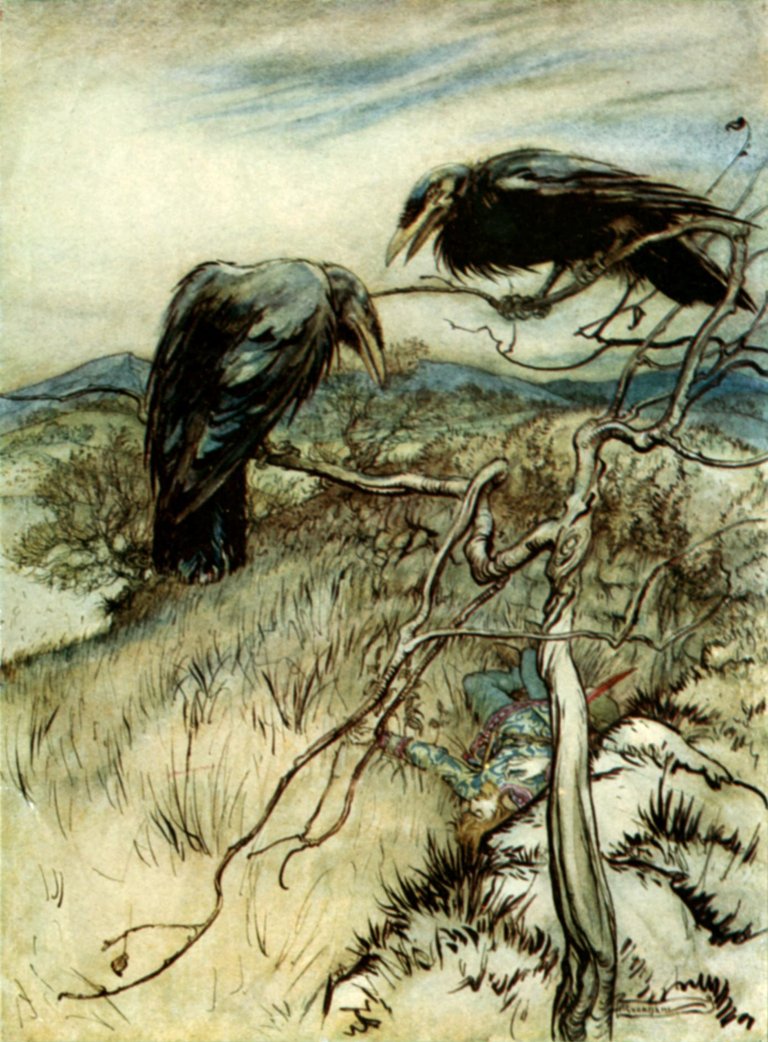

(“The Twa Corbies", Illustration by Arthur Rackham to Some British Ballads, from  )

)

Preparing My Performance

My first big challenge in building a performance version of "Three Ravens," is that the piece contained in the "Melismata" collection is set as a 4-part madrigal, and I am a soloist. After examining arrangements of "Three Ravens" and comparing them, it appears that madrigals of the time could be performed as a solos simply by singing the top line, or melody, with the rest being filled in by instrumental accompaniment (as further documented by McGee on page 105), akin to early folk music.

Given my living history/historical performance persona's status (5), it was important to me to preserve the “folk song” aspect of it – solo with bare accompaniment – in addition to working within my limitations as a performer. Typically, according to McGee, the accompaniment would condense the supporting lines in the madrigal. Due to the difficulties of condensing parts and playing multiple lines that sometimes are at odds against the melody, I chose a version (from Powers’) that contained chords for ease of interpretation. Studying the alto, tenor, and bass lines in the madrigal notation, as well as listening to some vocal ensembles (Lumina) perform this piece gave me a better sense of how the accompaniment should support the vocal line.

The next question in my mind was how accompaniment was structured. Traditionally, any accompaniment would have most likely been played on a lute or virginal (6). During this time of history, having such an instrument was a mark of status, as even then they were expensive (7).

While I do not have an authentic lute, one of my primary instruments is guitar, which is in the same family (plucked strings), and can be used to mimic the appropriate sound with the judicious use of playing technique. The Lute Society out of London, UK, has a few beginners' lessons available for free off their website that sufficed as a quick introduction to how a lute is played. Upon researching the technique, it appeared that while the hand and arm positions differed (I would presume to say because of the giant bowled back of the lute), many of the results for playing chords -- plucking the notes simultaneously and/or "spreading" the notes, with a "rolling" motion -- were similar to classical guitar technique.

Using and understanding the Lute Society's information on how to play chords in different styles to further the musical effect enhanced my performance; the ability to either arpeggiate the chord, to "roll" it quickly, or pluck all the notes simultaneously (or any combination thereof), lends a nice bit of variety for the ear. As I practiced, I found myself using the different styles to help enhance the lyric and the story: the first verse begins softly and contemplative, and builds and builds through the subsequent verses until it reaches the climax of the story -- "And she was dead herself 'ere even-song time" -- at which point it returns to a quiet and contemplative state as the narrator tells us how loyalty can earn us much in life and death.

"Three Ravens" presented another problem: the performance length of the song. Traditionally, this early ballad has ten verses and playing at a moderate tempo clocks in over five minutes. (And that was at quite a clip for the tenor and tone of the lyric!) Unfortunately, this length is unacceptable for the modern ear. In Livingston Taylor's book, Stage Performance, (for one example, there are others) he makes mention of the needs of the listener and how the performer's first duty is to their audience. Over time, the average length of songs have shortened -- today, even a three-minute song is considered pushing it. Longer songs risk losing the audience's attention, especially if they are high on repetition. Considering the needs of today's listener (a shorter song), and the importance of telling the entire story of the ballad (i.e. not omitting a single verse), I began to look into ways I could shorten the playing time, yet still keep the ballad intact8. My initial idea was to remove some of the "down adowne" refrains, as they add nothing to the tale, however, that produced a musically ungainly phrase. I considered "splicing" two verses together, for example:

(verse 1)

There were three ravens sat on a tree / Down adown hey down hey down

There were three ravens sat on a tree With a down

There were three ravens sat on a tree / They were as black as they might be / With a down, derrie derrie derrie down down

(verse 2)

One of them said to his mate /Down adown hey down hey down

One of them said to his mate With a down

One of them said to his mate / Where shall we our breakfast take? / With a down, derrie derrie derrie down down

Which became:

There were three ravens sat on a tree / Down adown hey down hey down

They were as black as they might be With a down

One of them said to his mate / Where shall we our breakfast take? / With a down, derrie derrie derrie down down

(&etc.)

At which point I came across a version of lyric at the Cantaria Folk Song Archive that did just what I interpreted, effectively cutting the performance time to just under three minutes -- well within the modern listener's tolerance. I still opted to keep the first and last verses as originally written to honor both the feel and heritage of the lyric.

Conclusion: Pulling It All Together

My desire in presenting "The Three Ravens" in an appropriate manner as possible was to further explore Emma's world. As I practiced, the music taught me things. I had to up my game in terms of guitar skills and really tune into what the music told me, and learning to do what it required. I had to focus on the lyric to convey what it said about the nature of love, life, and death in order to sing it with the inflection at the right places.

Through the process I learned something else, too: that we are really not that different from our historical counterparts.

Our hearts are made of the same things, and that's not something centuries can change.

The birds in "Three Ravens" view a woman who struggles to give her love the honor of a burial and then lies down, broken-hearted, at his side, just as we fall apart when a loved one passes. The mood of the song places us very strongly in that foggy meadow with the birds in the tree, and we are not asked to fear death, we are asked to take a good look at ourselves and how we are living our lives:

Will we be the honorable knight?

Or will we be the carrion that the ravens (presumably) find to feast on later?

—————

5 While Emma is a member of the wealthier middle class, she is far from being a noble. She is a woman who still has to work to maintain the household, and occasionally help her husband with his business. Though she is musically sharp and passionate about her art, she is far from being a virtuoso.

6 McGee references these for their ability to play multiple lines of music at the same time, thereby lending depth to the performance. In his suggestions on page 105, he specifically mentions the harpsichord instead of the virginal, however, a quick Google search produced the information that a virginal was indeed an early form of harpsichord.

7 Today, a basic lute costs around $3000.00, which is, alas, well out of the budget for your average musician.

8 McGee discusses the concessions that must be made regarding texts of early music on pages 109 and 110 of his book, and gives many potential solutions to the problem: omitting repeated parts, omitting unnecessary verses, etc., within the framework of staying true to the text.

Resources

-Brown, Meg Lota and McBride, Kari Boyd, Eds. Women's Roles in the Renaissance. Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing, 2005.

-Cantaria Folk Song Archive. "The Three Ravens." http://chivalry.com/cantaria/lyrics/three-ravens.html. Accessed 4 January 2014.

-Child, Francis James. "Child 26: Three Ravens." http://www.springthyme.co.uk/ballads/balladtexts/26_ThreeRavens.html. Accessed 1 Oct 2013.

-Powers, Courtney Allen and ed. Van der Vliet, Charrie. "Chapter 13: The Three Ravens." 30 Elizabethan Songs – With Documentation. 2008. http://charric.110mb.com/magic/magicmusicfortheweb/13-threeravens.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2013.

“Leman.” Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. 10th ed. Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, Inc., 2000.

-Lumina Vocal Ensemble. "Three Ravens by Thomas Ravenscroft." YouTube, 2013.

-Lute Society of London. "Beginners' Lessons." http://www.lutesociety.org/pages/beginners. Accessed 27 Dec 2013.

-Machlis, Joseph and Forney, Kristine, eds. “Renaissance Sacred Music” The Enjoyment of Music, Ninth. 9th ed. New York: Norton & Company, 2003.

-McGee, Timothy J. Medieval and Renaissance Music: A Performer's Guide. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1985.

-Ravenscroft, Thomas. "The Three Ravens." Melismata. 1611. Ed. Jurgen Knuth. IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library, 27 Oct 2011. http://imslp.org/wiki/The_Three_Ravens_(Ravenscroft,Thomas). Accessed 22 Sept 2013.

-Ravenscroft, Thomas. "The Three Ravens." Melismata. 1611. Ed. Jurgen Knuth. http://imslp.org/wiki/Melismata(Ravenscroft,_Thomas). Accessed 22 Sept 2013.

-Reese, Gustave. Music in the Renaissance. New York: Norton & Company, 1959.

-Taylor, Livingston. Stage Performance. New York: Pocket Books, 2000.

-Waldron, Jason. Progressive Classical Guitar Method: Book 1. South Australia: Koala Publications, 2000.

Beautiful!

Thank you so much for this. More please.

Thank you! I plan on it! :)

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://heatherthebard.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/kingdom-bardic-3ravens.pdf