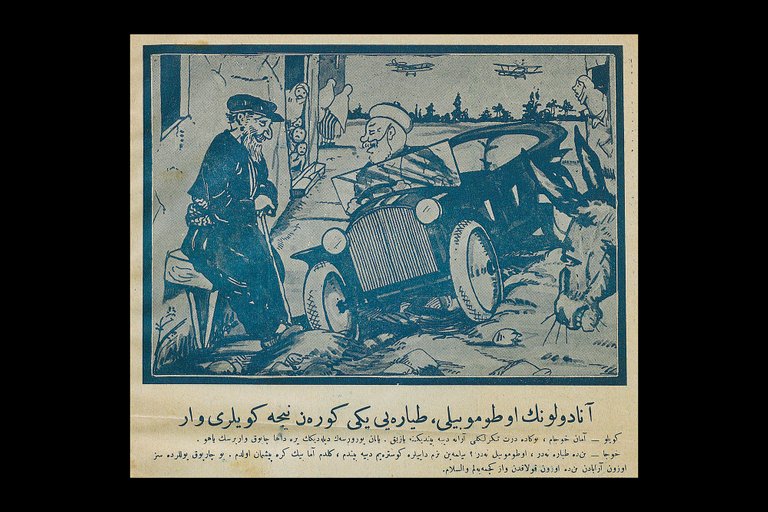

(Illustration, Babacan, 13 August 1928, no. 9, page 4.)

Türkçe

Anadolu’nun Otomobili, Teyyareyi Yeni Gören Nice Kişileri Var

Köylü: Aman hocam, buna da dört tekerlekli araba diye bindiğine yazık. Yayan yürürsen dilediğin yere çabuk varırsın yahu.

Hoca: Bende teyyare nedir, otomobil nedir? Bilmeyen bizim dayılara göstereyim diye bindim, geldim ama bin kere pişman oldum. Bu çarpık yollarda siz uzun arabadan ben de uzun kulakdan vaz geçmeyelim vassalam.

English

Anatolia Has Many People Who Have Only Recently Seen Automobiles, Planes

Villager: It’s a shame that you rode this thing under the assumption it is a four-wheeled car. You could arrive at your destination faster if you walked.

Hodja: What business do I have with planes and automobiles? I just rode this over here to show it to our friends and family who are unfamiliar with it, but now I regret it a thousand times over. Don’t give up your buckboard on these irregular roads, (and) I won’t give up my long-ears, and that’s that.

Comments:

Today’s cartoon illustrates a common problem preventing the early spread of certain modern amenities to the more remote, mountainous, or otherwise inaccessible parts of the country. The imagery shows the Hodja, our protagonist and mascot of the Babacan magazine, behind the wheel of a car that is stuck in the ditch of an unpaved road running through an unidentified village. Representing a typical rural scene, the narrow road is peppered with people: an elderly man leaning against a wall, curious women and children hanging out the doors and window of houses, and a nearby donkey off to the side. Some of these people are looking at the car in the foreground, while others are peering out at the airplanes flying in the skies above.

The elderly man prompts the dialogue with the chauffeur/Hodja in the text below. Here, it is revealed that the Hodja regrets bringing a car to the village, which does not have paved roads. With the roads being so bad, a driver is left with no choice but to drive slowly so as to not harm his ride. And of course, at a slower pace, a car loses its main function of speedy transportation. In the end the Hodja vows to stick to his more traditional mode of transportation from now on: old “long ears,” which refers to his donkey.

There’s a saying, “don’t put the cart before the horse.” The same logic applies here. Like many modern amenities, it only takes some personal funds to purchase, own, and operate an automobile. But if there are no roads to use it on, no skilled mechanics to fix it when it breaks down, no stores to replace broken parts, or no gas stations to fill up on fuel, such an experience is fated for disaster.

Of course, at this time in history, such problems are unique to rural areas where the demand/population for such amenities are less than that of a city. Thus, the “automotive culture” of sprawling metropolises like Istanbul is rather substantial by the late 1920s. Not only were cars visible on every street but demand for cars was such in the 1920s that Istanbul-based journals often included advertisements for automobiles, parts, and services, suggesting a more complete support apparatus for the industry. However, with the emergence of one mode of transportation, other modes become obsolete. For instance, in 1927 oxcarts were banned inside the city limits due to their slow pace. But with great speed comes great responsibility, and the frequent appearance of announcements warning pedestrians to use the sidewalks and stories about numerous traffic accidents paints a picture of a bustling, high-paced city that includes both the benefits and violent drawbacks of modern modes of transportation.

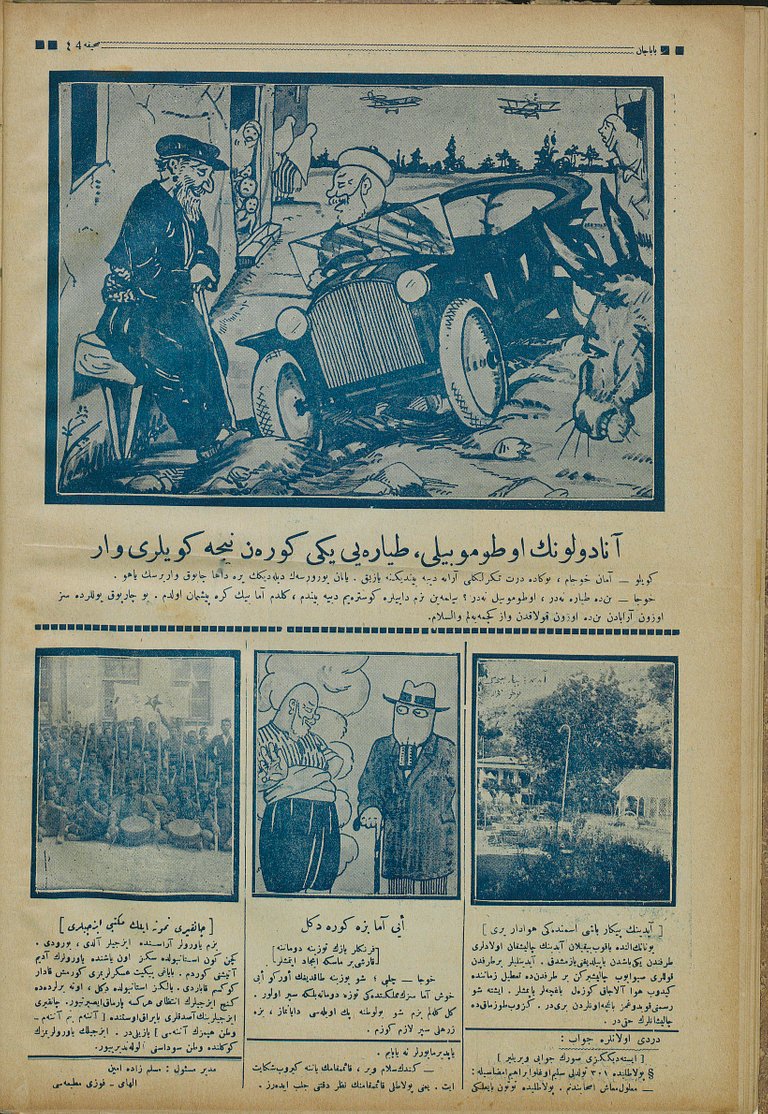

(Entire page, Babacan, 13 August 1928, no. 9, page 4.)