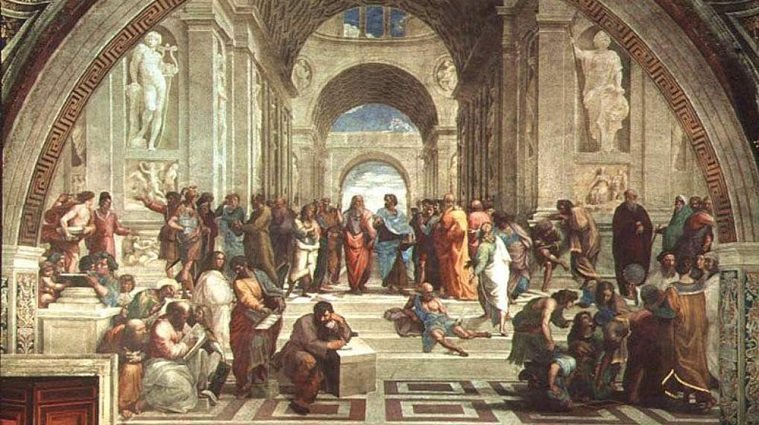

The variability of sensory knowledge according to Plato is due not only to the variability and transience of the perceived sensual material objects. In addition to the sensual being, according to Plato, there is also a superstitious, super-spiritual spiritual world that can not be perceived sensibly, but to which one can reach and think - it is the mind. Knowledge of this world is a true, mutual knowledge, Plato called "epistimi", understanding, knowledge. We have the first kind of knowledge of reason, as in geometry, algebra, or logic. The second type is an immediate, complete, common understanding of something. It is equal to what we now call intuition, immediate inner conviction, contemplation, and rational faith. According to Plato, this is the highest real knowledge because it is knowledge of the true, eternal, invariable, spiritual being.

As we have seen, according to Plato, there are two types of reality-one changeable, sensible, transient, untrue, and an immutable, non-intuitive, intransigent, real, spiritual one. One sense we perceive, the other thinks. For one we have specific notions, for the other we have common unchanging concepts. One is composed of specific individual things, the other is composed of ideas. The doctrine of ideas is central to Plato. He also introduces the very word "idea" into philosophy. However, we should not mix it with today's meaning of the word "idea". Today, under "idea," we most often understand, have a certain concept or idea of something to know about it. For example, we say that we have an idea of a feudal order, an idea of a triangle, a mountain idea, and so on. By "idea" we still understand a certain plan: someone is rich with ideas-with initiatives and rest.

For Plato, however, the idea is something else: it is not just a mental image of this or that person, but a reality whose corresponding mental image is the notion. At the same time, ideas are not only real but only real and real. It is assumed that what is given can not be but the individual things. This is given to us: mountains, rivers, trees, stones, and then ideas come for one thing or another, as they are something secondary, arbitrary, determined by the realities. According to Plato, it is exactly the opposite: first, ideas exist as eternal essences, and then there are the concrete incarnations and insights of these ideas. First there is the "horse" and it makes possible and actually existing, like horses, the individual specimens of this equine animal. First there is "potato" and only thanks to it has specific potatoes. First, there is "blossom", and then as its specific manifestations and incarnations, realizations for the individual roses.

Moreover, these separate roses grow and diminish, bloom and blossom, and the "bloom" remains unchanging, independent of either the number, the time or place, or even the type and condition of particular roses. They do not determine it, but on the contrary, it only determines them: without "bliss" in themselves they would not be roses. Only their belonging to it, their accomplices to it, the wearing of it makes them roses. The same is true of horses and horse, potato and potato, beautiful objects and beauty of men and humanity, and so on.

Thanks for that clear explanation. Do you know how Plato explains how the ideas can materialize ? It's something I never realy understood... Everytime I think about Plato's Ideas, I really can't figure how the Idea of rose can produce the roses. It seems to me that, no matter how revelant is this philosophy, there could neve be a "connexion" between Ideas and the material world...

I think they can't be materialized. It is the same for me as the idea of Nietzsche about super-human, when the nacist try to materialized it, they only vulgarize the idea.

When you write about Plato's "Idea," is that the same thing as the ideal form, or am I missing something? I'm going to confess my knowledge of ancient philosophy is very spotty.

Yes, it involves it in his meaning. :)

Di indonesia banyak keberagaman suku, anda pasti penasaran bukan,.. ayo telusuri 😊