I admit, I’ve never worn a bikini in my life. I have nothing against them. I just hate being damp and cold. Thus, being damp and cold and nearer-my-God-to-nudity would constitute considerable summertime sadness for me.

While I may not be kini-ing, I would never begrudge someone else (who is better able to regulate their core body temperature) the experience. After all, the frisky fabric has been part of our cultural fabric for centuries. The concept of bathing attire that boldly strays from the full coverage, one-piece-suit variety dates back to at least the fourth century BC. At first blush it may seem like a thoroughly modern concept, but being scantily-clad aligns pretty consistently with the preference of our human nature about as far back as you can go. Beyond that, proposing fashion should have form and function isn’t new, either— and that’s more the spirit of the garment’s origin story.

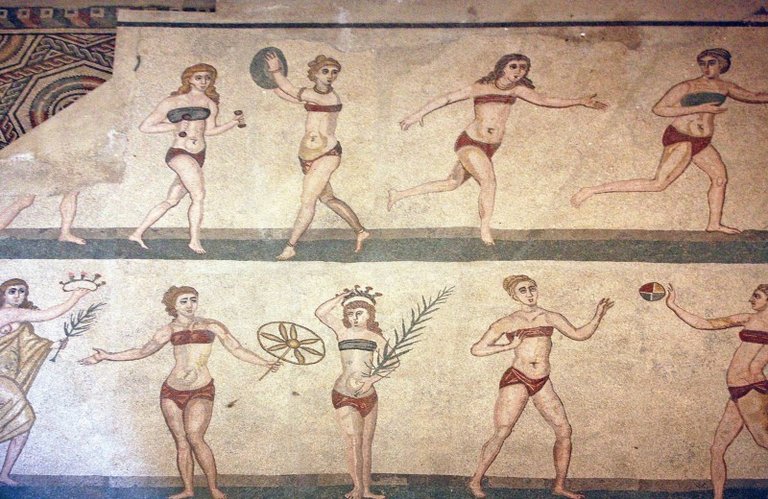

The modern bikini may be viewed through a specific cultural (and hyper-sexualized) lens, but the impetus to design swimwear for women that used less fabric has very practical roots. Ancient Roman mosaics depict athletic women outfitted in bandeau tops and bikini bottoms, which would have been a considerably more practical alternative to the traditional (read: cumbersome) drapery they spent the majority of their time in.

Though, you could add an entire layer of complexity to disc-throwing if you forced people to do it in a Toga.

Roman women playing at sports. Mosaic at the Villa Romana del Casale near Piazza Armerina in Sicily

The sporty get-up fulfilled its function, but that’s not to say it was necessarily more comfortable: the tops were, after all, meant to restrict breast movement — you may envision them as being the sports bra of antiquity. These breath-stealing bands of fabric were already quite familiar to women, though they were typically worn under a garment much the same way bras are worn today.

Bottoms, however, were another matter. The briefs were called subligaculum or subligar; “little binding underneath”(a phrase which, to me, inexplicably conjures up a Katy Perry lyric, but I digress). These underthings were often worn on their own, wrapped loincloth-style, though only ever by two groups of Romans: those engaging in sport —or slaves. In other words, you wore the garb out of necessity — or because you were being forced to. Not because you were vying to be Constantinople’s Next Top Model.

The barely-there bathing suit as a fashion statement would come later. Much later. Only after several centuries of covering women up in so many layers that, by the 20th century, not only had ladies’ beachwear entered into head-to-toe coverage territory, but covered-wagon, horse-drawn carts were employed at public beaches to take women to the water’s edge. This was so they would be viewed as minimally as possible by other beachgoers until they were fully submerged, the sea effectively concealing their aphroditic forms and perhaps cleansing them of sin. A salty twofer.

“Bathing machines,” as these contraptions were known, were just one of many extravagant attempts to hide a woman’s body from public view. Though as the century wore on, it was once again a squad of women who wanted to fully engage in athletics who said, ENOUGH OF THIS ILLIBERAL BULLSHIT!

One lady in particular was particularly well-suited to the task of leading the charge, as she already had achieved a modicum of fame from movies — many of which were, perhaps, a bit cheeky by the standards of the early 1900s. You might say she’d already made something of a literal and metaphorical splash.

Undated photo of Annette Kellerman, but probably late 1900s or early 1910s. Library of Congress.

In 1907, Australian swimmer-slash-vaudeville star Annette Kellerman was arrested for indecent exposure. After she’d disrupted polite society by casting aside her pantaloons and opting instead of a more form-fitting (but still complete-coverage) one-piece swimsuit, her infamous day at the beach became a rallying cry.

Though, she was not necessarily trying to become the poster-girl for freeing one’s beach body. Her reason for ditching the pantaloons for a one-piece was very simple: it was fucking easier to swim in. Frankly, everything about pantaloons, or bathing costumes, or whatever other nonsense was routinely dictated by the puritanical mindset of the era, was the antithesis of hydrodynamic.

As previously alluded to, Kellerman likely had few if any reservations about acquiring a few smudges on her record — or even a full-blown ~reputation. For one thing, she’d already been ascribed notoriety for being the first major actress to appear nude in a Hollywood film. In other words, her bad-ass-bitch-on-the-beach schtick was exactly the kind of shenanigans the world already expected her to get up to.

What was unexpected was the response of women who were not known for appearing in films with adults and/or aquatic themes. As it so happened, “regular” women took to Kellerman’s sleek swimwear design like fish to free and easy water. The joke was on the world: Kellerman added “designer” to her resume and her swimsuit concept, as well as the wellness advocacy it laid the groundwork for, would define the remainder of her life and legacy.

Edith Roberts lying on beach, facing right; publicity shot for a Mack Sennett Production. Library of Congress c. 1918

Looking back at the Hollywood starlets of the early 40s, you’ll see plenty of romping, fun-in-the-sun, beach-babe photoshoots. A young Ava Gardner, Hedy Lamarr, Rita Hayworth, and Joan Crawford all had their turn at what they may have later cringed at and referred to as “cheesecake” shoots. The shoots were more cutesy than carnal — definitely pretty tame by today’s standards: the starlets were photographed wearing a variety of form-fitting one piece or occasionally two-piece suits.

Though, these early two-piece suits were very much not bikinis. They had plenty of coverage. More specifically, they did not allow the belly button to be shown. Cultural and Hollywood standards at the time dictated the navel was the proverbial line in the sand of obscenity. And so, the most you’d get a glimpse of would be the occasion visible spans of ribcage and skin between the top and the bottom of the suit (which, incidentally, is reminiscent of a style that we called a “tankini” back in my day. I recall it as being what pre-teens would wear before they were old enough to graduate to the inherently more sensual bikini).

Meanwhile, in Europe, WWI was approaching and fashion designers (and everyone else, really) were beginning to struggle under the duress of rationing. During WII, just about anything and everything you loved or could possibly want or need was in short supply. French design houses in particular began to realize they would need to make do with a lot less variety, but also materials, in terms of fabric. This would prove to be as much a design problem to be solved by scientists as arTISTS.

Enter two men (ugh): an engineer named Louis Réard (who I would say would become known as “The Father of the Bikini” but I kind of hate how that sounds) and Jacques Heim. Heim, who was a designer by trade, technically created his scanty bathing suit first. His contribution, in fact, is often lumped together with Réard’s — though both men are credited. Ultimately, it was the name Réard gave to his thready threads that stuck.

Both Heim and Réard envisioned their creation as being meant for the blonde beach bombshells of the era. Thus, when they were trying to figure out what to call the suits, they both took cues from another bomb of the era: the atomic bomb. More specifically, the nuclear test site Bikini Atoll.

Heim called his little fabric slice the Atome. Réard went with bikini — which is, of course, the moniker that caught on.

It wasn’t an immediate domination, though. Heim and Réard actually ended up embroiled in a bit of a publicity stunt war. As the story goes, Heim had hired skywriters to fly over a Mediterranean resort advertising his Atome as “the world’s smallest bathing suit.”

Réard responded by hiring skywriters of his own some three weeks later, instructing them to fly over the French Riviera advertising his bikini as being “smaller than the smallest bathing suit in the world.”

That Réard ultimately prevailed is probably due, at least in part, to the fact that he did a bang-up job in terms of timing the suit’s reveal. The “bikini” debuted in France on July 5th, 1946 — just four days after the U.S. started testing at Bikini Atoll. Obviously this was 1946 and we can be sure he didn’t care about “trending hashtags” but damn if his SEO strategy wasn’t on point with that marketing campaign.

Even without Twitter or Instagram, the bikini trended around the world — though not explicitly as a result of its name. That the debut happened at all was more than scandalous; it was also rather impressive. Réard had run into quite a problem in the weeks leading up to the unveiling. Within the fashion crowd, his design was deemed so controversial — maybe even bordering on trashy —that he couldn’t convince a single model to walk in it.

In the end, he’d hired an 18-year-old nude dancer at the Casino de Paris named Micheline Bernardini. She was already quite well known within the circles that would have known about dance hall girls, but after photographs of her wearing Réard’s bikini spread around the world, she and her navel had to contend with a whole new level of fame. In the first weeks after the photographs ran she and Réard received over 50,000 fan letters.

Wiki Commons & Giphy.

Initially, naysaying Americans weren’t that worried about the bikini becoming a thing on their wholesome soil. It was incorrectly assumed that no self-respecting, all-American, girl-next-door woman would be caught dead in something as le sleazy as a French bikini.

But au contraire! Over the course of the next decade, as America became keyed up about family values and Fiestaware, youth who did not want to live the life prescribed to them by society and their parents, and who had perhaps been somewhat empowered by their war efforts the decade before, ate up the cool vibes the bikini aesthetic was serving.

Eventually, attitudes began to calm: by the mid-1950s, the bikini received the Vogue seal of approval. The magazine declared the minimal ensemble had become “more a state of dress than undress.”

There was not universal acceptance of the bikini, though. In 1951, the first Miss World contest spiraled into controversy when its winner, Miss Sweden, was crowned in her bikini. The more conservative and religiously-devout nations of the world. Pope Pius XII publicly vilified bikinis, denouncing them as sin. Though I’m not sure if he took issue with the entire Miss World competition or just the swimwear component. In any case, Kiki Håkansson was both the first and the last Miss World winner to be crowned wearing her itsy-bitsy, teeny-weeny, I’ve-put-off-the-Pope bikini.

The turning point for the suit would come soon enough. The following year, Brigitte Bardot was photographed in a bikini at Cannes (Bardot went ont to adopt this as, like, her thing) it made the bikini’s appeal undeniable.

While it was a bit slow to rise, the market for tiny beachwear began to take off even without the Pope’s blessing. Although well into the late 1960s there were beaches in the U.S. known to hand out citations for bikini-wearing, which was not all that dissimilar to Kellerman’s indecent exposure summons several decades before.

Sports Illustrated via the Internet Archive

Today, the bikini is a familiar and far more accepted presence in the realm of summer fashion. For some, it may even mark a right of passage in one’s feminine identity and emerging sexuality.

Over the last few decades, the bikini inevitably became associated with female caricatures like Bond girls and bodacious beach babes. But it also became emblematic of the very real and sexually-liberated women of the feminist movement.

Clothing has long been an avenue through which individuals, especially women or those who identify and present as, can confidently assert their sexuality and publicly own it. How they’re received says a lot more about what the world sees than what the woman has chosen to show.

But revelation without shame may be where the bikini’s true power lies. After all, within a generation, bikini-clad supermodels weren’t just on the cover of magazines — there were entire magazines devoted to them.

Yes, part of that was the result of the inevitable sexual objectification of said models, but our relationship to the bikini has come a long way. Just a few decades ago, Réard couldn’t get even the hottest of hot couture Parisian models to don one. Fast forward to the 1980s and beyond and models would be clamoring to make the cover of the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue. Bikinis would become a staple at pool parties and beach bashes around the world. It was precisely the fact that they had become so ubiquitous, that no longer an eye was bat, that even in the face of ongoing objectification, it retained some of the personal power felt by Annette Kellerman and Micheline Bernardini. Women who bravely bared what no woman had bared before, and by her own choosing.

French fashion historian Olivier Saillard once said the bikini endures because of “the power of women, and not the power of fashion,” and that “the emancipation of swimwear has always been linked to the emancipation of women.”

To the latter point, in today’s world it often feels as though we are disconcertingly moving backwards. Women in America, and around the world, are suiting up for battle, fighting for rights that we long ago won. Rights that are, in many cases, of greater consequence than wearing a two-piece swimsuit on a public beach. Or are they?

However inconsequential it may seem on the surface, the bikini represents a fight for the female body that we won. Perhaps there’s some reassurance to be found in its persistence. Or, since money talks, even its earning power: by the early 2000s, the iconic swimwear was bringing in $811 million a year.

A symbol of liberation it may be, but in terms of the age-old question of fashion versus function, it turns out the modern bikini may have strayed a bit from its practical predecessor: according to one survey, 85 percent of the bikinis sold every year never get wet.

But maybe they weren’t really about swimming after all.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://medium.com/@abbymnorman/the-ancient-atomic-advocating-history-of-the-bikini-1c84daf9fd62