Recruiting spies in high places can be tricky. Potential turncoats must be located, assessed for weakness or disillusionment, befriended, and convinced. The risks are high. Legendary KGB spymaster Arnold Deutsch had a better idea. He would find academically gifted young prodigies with communist sympathies, recruit and train them, and then send them into their careers at the highest levels of government. He played the long game, and the payoff was devastating to British intelligence.

Deutsch was an Austrian agent who was trained in Moscow in 1932 and was posted in France before transferring to London in 1934. He had a PhD and took a postgraduate class at London University, giving him cover to mingle easily in academic circles. He looked to Oxford and Cambridge for his recruits. The first young leftist to catch his eye was a graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge. His name was Kim Philby.

Born on January 1, 1912 in British India, Harold "Kim" Philby (pictured above) was the son of author and Indian Civil Service member St. John Philby. The elder Philby was a convert to Islam and an advisor to King Ibn Sa'ud of Saudi Arabia. Young Kim spent time as a teenager living among the Saudi Bedouin in the desert before attending Westminster School in London. He earned a scholarship to Trinity College, where he graduated with a degree in economics. He then traveled to Austria to aid refugees from Nazi Germany, working for an antifascist communist front group. While in Vienna, he met his first wife, Litzi Friedman, a Jewish communist. He married her and they escaped to London in 1934,

in the midst of rising Nazi terrorism in Vienna. A friend of Litzi's, Edith Tudor Hart, introduced Philby to Arnold Deutsch.

Like most recruits, Philby was not immediately told that he would be working directly for the NKVD (later KGB), but that he would be fighting global fascism. As a lifelong communist, he felt an acute disconnect between his privileged background and the oppressed proletariat that he championed. Deutsch exploited his feelings of hypocrisy. He convinced Philby that by infiltrating bourgeois institutions and destroying them from within, he could accomplish much more than he would by simple activism. Philby dropped out the Communist Party and got busy fitting in with mainstream intelligentsia.

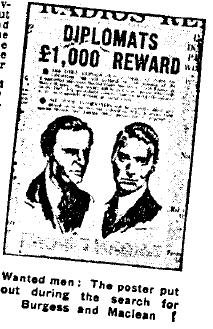

Philby soon brought two recruits to Deutsch's attention: Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess. Maclean (pictured below) was the the son of Sir Donald Maclean, a former cabinet minister. He graduated from Trinity Hall, Cambridge, with first class honors in 1934, and planned on teaching English in the Soviet Union. Philby approached him in August, asking him to work for the NKVD. Maclean accepted his invitation and began preparing for the entrance exam to the Foreign Office. Although he had been open about his membership in the communist party during his undergrad years, he passed the Civil Service boards by dismissing his earlier Marxist sympathies as a youthful phase that he had since outgrown. His academic success, good looks, and family pedigree made a perfect cover for him to infiltrate the British Government.

.jpg)

Guy Burgess, on the other hand, was a less than obvious choice for blending in or keeping secrets. He was an outspoken communist and a flamboyant homosexual (in an era when it was illegal). He was a social butterfly, gracing parties and clubs, where he gossiped and drank excessively. He was in his second year of postgraduate studies at Trinity College when Donald Maclean accidentally let slip his involvement with the communist underground. Burgess desperately wanted in. Philby was concerned about Burgess' erratic behavior, but Deutsch was willing to take a risk with him. Burgess was a fabulous conversationalist who could mingle anywhere, among any class of people. He came from the right background, and had excelled in his education at Eton and Dartmouth. He had an adventurous, willing spirit, and an extensive network of connections. Ironically, his unconventional lifestyle was a sort of cover in itself. Nobody expected someone like him to be a spy.

Donald Maclean entered His Majesty's Diplomatic Service in October of 1935. Later the same year, Guy Burgess became the personal assistant to John Macnamara, a pro-fascist Member of Parliament (MP) who favored friendship with Nazi Germany. Burgess used this temporary posting to gain valuable insight into German foreign policy. In 1937, Burgess became a producer at the BBC. Kim Philby learned Russian while working as a journalist. He also separated from Litzi. In 1937, he went to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War as a correspondent. He also gathered intelligence for both MI6 (British Intelligence) and Soviet Intelligence.

By the end of 1937, the "Three Musketeers," as Philby, Maclean, and Burgess were sometimes called by NKVD insiders, became the "Magnificent Five." Guy Burgess arranged for Duetsch to meet Anthony Blunt, a Trinity College Fellow. Blunt was the son of an Anglican Vicar and was related to the Royal Family. He spoke fluent French and was an art historian. He and Burgess were both members of a secret club called the Cambridge Apostles, whose members were mostly gay Marxists. While teaching at Cambridge, Blunt worked mainly as a talent spotter for potential recruits (until WWII). His most notable conscript was the so-called "Fifth Man", John Cairncross (yet another Trinity College Alumnus).

John Cairncross, unlike the other four men, was Scottish and hailed from a middle class family. He entered Cambridge on a scholarship in 1932, where Anthony Blunt taught his French Literature class. Cairncross was a top student and a gifted linguist, speaking several foreign languages. He graduated with top honors in 1936, and took first place on his civil service exam. He worked briefly in the Cabinet Office before his transfer to the Foreign Office. After a recommendation by Anthony Blunt, he was approached by Guy Burgess to work for Deutsch.

The espionage work of London's Soviet spy network ground to a halt during this period due to Stalin's purges (1936-1938) when so-called "enemies of the people" living abroad were called back to Moscow to be imprisoned or executed. Arnold Deutsch was summoned, but was not executed (the NKVD feared that he had been exposed). Duetsch's successor, Theodore Maly, was not so lucky. He returned to Moscow in 1937, and was executed in 1938. Morale among British spies eroded further when Stalin entered into the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact with Hitler, alienating many anti-fascist communists in their ranks. Contact between the NKVD and the London operation ceased in February of 1940.

By the end of 1940, Trotsky had been assassinated, and most "enemies" had been liquidated from government ranks. Anatoli Veniaminovich Gorsky was dispatched to London to reopen the rezidentura (spy residence within the Soviet Embassy). Gorsky reestablished contact with Philby, who was now working for the British SIS (Secret Intelligence Service) with Guy Burgess. By 1941, the other three were brought back into the fold. Maclean was still working for the Foreign Office. Blunt had entered MI5 (British Security Service). Cairncross, as private secretary to Lord Hankey (a cabinet minister), was able to see and transmit all cabinet papers. Between the five of them, 7,867 classified documents were forwarded to Moscow in 1941 alone, according to KGB archives. Gorsky actually complained that there was too much intelligence to code and transmit, while supervisors in the Soviet Center (Committee for State Security) expressed concerns that the five might be double agents passing along disinformation. The Center's paranoia led Stalin to reject Philby's advanced reports of Germany's impending invasion of Soviet held territories in Poland.

Maclean was by now married to an American woman, Melinda. They had a baby who died shortly after birth. Philby was living with Aileen Furse (they had three children together before marrying in 1946, while she was pregnant with their fourth). Burgess was in a long term relationship with Jack Hewitt.

During the war years Philby worked for Section V of MI6, which handled offensive counterintelligence. He used his position to run agents in Spain, Portugal, North Africa, and Italy. His office was next door to the SIS archives, and he methodically borrowed files, gave them to Gorsky to photograph, then returned them. Burgess continued his career in broadcasting while doing some freelance intelligence work for the SIS. Maclean's Foreign Office files from 1942 encompassed an astonishing forty-five volumes. The Center refused to believe that all of this intelligence contained no evidence of British agents spying in the Kremlin. It was true, though, mostly because MI6 was too busy spying on the Germans. Cairncross spent 1942 and 1943 working at Bletchley Park, where German ciphers were decoded. He smuggled the decoded transcripts to his KGB contact. Through these transcripts, he was able to warn the Soviets about Operation Citadel, an impending German offensive leading to the Battle of Kursk. The Red Army was able to prepare, and the Germans were defeated. The most important wartime intelligence came earlier, though, from the desk of Lord Hankey, via Cairncross in 1941. It involved a secret report concerning an Anglo-American plan for the development of an Atomic Bomb.

In 1944, after corroboration from other sources, the Center finally accepted the fact that the Five were not double agents, and that their intelligence was quite valuable. Philby was awarded a bonus of 100 pounds for his contributions. That same year, he became head of the newly formed Section IX, charged with collecting intelligence on Soviet espionage. Cairncross was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for his intelligence contributing to the Soviet victory against Nazi forces at Kursk. Maclean was transferred to the U.S. embassy, and promoted to first secretary. While there, he continued to advance Soviet knowledge of the Manhattan Project. Burgess took a job in the Foreign Office press department, where he used his influence to pilfer classified documents. He later became personal assistant to Minister of State Hector McNeil. Blunt provided intelligence from MI5, and kept the London Rezidentura abreast of domestic surveillance.

In 1945, Anthony Blunt, coping poorly with his double life, was given permission by the center to leave MI5. He returned to his real passion as an art historian, becoming Surveyor of the King's Pictures. Except for occasional trips to Germany to meet with agent Leo Long, his work for the Center was over.

Philby was promoted to head of British Intelligence in Turkey in 1947. He was responsible for infiltrating agents into the Soviet Union, but the missions he organized kept failing, due to his betrayal of those agents to the Soviets. His most notorious leak involved the Anglo-American collaboration, Operation Valuable in Albania. Albanian commandos were trained in Libya and Malta, then dropped by parachute into Albania where they hoped to overthrow communist leader Enver Hoxha. Many of the insurgents were captured, imprisoned, or shot. The early CIA-SIS covert operation was a deadly failure, and Philby was one of the contributing factors.

During their time in Istanbul, Philby's wife, Aileen, who had a long history of mental illness, was pushed to the edge by Philby's drinking and relentless adultery. After committing serious self-harm, she was sent to a hospital in Switzerland for treatment. Soon afterward, in 1949, Philby was transferred to Washington, D.C. as chief representative of the SIS. He worked as a liaison between the SIS and the CIA, meeting with CIA director James Angleton once a week for lunch. This new posting helped him to betray not only the British, but now the Americans as well.

Meanwhile, back in London, John Cairncross spent the early postwar years at the Treasury, where he was responsible for the authorization of funding for defense research. He was privy to a wealth of information about all kinds of weapons technology, including atomic, radar, aeronautics, and guided missiles. He diligently passed on his findings to the Center.

Guy Burgess was hired for the Information Research Department (IRD) based on his extensive knowledge of Communist subversion. He was beginning to show signs of unraveling during this period. He once dropped a briefcase full of classified documents and had to scramble to collect them from the floor. He showed up for meetings unshaven and hungover. After numerous complaints, he was transferred to the Foreign Office Far Eastern Department within the year, and in 1950, was sent to Washington. Philby let him live at his house, probably hoping to keep him out of trouble.

Donald Maclean was also beginning to fall apart. He was posted in Cairo in 1948, and began to feel isolated and depressed. He wrote the Center in 1949, asking permission to resign. After receiving no reply, he experienced a breakdown, flying into drunken rages and vandalizing property. In 1950, the Foreign Office called him back to London for a leave of absence and psychiatric treatment. Unbelievably, he returned to work the same year and was appointed head of the American desk.

In addition to the alcoholism and emotional problems, the Five faced a new threat: the Venona Project. During World War Two, U.S. Army Signals Intelligence had managed to decode messages intercepted from the NKVD, KGB, and GRU. The project was top secret, but the Soviets were tipped off in 1947. A small panic spread throughout Soviet intelligence, because it was impossible to know which messages had been decoded, and how much of the Center's work was exposed.Through his SIS position, Philby had access to the Venona transcripts, and soon discovered references to an agent code named HOMER. Philby knew right away that HOMER was Donald Maclean. He raised his concern with the Center through his courier, Guy Burgess.

Coincidentally, Burgess' drunken outbursts were reaching a critical point. He was ordered back to London by the Ambassador himself. Philby used this opportunity to have Burgess, upon his return, warn Maclean that he had been identified as a spy. Maclean was reluctant to leave his wife Melinda, who was pregnant with their third child, but was ordered by the Center to defect to Moscow immediately. Burgess was ordered to escort him, under the false premise that he could return to London. In reality, though, the Center was desperate to exfiltrate Burgess, whose outrageous escapades had become a serious liability. On May 25, 1951, Burgess and Maclean boarded a pleasure cruise bound for St. Malo, France. They left the boat and reached Switzerland by train, where the Soviet embassy provided forged passports. They traveled by air to Prague, Czechoslovakia, and finally to Moscow. Back in London, Anthony Blunt searched Burgess' apartment and removed any incriminating documents, or so he thought. A subsequent search by MI5 turned up some handwritten notes from John Cairncross, describing a confidential meeting in 1939. Under questioning, Cairncross admitted to giving information to Burgess, but denied that he was a spy. He resigned from the treasury, and moved with his new wife, Gabriella, to the United States. Anthony Blunt was pressured by the Center to defect to the U.S.S.R., but flatly refused, unwilling to give up his comfortable lifestyle.

The defection of Guy Burgess placed Kim Philby under suspicion, as he had feared. He was sent back to London, where he quietly retired from the SIS. He was subjected to an MI5 inquiry, but was not prosecuted due to lack of evidence. He blamed Burgess, who had earlier promised not to defect with Maclean and thus cast suspicion on Philby. The Center cut off all contact with him. Philby was repeatedly interrogated over the next few years, until he was officially exonerated in 1955. He returned to his old career in journalism, and in 1956, moved to Beirut, Lebanon to become a Middle East correspondent. Incredibly, he also resumed his work for the SIS and, consequently, the KGB. He began an affair with Eleanor Brewer. His wife, Aileen, who had stayed behind in England, was found dead in 1957 of heart failure. Philby married Eleanor in 1959. His drinking and depression steadily worsened over the next few years. In 1961, new information implicating Philby emerged from a KGB defector, Anatoliy Golitsyn. In late 1962, MI6 officer and old friend Nicholas Elliott met with Philby in an attempt to extract a confession. He found him intoxicated with a bandage on his head. He confessed to espionage activities, but would not sign a statement. Philby disappeared on January 23, 1963, having boarded a Soviet Freighter.

The friendships of the Cambridge Five fell apart after their respective retreats. Philby never forgave Burgess for his defection, even though Burgess himself had been tricked into it. When Burgess lay on his deathbed in 1963, he asked his old friend Philby to visit him. Philby refused. Soon after his arrival in Moscow, Philby began an affair with Donald Maclean's wife, Melinda, thereby ending another friendship. John Cairncross, living in the United States and lecturing at Northwestern University, confessed to his espionage activities but denied being part of any spy ring. He also made it known that he had never liked the others, anyway. Blunt was exposed in 1963 by one of his recruits, and made a full confession in 1964. He exposed other spies, including Cairncross. In exchange for his confession, the Government kept his espionage activities a secret (he was finally exposed publicly in 1979 by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher).

Guy Burgess died of arteriosclerosis in August of 1963. Donald Maclean passed away in Moscow in March of 1983, and Anthony Blunt died in London a few weeks later. Philby died in Moscow in 1988 while living with his fourth wife, Rufina.

Cairncross married his second wife, Gayle, shortly before his death in 1995 at the age of 82.

In spite of their treachery, the Cambridge Five captured the public's imagination, inspiring countless movies, plays, and books, most famously John LeCarre's novel, "Tinker, Tailer, Soldier, Spy." Some consider them the impetus for the entire spy thriller genre. Blunt, Philby, and Cairncross wrote memoirs, and new nonfiction about the Five continues to be published at the time of this writing.

The Cambridge Five were responsible for incalculable damage to British Intelligence and credibility. Despite turning over thousands of documents to the KGB, none of the Five were ever prosecuted.

*Citations:

"The Sword and The Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive", Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin: 1999, Basic Books (Perseus Books), NY

"Enemies Within", Richard Davenport-Hines, 2018, HarperCollins, UK

Hello @shawnna.morris! This is a friendly reminder that you have 3000 Partiko Points unclaimed in your Partiko account!

Partiko is a fast and beautiful mobile app for Steem, and it’s the most popular Steem mobile app out there! Download Partiko using the link below and login using SteemConnect to claim your 3000 Partiko points! You can easily convert them into Steem token!

https://partiko.app/referral/partiko

A fascinating story... I’ve always been intrigued by the Cambridge spy ring. Thanks for sharing, @shawnna.morris .

Posted using Partiko iOS

Thanks for reading!