The unbelievable story of the English prisoner of war Denis Avey, who entered Auschwitz to tell the world - and then remained silent for more than sixty years because he could not find words for what he had seen.

The prisoner band plays Richard Wagner, of all people, when Denis Avey marches in the middle of the prisoner's prison to the Buna / Monowitz concentration camp. At the camp entrance a dead inmate hangs from a gallows. To frighten. Denis Avey walks on and tries not to attract attention: he walks the stooped corridor of the concentration camp prisoners, he looks down, he pretends coughing fits in case an SS man approaches him and he has to hide his English accent. Avey, who is interned as a prisoner of war in a nearby camp, has exchanged uniforms with a concentration camp inmate in order to sneak into concentration camp. If the Germans noticed that, it would be his end.

On an open space in the concentration camp, the prisoners have to stand up, SS men count them off. The evening call lasts almost two hours. Then Avey goes with the prisoners into one of the barracks, past the women's shelter, the camp brothel, in which mainly Polish prostitutes must be willing to non-Jewish inmates. In the barracks, where Avey will sleep this night, three-storey bunk beds, in which the prisoners usually lie in threes on a bunk, are placed head to head. Some use the metal soup bowls as pillows so nobody will steal them.

Denis Avey lies in the middle of a bunk, between two prisoners, and asks what they know about the rumors of gas chambers and crematoria, and the names of SS men and kapos - the prisoners who work as overseers. As the two fall asleep exhausted, Avey remains awake. He tries to memorize everything around him and he listens to the sounds of the night: the crazy ones talking to themselves, the sick moaning in pain and the sleeping ones screaming in their nightmares. That's how Denis Aveys tells his story. Of course, nearly 70 years later, the idea of someone sneaking into a concentration camp during the Nazi period, and thus voluntarily moving to one of these places of absolute terror, seems incredible. Especially as the Buna / Monowitz concentration camp belonged to the Auschwitz camp complex,

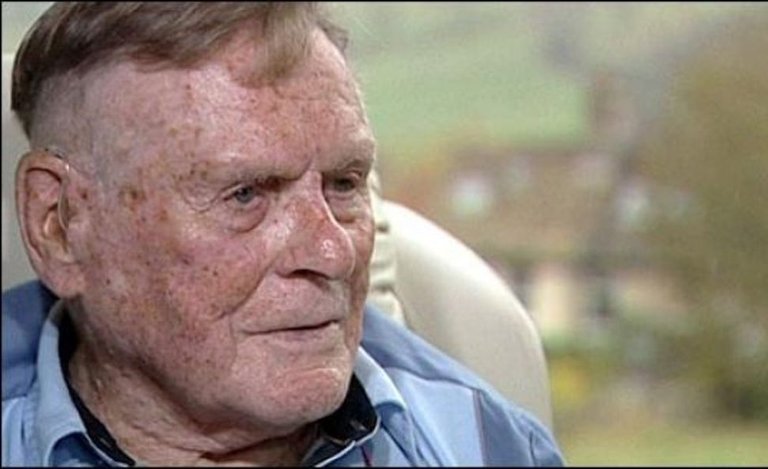

Today, Denis Avey, now ninety-two, sees a similar story: "It was ridiculous, absolutely ridiculous," he says in a BBC interview, "nobody would believe anyone would come up with that idea." In fact, there are doubters, the Aveys Role reversal is highly unlikely, especially as Avey has no evidence. However, most of those who have dealt with his story believe him because what he says is coherent and largely in line with what is known about the concentration camps today.

On top of that, Avey did not sell his story exclusively to a revolver sheet - which would rather make him suspect that he wanted to draw attention, fame and money - but told a BBC reporter, incidentally. Actually, it was about compensation for Avey's forced labor in the POW camp.

However, since the BBC reported on Avey in November 2009, "the man who broke into Auschwitz" is a celebrity in England. He gave interviews to newspapers and TV stations, Gordon Brown, then British Prime Minister, handed him a medal for British heroes of the Holocaust, and currently Avey is working on his autobiography in his home in the northern English village of Bradwell, which will appear in ten countries - in May Also in Germany. That's why he is not allowed to interview right now, his wife Audrey explains on the phone.

Avey was confronted with the horrors of Auschwitz because he had been captured as a British soldier in North Africa by the Germans and taken to the POW camp E715, which was located on the Auschwitz camp complex. Every day he saw the cattle cars in which the Jewish prisoners were taken to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, he smelled the smoke of the crematoria and the burnt flesh; He saw the SS people abusing concentration camp inmates and relegating newly arrived Jewish forced laborers from Hungary to their bones within a few months.

The Auschwitz camp complex consisted of the Auschwitz I main camp, where at least 70,000 people were murdered, Auschwitz II, the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where at least one million people died, and Auschwitz III, the Buna / Monowitz concentration camp, where Denis was Avey came in. There were no gas chambers, no crematoria and no mass shootings. It was a labor camp in which the inmates were tortured to death by malnutrition, poor hygiene and hard labor. More than 25,000 mostly Jewish prisoners died as a result.

The writers Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel, later Nobel Peace Prize laureates, are among those who survived it. The Buna / Monowitz concentration camp was founded because the chemical company IG Farben wanted to build a huge factory there, in which among other things the synthetic rubber Buna should be produced. The group's own concentration camp is now considered a prime example of how deeply involved the German industry was in the Holocaust: prisoners who were too exhausted to continue their work were selected and sent to gas in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp seven kilometers away.

The prisoner of war camp E715, in which Denis Avey was interned from autumn 1943 to January 1945, was located next to the Buna construction site and not far from the Buna / Monowitz concentration camp. The Wehrmacht had set up the camp because the interned British prisoners of war should work side by side with Polish civilians and concentration camp inmates on the construction site. The number of prisoners in E715 fluctuated in the period of its existence between 600 and 1400. In mid-1944, E715 changed the location and moved so close to the Buna / Monowitz concentration camp that the prisoners of war from then on could not help but witness what next door happened: They saw through the fence, how concentration camp inmates were maltreated, and were woken by shots and screams at night.

Compared with this, their own existence was bearable. Because of the aid packages of the Red Cross, which they held as prisoners of war, they were not dependent on the miserable camp fare, they were allowed to have cigarettes, which they could trade for eggs, bread or clothing on the black market and if they did not have to work on the Buna site, they would play football and theater, read books from the camp library, or hear about the war via illegal radios. In the National Socialist racial ideology, the British were considered Aryans, which is also why the SS treated them more respectfully on the Buna construction site than the concentration camp inmates.

But those who put up with guards put his life on the line: it is known that inmates could be shot if they disobeyed an order. Avey also clashed with an SS man who punched a young Jewish prisoner in the face. "I do not know what came over me, but I insulted him and called him a subhuman," Avey says in a speech he delivered in January 2010 to the Holocaust Center, a memorial in Nottinghamshire. The SS man struck Avey in the face with his gun, injuring Avey's right eye so hard that it had to be removed after the war.

Although the prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates were forbidden to talk while working, the SS could not really prevent them from making contact. Many British encouraged the concentration camp inmates, gave them cigarettes or food, or left the already almost inedible soup they received at the construction site at noon, the "Stripeys," as the British called the concentration camp inmates for their striped uniforms.

Avey also did not abide by the contact ban and spoke with the concentration camp inmates about the beatings of the SS people, about forced labor and even about the gas chambers. Avey was surprised at how distantly they talked about death in the camp and about the monstrous, the unimaginable that happened only a few kilometers further in Auschwitz-Birkenau. In his speech to the Holocaust Center, Avey says, "Sometimes I asked, 'Where's Max or Franz?' And they said, 'Oh, he went through the chimney last night.'.jpeg)