By: Glenn Hodges

Four centuries before Columbus arrived in America, the Indians in Illinois built a town of 15,000 with over 100 hills, and a wide range of influences. What exactly is this place called Cahokia, and what happens to it.

If they opened Wal-Mart in Machu Picchu, I would have thought of Collinsville Road. I stood in the middle of what in the past was the leading civilization between the Mexican desert and the North American Arctic-the first and undeniably American city of America's most fascinating achievements-and I really can not imagine anything worse than a four-lane highway that sliced this historic site. Instead of imagining the thousands of people in the past huddled in the big square here, I am constantly worried about the fact that Cahokia Mounds in Illinois is just one of eight World Heritage sites in the United States, and tainted by Joe's Carpet King billboard in the middle .

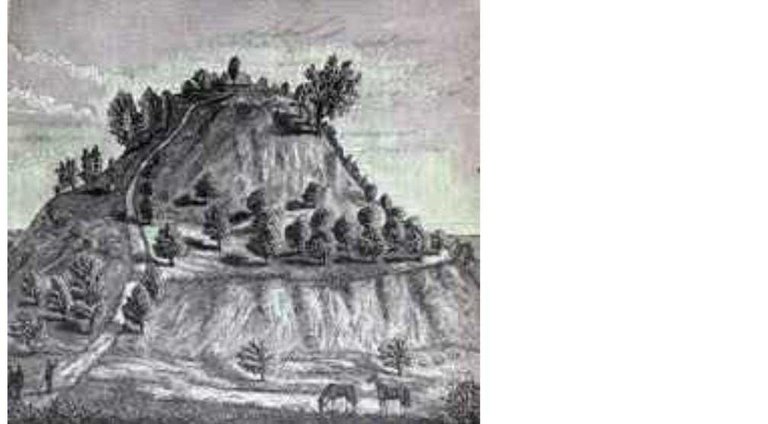

Even so, I think Cahokia's fate is still better. Less than 16 kilometers to the west, an ancient Indian mound that caused St. Louis was nicknamed the City Mound (Mound City) in the 1800s was almost entirely flat at the turn of the century. Today only one survives, along with a number of photographs and a piece of a small street called Mound Street. The massive development of the 20th century had a major impact on Cahokia: The rodent farmers (Armoracia rusticana) leveled the second largest mound for farmland in 1931, and the site was once a gambling place, apartment, airfield, and (adding to the severity of abuse ) porn movie theater. However, most of its important features can survive, and almost all that survive it is now protected. Cahokia Mounds may not have a beautiful appearance, but with an area of 1,600 hectares (890 of which is preserved as a historic site), this site is the largest archaeological site in the United States, and has changed the views of Americans about what the life of Indian tribes on this continent before coming Europeans.

Cahokia

Cahokia is the highest peak, or perhaps origin, culture that anthropologists call the Mississippi culture-a group of peasant societies that spans Central and West America and South-East America, since before 1000 and culminates around the 13th century. The idea that American Indians could build something resembling a city seemed so impossible for immigrants from Europe, so when they found Cahokia's mound-the largest of which was a building of ten-storey land comprising more than 622,970 cubic meters of land-just they thought the city was the work of a foreign civilization: the Phoenix or the Vikings or possibly the lost tribe of Israel. Even now, the idea of an Indian city is so contradictory to American assumptions about Indian life that it seems difficult to accept, and it is probably this denial that makes all Americans ignore Cahokia's presence. Ask the Americans if they ever knew about Cahokia. In casual conversation, it turns out that no American living outside St. Louis who once knew the site.

Ignorance Americans are caused by many reasons history and culture. The first to write about the mound Cahokia in detail is Henry Brackenridge, lawyers and historians amateur find the site and bumps its huge time exploring prairi around on the 1811. "I am very surprised, such as experienced when contemplate the pyramids Egyptians," so he wrote. "This mound amazing! Hoard land as much as it must take many years, and thousands of workers." However, news newspaper on discovery arguably not ignored people. He complained it in a letter to his friend, former President Thomas Jefferson, and thanks to a friend domiciled as high as that's the news about Cahokia is finally spread as well. Unfortunately, the news is not a news by most Americans, including the next President, considered to be interesting. United States middle trying to get rid of the Indian tribe, not appreciate cultural history of them. Law removal Indian (Indian removal Act) passed Andrew Jackson in 1830, which ordered relocation Indian tribe in region East to land in the West Mississippi, based on the view that the Indian tribes tribe nomadic cruel must have been unable to work on the land. Evidence of the city of Indian ancient-city compete with the size of Washington, at the time-must interfere with the views "official" these.

Even a variety of American University was not care about Cahokia and archaeological site other American before the second half of the 20th century. They prefer to send archaeologists them to the Greek and Mexico and Egypt, which is the story of civilization purbanya are in place far and romantic. Handful of people who defend Cahokia and centers mound around in East St. Louis and St. Louis launched resistance arguably failed to the development and waiver for nearly a century. Two site latter-between the community of Mississippi largest-destroyed and be used as the road. And although monks mound, named by pastor (Monk) France ever lived in the shadow, a National Park small in 1925, garden was used to activities sledding with train and hunting Easter eggs. Other parts of the Cahokia generally ignored-built and only occasional studied-up to the 1960s.

It was at this time that history showed the clearest irony, because the greatest development project that would overwhelm Cahokia actually catapulted it as an archaeological site. The interstate highway program proclaimed by President Dwight Eisenhower, though a project that transforms the American landscape as dramatically as the railroads of the past, includes provisions for reviewing archaeological sites on its tracks. This means there is more money available for excavation than ever before, as well as a clear agenda of where to dig, when and how fast. With two highways across the ancient city-I-55/70 now split two plazas north of Cahokia, creating a road flanked by Collinsville Road, half a kilometer to the south-archaeologists began to systematically study the site. Apparently they managed to uncover something extraordinary.

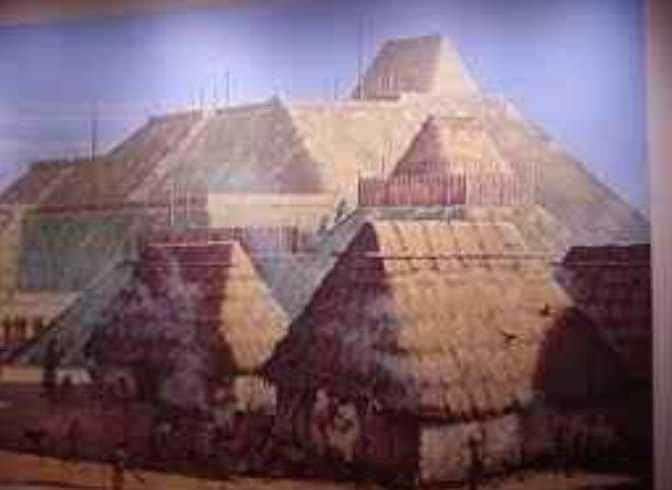

It becomes very clear that Cahokia is more than just a large mound of land or a ceremonial site that is occasionally used to gather by scattered tribes. It may be said that wherever they dug, these archaeologists found the house-indicating that thousands had lived in the community-and many of these houses were built in a very short time. In fact, the whole city seems to be instantly growing in the 1050s, a phenomenon now called the "big bang." People are coming from the surrounding area, building houses, and quickly building new city infrastructure-including a few bumps with buildings on top and squares large area of 37 soccer fields, used for everything from sports games to joint parties to religious ceremonies.

What makes this story more interesting is the strong evidence of human sacrifice. The archaeologist who dug the Mound 72, as they called him, found the remains of a woman's body and a man of very high status, as well as the remains of four unconverted men who may be serving a sentence imposed by some sort of ruling system. This discovery contradicts the prevalent view that American Indians live in egalitarian societies without possessing the kind of rulers who often lead cruelly as in many other civilizations. Is Cahokia a kingdom, like the Mesoamerican civilization in the south? The proof is still inconclusive, but something amazing has happened here, and it is definitely a mystery worth trying to unveil.

If we want to understand Cahokia, the first thing we have to do is climb 156 steps to the top of the Monks Mound. From the flat top of this huge hill-with an area of 5 hectares, essentially wider than the base of the Great Pyramid of Khufu, the largest pyramid in Egypt-we can not only imagine how many workers built it but also understand why it was built. From here we can survey the realm of Cahokia: the vast floodplain known as the American Bottom, stretching from St. Louis to the ridge line that towered five kilometers east of Cahokia and as far as the eye looked north and south. After directing the construction which may be the highest geographic building on a flood plain of 450 square kilometers, a high-ranking leader or pastor has a broad view of the area under his control.

Of course, that scenario assumes we know that Cahokia has a single leader like that, and we do not know. We do not even know what the name of this place is-Cahokia's name was borrowed from the name of a tribe who lived nearby in the 1600s-or the name used by the people living here to call their tribe. In the absence of a written language, they leave behind the same few clues scattered, which make it difficult to understand prehistoric societies everywhere. (Pottery is good evidence, but how far can foreign cultures really study us by just looking at our food?) If uncovering a history story is debatable, let alone reach agreement on prehistoric stories. "You must know what they say," said Bill Iseminger, an archaeologist who has worked with Cahokia for 40 years. "Gather three archaeologists in one room, then we will get five opinions."

Iseminger is not excessive. Even when the Cahokia researchers agreed, they tended to make up their minds as if they were at odds-but there were several mutually agreed aspects. All of them agree that Cahokia developed rapidly in the centuries after corn became an important part of the local diet, that it collects people from American Bottom, and that dwarfs other communities in Mississippi, both in size and in scope. Differences of opinion tend to be around the question of how much the population of the city, how centralized political power and economic management, and the nature and extent of its reach and influence.

At one extreme, we find an explanation of Cahokia as a "center of power," a hegemonic kingdom sustained by power that penetrates deeply into the Mississippi region and may have something to do with Mesoamerican civilizations like Maya or Toltec. At the other extreme, we get the distinctive feature of Cahokia as a city just a little bigger than the big city in the Misssissippi area where the inhabitants are fond of making high mounds of earth. However, as always, the correct opinion lies between the two extremes.

The discussion is now led by Tim Pauketat at Illinois University, who with his colleague Tom Emerson argues that Cahokia's evolution theory is a visionary product: a leader, prophet, or group proposes a new community structure for Indian life, drawing people from far away and close, creating a cultural movement that is rapidly spreading.

When I met with Pauketat in Cohakia to see the site through his guidance, he was more interested in showing his findings on the plateau, a few kilometers to the east: a sign that Cahokia occupied the neighborhood workers who supplied food to the city and its rulers-evidence , according to Pauketat, that Cahokia's political economic power is centralized and wide-reaching. This is a controversial theory, because the research that supports it is still unpublished, and because it raises the question of what exactly Cahokia society was at that time.

Gayle Fritz from Washington University in St. Louis Louis says that if Cahokia is a city, it is not the city as it usually is in our minds, but a city laden with farmers who grow their own food in the surrounding fields. Otherwise, there must be more signs of food storage. The practical limit of the size of this subsistence-based farming society has led to minimalists such as George Milner of Penn State University arguing that Cahokia's population estimate-currently ranges between 10,000 and 15,000 for its own city and 20,000 to 30,000 in the surrounding area-multiplied by two or several folds , and the assumption that Cahokia is a country is an exaggeration. However, since less than one percent of the newly excavated Cahokia area, more speculation, and not evidence, is advanced by any group that believes in a particular theory. John Kelly of Washington University, an archaeologist who had long studied Cahokia summed up Cahokia's understanding with sweetness: "We do not yet know for sure what the true facts about Cahokia are."

Similarly, we do not know what happened to him. Cahokia was a dead city when Columbus landed in the New World, and American Bottom and most of the Mississippi River Basin and the Ohio River were so few inhabitants that it was called the Vacant Quarter. Cahokia's death may be a greater mystery than its appearance, but there are some clues. The city grew especially during the lucrative climate phase, and began to shrink as the climate became colder, drier, and more difficult to forecast. For peasant societies that depend on regular produce, the changing conditions have a variety of effects, ranging from mild to very severe.

The fact that between 1175 and 1275 residents of Cahokia built-and rebuilt, several times-the bastion of fortifications surrounding the main part of the city implying a dispute or threat of contention has become a habit of living in the region, possibly due to limited resources. Furthermore, the dense population creates continuous environmental problems-forest destruction, erosion, pollution, disease-which can be difficult to overcome and which have been the cause of the extinction of civilizations in the world.

It is not surprising that Cahokia survived for only about 300 years, and was at the top of its power for at least half of that period. "If we look at human history with large glasses, failure is something common," says Tom Emerson. "What's amazing is when there is a lasting social order."

Emerson currently leads a large dig in an adjacent area (like Bogor and Jakarta) with the so-called East St. Louis at the time of Cahokia, a site whose population alone amounted to thousands of people. And as previously said, road construction closes the cost of the excavation: The new bridge across Mississippi gave the Emerson team a chance to explore 14 hectares of land that had previously been declared unusable due to a road construction project. The cattle shed built on the ruins of the Mississippi settlement has been closed for years, the victims of the decline of East St. Louis from the once-crowded city became a collection of abandoned land and buildings whose doors and windows were covered with planks to prevent criminals or squatters from entering. This is the journey of history in the present: so fast moving that it is not easily recognizable.

When I drive to St. Louis to see if there is still something that implies a large mound (named by a no-inventive society to find a better name) that was destroyed there in 1869, I was shocked to see the exact location turned out to be on land where the new bridge span will end from St. Louis. I asked the people around the site and it turns out that archaeologists have dug this field before construction begins. But they found no traces of the Big Mound, only the ruins of a 19th-century factory built there. That is what is now the history of the site. The rest no longer exists.

After the first attempt failed, I finally managed to find the Big Mound identifier. It was a gravel stone monument about half a block from Mound Street to Broadway, with no placards, and grass growing among the pebbles. Thank goodness I found it just before a man came to spray it with a weed killer. I asked him if he was working for the city administration, and he said no. His name is Gary Zigrang, and he has a building some distance away. He had already contacted the city authorities about the damaged identification, but no response whatsoever, so he finally initiated his own handling. And when he sprayed the weeds on forgotten monuments that marked the forgotten mound of forgotten men who had lived there, he said, "It's sad. There is history here, and it should be taken care of. "

Here's what I can say in my post this time, I hope you like and interested in my post.