When asked to draw a typical Dutch horizon, aspiring local artists naturally draw a flat line. When I was asked however, I simply drew a blank.

My knowledge of local art, like that of the vast majority of the Dutch, is limited to a few well-known facts. Jan Steen produced funny paintings of the working class in pub and street settings, Vermeer loved his yellows, Rembrandt loved light on a dark background and Van Gogh produced art full of colour and life.

As with many geniuses, their talents are often counter-balanced; in Vincent’s case, he went slightly mad. Cutting off the lower part of his left ear, he gave it to a prostitute named Rachel, asking her to “keep it carefully.” Many theories attempt to explain this, but the one that perhaps comes closest involves the bullfights at Arles; after slaying the bull and displaying its ear to the crowd, the victorious matador would then present it to a lady of his choice.

As with many geniuses, their talents are often counter-balanced; in Vincent’s case, he went slightly mad. Cutting off the lower part of his left ear, he gave it to a prostitute named Rachel, asking her to “keep it carefully.” Many theories attempt to explain this, but the one that perhaps comes closest involves the bullfights at Arles; after slaying the bull and displaying its ear to the crowd, the victorious matador would then present it to a lady of his choice.

We know what he looked like after his bloody act, because he painted a self-portrait showing a bandaged ear. This portrait however is not entirely accurate, because it shows a bandaged right ear, whereas in real life it was his left ear that he cut off. Clearly, Vincent sat in front of a mirror as he applied the brushstrokes that reveal a rather sombre looking man.

What drove Vincent mad? Some say he was upset, because his brother, who helped him financially, had just announced his engagement. Vincent, a relatively poor man who only ever sold a single painting in his life, was faced with the terrifying thought that his source of funds was about to become as dry as the Kalahari.

The famous Dutchman took French impressionism, added a lot more life and produced post-impressionism for the benefit of the world. I love his paintings. I thought Renoir’s Luncheon of the boating party was my favourite, but now I’ve discovered van Gogh’s The ploughed field, with its rich shades of brown soil.

Not all the masters were famous. Some were decidedly infamous, like the clever artist who rose to fame briefly at the end of the Second World War. Around this time, the allies stumbled upon a salt mine in Austria filled with art treasures plundered by the Nazis. To ensure the pieces were handled properly and traced back to their owners, the military hired an art expert.

Among Göring’s collection was a painting by the famous Dutch artist Jan Vermeer. No one had heard of it, but its former owner was discovered to be a nightclub operator in the city of Amsterdam. His name was Han van Meegeren.

Han was arrested in 1947, and charged with selling Dutch art treasures to the Germans. However, he swore blind that the paintings he sold were his own creations – in other words, they were all forgeries. Was Han lying, because the charge of treason for collaboration carried the death sentence in the Netherlands? Clearly, just claiming his innocence was insufficient. Han had to prove it, or he could swing at the end of a rope!

He was given the chance.

Born Henricus (Han) Antonius van Meegeren in the city of Deventer in 1889, Han  quickly developed a love of art to the disgust of his father. As he grew older, he developed a strong interest in the Dutch classical painters, and tried to emulate their style. Because his work was based on a 1600s style, it seemed outdated in the period of Matisse and Picasso, so Han did not receive the recognition he felt he deserved.

quickly developed a love of art to the disgust of his father. As he grew older, he developed a strong interest in the Dutch classical painters, and tried to emulate their style. Because his work was based on a 1600s style, it seemed outdated in the period of Matisse and Picasso, so Han did not receive the recognition he felt he deserved.

Frustrated, Han van Meegeren pledged to make fools of all the so-called experts. He had the perfect accomplice in Jan Vermeer, the 17th Century Dutch master whose work became popular only in the 1900s, and of whose paintings only 35 or so were known to exist. No preliminary drawings, sketches or early work existed, so nobody would be surprised if a few were to suddenly pop up with a reasonable explanation.

Intimately familiar with the style of Vermeer, Han made the decision to create a new “Vermeer” and sell it to a particular critic he despised, a flamboyant museum director and expert on the 17th Century Dutch masters. His name was Dr. Abraham Bredius. Because this art critic loved the limelight, Han hoped he would gobble the forgery hook, line and sinker and so make a fool of himself.

How did Han van Meegeren produce his forgeries? Over a period of 5 years, he had developed techniques to ensure they would be accepted. After buying a 17th Century painting, Han would remove the paint to be able to re-use the canvas. Using 17th Century techniques, he would then make his own paints; not the standard oil paints which took too long to dry, but Bakelite-based ones. Remember Bakelite? The old black phones were made of it.

Phenol and formaldehyde were used to harden these paints and give them an old look. After completion, the painting was baked dry before being rolled over a drum to induce cracking, and then washed in black ink to fill the cracks.

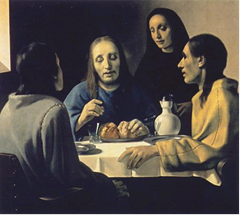

The day arrived when Han finally got his chance to dupe the expert. At his studio in the south of France, he allowed Dr. Bredius to “discover” his forgery entitled The Disciples at Emmaus.  The pre-eminent art expert was taken in completely. He and the art establishment believed Han’s story that a family fleeing Nazi persecution had left the “Vermeer” behind for Han to sell.

The pre-eminent art expert was taken in completely. He and the art establishment believed Han’s story that a family fleeing Nazi persecution had left the “Vermeer” behind for Han to sell.

At last, the Dutchman received the recognition he felt he deserved, which entitled him to walk in the footsteps of the masters. Being offered 1.8 million guilders for the painting convinced Han to accept the money instead of revealing that he was about to be paid for a forgery. He would later claim that he was never in it for the money, which I swear is inherently impossible for a Dutchman. One must assume a huge chunk of cheese fell off his cracker as he uttered those words.

His conscience apparently clear, van Meegeren went on to produce several more paintings between 1938 and 1945, becoming a multi-millionaire in the process. One of the paintings was entitled Christ With The Adulteress, the very “Vermeer” discovered in the salt mine. Göring had purchased it, though probably with counterfeit money that the Germans excelled at making.

To prove his innocence at the trial, van Meegeren painted another “Vermeer,” which he entitled Christ and the Scribes in the Temple. To help make his case airtight, he told the investigating panel exactly what x-rays would reveal underneath his forgeries.

The smiling judge changed the charge of treason to forgery.

The Dutch loved the story of the man who had duped the art establishment and Nazis, so Han became hugely popular, second only to the Prime Minister. This scoundrel had achieved what he had sought all along – he had made a fool of the local art experts, and in doing so earned a fortune estimated at $30 million. He lived like a king in a period when even the great Mondriaan was renting a small house in Paris.

On 29 December 1947, those in the Dutch art establishment probably breathed a huge sigh of relief. On that day, their nemesis, considered one of the most ingenious art forgers of the 20th Century - passed away.

Artist works are only Famous and sell-able after the artist death to line the pockets of museums and art "EXPERTS".As artist, we NEVER paint or draw to sell.Only to shine light into the darkness and expose the evil which lies within or the beauty of ,and or darkness in the portraits which inspire the artist hunger for exposure.