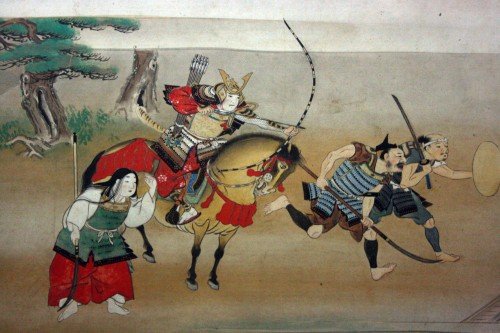

The proud warrior class of the samurai (meaning 'those who serve‘) grew from bands of mercenaries hired by feudal landowners in the 11th century to win them control ol Honshu, Japan’s main island. These mercenaries lived by the cult of the sword. worshipping athletic prowess and martial skills. They had deveIoped a fierce loyalty to their masters and a fearlessness that made them formidable adversaries. They fought in elaborate armour, wielding their most prized possession, double-edged sabre with which they could cut a man in half.

Later the spartan principles of Zen

Buddhism, with its love of nature, softened their fighting zeal. It became fashionable for them to live sparse and frugal lives during the Kamakura era (1192-1333), when the ruling warrior family Minamato moved their seat of power to the eastern city of Kamakura. Confucian thought, with its emphasis on honesty, also influenced the samurai.

By the 16th century these principles ' had become codified into bushido (meaning ‘the way of the warrior')‘. First loyalty remained to the samurai lord and to skill with the sword, but the warriors also became an Oriental version of the Christian knights, embracing duty, honour and nobility of spirit.

In 1871 the last 400,000 samurai were pensioned off and became shizaku, Japanese gentry. Most were absorbed into the civil service and business management. Five years later it became illegal for anyone but the military to wear a sword. The virtues of the samurai were, however, kept as an ideal for the whole nation to follow, with the emperor as the supreme object of loyalty. This was the key that in times of crisis turned Japanese nationalism into a potent force.