WWII: Canada and the Fight for the Atlantic

The Second World War saw the Allied forces quickly put into a state of desperation as the Nazi war machine swept across continental Europe. Only the British Isles remained, sieged within their island. Their life line was the convoy of cargo ships that crossed the Atlantic from North America. Canada, the next largest Ally at that time, was to provide the defence for the shipping convoys.

A monumental undertaking, The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) was tasked with defending these convoys to and from Europe, as well as defending the Canadian coastal shipping lanes. Historically, the ‘Battle of the Atlantic’ is often considered a defeat for the RCN as the St. Lawrence Seaway was closed to traffic and the RCN was for a time relieved of convoy escort duties in the Mid-Atlantic. In the context of the baffling task given to the RCN, its achievements are often dismissed and should be recognized.

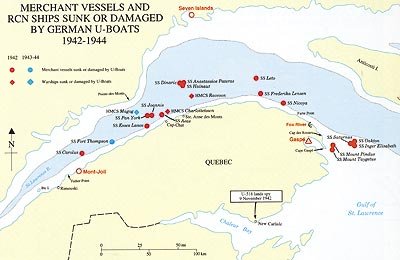

The St. Lawrence Seaway allowed newly built ships and merchant vessels to supply in the inland cities and then gather in convoys in Halifax, Nova Scotia and St. John’s, Newfoundland before departing for Britain. It was a key passage way for the war effort. As U-boats made their way into the Gulf and up-river, convoy and military losses began to mount in the early 1940’s. The RCN reacted with the resources it had placing more ships in the area. They also cooperated with the air force, establishing constant air surveillance. A credit to their efforts the RCN had made a network to spot the German vessels and defend the immense seaway. In the late summer of 1942, a group of German U-boats made daring assaults on the Seaway resulting in heavy losses. This helped finalize the decision to close the Seaway on 9 September, 1942.

After the release of war documents we now know many of the losses were due to the boldness and luck of just a few U-boats, namely German vessel U-517. German documents indicate that they had been pinned down and unable to effectively fight against the growingly sound RCN combined air-sea defensive system. In an address to the House of Commons about the closure, Angus L. Macdonald, the Minister of Defence for Naval Services stated, “...I can say that if you only lose three tons out of every thousand which you have at sea you are doing pretty well"." This is only 0.3 percent of your shipping. The reason to close the Gulf was a strategic move, rather than a failure. The German U-Boats were forced to move to easier waters.

The most compelling argument of failure is the removal of Canadian sailors and ships from the Mid-Ocean Escort Force (MOEF) in January of 1943. This was evidence that the RCN was unable to do the task, but if you exam the circumstance of the RCN, their endurance can be appreciated. At first, the RCN had no intention of open ocean escort protection, but the British Royal Navy (RN) in May of 1941, asked the Canadians to take this task so British fleets could remain in closer defensive positions at home. This was an overwhelming task for the RCN.

The German Navy (GN) in 1939 did not yet have a substantial U-boat fleet and the RCN was able to cross convoys with relative ease. As Hitler and the German Command realized the importance of stopping these convoys production of U-boats increased and so did the attacks on the convoys. Cracks began to appear in the RCN as merchant and military vessels were lost due to lack of escorts, training and experience. Despite these losses, convoys still made it across to maintain British resistance.

In the fall of 1942, the St. Lawrence had been deemed too dangerous by the GN and the United States (US) had fortified convoys on their East Coast. The U-boats were therefore redeployed in the North Atlantic in an area called the ‘Black Pit’. Here it was the Canadian escorts which bore the brunt of this change. With the RCN escorts facing skilled and large U-Boat Packs, losses pilled. The US war machine was now fully underway and its massive industrial effort was delivery dozens of escort ready ships, to which Canadian shipbuilding could not yet compete. The RCN was then relieved. It was while the RCN was upgraded and properly trained that the GN was handed some of their worst defeats from the US Navy (changing the momentum of the battle). With the RCN was sidelined, this only deepened the opinion of failure.

When the RCN returned to the theatre they were trained, existing ships had been reequipped and the shipbuilding yards in Canada had produced its first frigates. The British and American commanders had recognized the Canadian effort and gave them full operational command of the North Atlantic convoys. The RCN returned to its duties and it could now effectively defend the convoys and go on the offensive. Under its self-command the RCN organized its own support groups for submarine hunting. In the first year they took command Canadian ships sunk or assisted in the sinking of eight U-boats.

Before the War, the Navy consisted of just six destroyers, a few minesweepers and coastal vessels. The thought of having to defend against U-Boats or spear head the Atlantic crossing was very distant. The corvettes were designed to protect Canadian waters with trained and equipped crews. When the RCN was tasked with MOEF in 1941, the RCN was forced into immediate action. Undertrained crews and small corvettes ships battled rough seas and U-boats to the point of exhaustion. As the Americans remained neutral the RCN was forced to spread its fleet along the eastern US shore. Later when the African Campaign climaxed in Operation Torch (the joint American-British landing in Africa) six more corvettes were taken from the RCN fleet to assist in the landing.

Despite all the tasks it was given outside the North Atlantic theatre, in the years it participated in MOEF, it was still successful in bringing convoys to Britain. Lieutenant P. Evans perhaps put the RCN’s efforts best, “...remember the Canadian corvettes – those far flung, storm tossed little ships on which the German Fuhrer had never looked and yet which have, since 1940, stood between him and the conquest of the world." The Royal Canadian Navy had maintained the British supply line in the North Atlantic.

Soures: 1. Copp,Terry. Achievement on the Atlantic. From Nation at War: Essays from Legion Magazine. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication, 1996.

2. Milner, Marc. North Atlantic Run. Canada: The University of Toronto Press, 1985.

3. Sarty, Roger. The Battle of the Atlantic: The Royal Canadian Navy’s Greatest Campaign 1939-1945. Ottawa: Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data, 2001.

4. Sarty, Roger. The “Battle We Lost at Home” Revisited Official Military Histories and the Battle of the St. Lawrence. In Canadian Military History, Volume 12, Numbers 1&2, Winter/Spring 2003.

5. War at Sea: The Black Pit. Dir. Brian McKenna. Perf. Terence McKenna, Carl Marotte and Mathew Mackay. VHS, 1995.

6. Ships and Harbour Photos, 2007, http://www.shipsandharbours.com/picture/number2065.asp, (18/10/11).

good to know

Congratulations @elendilyemm! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP