( )![farmer-suicide-india-story.jpg]

)![farmer-suicide-india-story.jpg]

The swiftness with which the protests spread to other parts is indicative of farmers’ frustration with their governments’ unkept promises and superficial measures to end their hardship, as well as the declining economic viability of agriculture.

The farmer unrest in Madhya Pradesh (India) took a drastic turn last Tuesday with the death of five farmers in a police firing. Angered by the incident, protestors intensified their agitation against the government, notwithstanding the chief minister’s efforts to do damage control. Farmers in MP had been protesting since the first week of June demanding Minimum Support Prices (MSP), as well as a complete debt waiver.

Maharashtra had simultaneously witnessed similar protests, with farmers refusing to sell their produce at Agricultural Market Produce Committee (APMC) mandis till their demands of higher MSP and loan waivers were met. Farmers here had asked the central government to deliver on its promise of adjusting MSP to be cost of production plus 50 percent profit – a price that was declared impractical by the Centre in 2015.

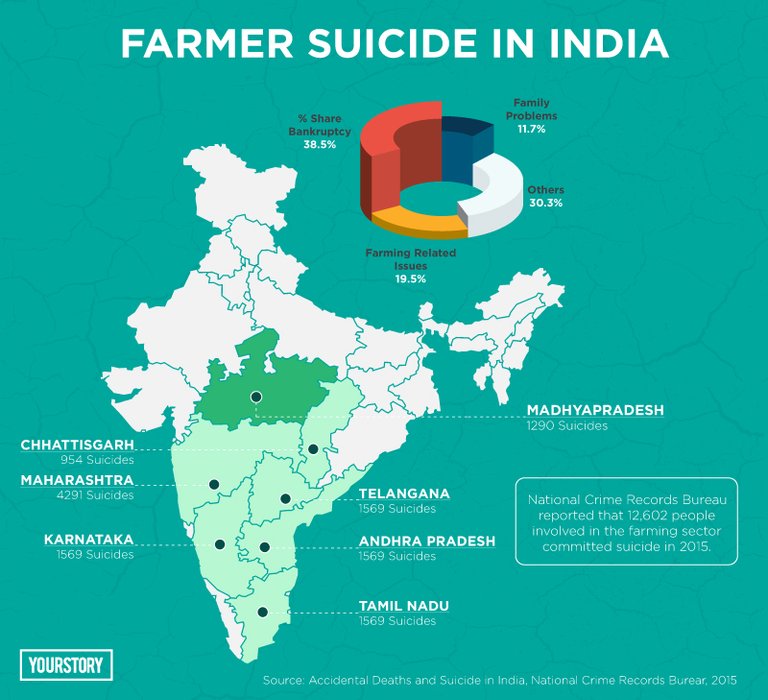

After two years of drought resulting in successive crop failures – a circumstance that could have been avoided had the irrigations facilities for which tens of thousands of crore rupees is invested, actually materialized – farmers were finally relieved to receive abundant rainfall and a good harvest. Yet, they are still struggling to make a profit on their produce, and farmer suicides continue unabated.

That’s because the present situation isn’t born out of a paucity of agricultural output but in fact, an excess of produce. Overproduction of food can push farmers into distress just as much as a failed harvest. A supply glut, such as the one presently faced by pulses, chili, potato, and onion cultivators in India, generally leads to a price crash, resulting in poor returns. But it is exactly for situations such as these that the MSP policy is in place in the country – to shield farmers from market volatility. However, the states have either failed to procure most of the produce at MSP or are really slow in the process, forcing many farmers to sell far below the set price.

The immediate causes of these agitations, ironically, are of the ruling party’s own making, beginning with the aforementioned U-turn on their electoral pledge to considerably raise MSPs. Followed by it came Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath’s announcement of a Rs. 36, 359 crore loan waiver for farmers in his state, which provoked farm communities in other states to demand the same.

Moreover, demonetization continues to affect farmers and the rural community as a whole, which is still experiencing a cash shortage. As the sowing season of Kharif crops approaches, they are scrambling to find the capital to buy inputs. Coming at a time like this, the price crash only aggravates their distress.

( )

)

And interestingly, the excess production of tur daal that led to the commodity’s price drop was, as it happens, a combination of the centre’s pulses promotion programme, its foreign import deals, and farmers’ dependence on last year’s prices. After a shortfall in domestic production and a subsequent price rise, the Center raised the MSP of pulses and included an additional bonus for the 2016-17 Kharif crop as an incentive for its cultivation. Farmers were also motivated by the high market prices of 2015-16, and hence expanded the area under pulses cultivation.

The ministry of agriculture and farmers’ welfare estimated domestic pulses production for the year 2016-17 to be 22.14 million tonnes, well above the 20.75 million tonnes target fixed by the government. However, the Center set itself a procurement limit of only two million tonnes for pulses. According to the Hindu Business Line, as of February, it had obtained a total of 1.02 million tonnes, but this was inclusive of 0.4 million imported tonnes meaning, the government purchased a paltry 0.62 million tonnes from our farmers.

Despite being aware of a surplus production, the Centre continued to import pulses from other countries as it is bound by import contracts, such as the one it signed with Mozambique just last year. Therefore, by the end of March, more than 4 million tonnes of imported pulses had entered the Indian market, increasing competition for local farmers.

If the MP and Maharashtra governments manage to control the agitations and meet their farmers’ demands, all that will do is calm them down for the moment. But it won’t help much in the way of tackling the real crisis, which runs deep into the policies that dictate the working of our agricultural sector – policies that have created an environment susceptible to such crises.

Higher MSPs and widespread procurement of only certain commodities by the government, a practice that has been in place for decades now, distorts cropping patterns leading to surplus production of a very specific set of crops, as farmers are encouraged by the promise of good returns. And it doesn’t help that there is no system of information dissemination and coordination to notify farmers of cropping patterns within and outside the state, and the scale on which their chosen crop is simultaneously being grown across the country. Therefore, they have no way of anticipating overproduction or protecting themselves by cultivating a backup crop.

Additionally, due to the lack of a sufficient number of cold storage facilities in the country, farmers do not have the option of waiting out a price collapse and selling when it stabilizes. Nor can the government stock the excess produce and speed up procurement. Farmers either have to make distress sales or leave their harvest to rot. Based on latest estimates, India has a cold storage capacity of 31.8 million metric tonnes in 6,891 facilities. However, more than 60 percent of them are spread across just five states – Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Punjab.

Furthermore, even if there wasn’t a supply glut, and the government was able to purchase produce at the assured price, let’s not forget the friendly neighborhood middlemen who distort prices and cheat farmers out of their actual returns. Raising MSPs and allowing farmers to directly sell in open markets is pointless as long as the supply chain is riddled with exploitative intermediaries.

The agricultural sector is in dire need of structural and policy reform. Instead of encouraging unsustainable farming practices through subsidies to agricultural corporations, constricting crop diversification with selective MSPs, and resorting to temporary fixes like loan waivers, the government needs to rethink credit, market, and land policies as well as emphasise on investment – investment in irrigation infrastructure, in sustainable farming methods, in research and extension, in market information systems, and in storage, packaging, and transportation facilities.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi revealed his ambitious goal of doubling farm incomes by 2022 in 2016, and his seven-point action plan addresses several of these issues. However, what matters here is commitment, especially considering the magnitude of the task and the time limit within which to achieve it. Nevertheless, even if the government does not meet its target, the execution of its action plan alone will still be a step forward for the sector.

The swiftness with which the protests spread to other parts is indicative of farmers’ frustration with their governments’ unkept promises and superficial measures to end their hardship, as well as the declining economic viability of agriculture. Perhaps this display of solidarity between them might just become the start of a long-awaited farmers’ movement to end the agricultural community’s crisis.

Great article!

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://yourstory.com/2017/06/mp-farmer-protests-lessons/

Thanks for the good article

Congratulations @rohit8055! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!