Part 1 can be read here.

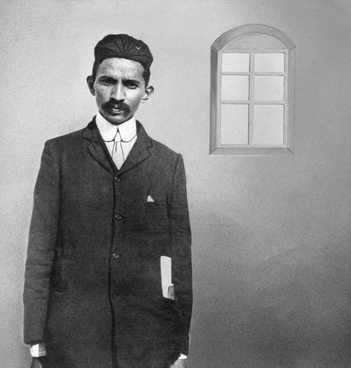

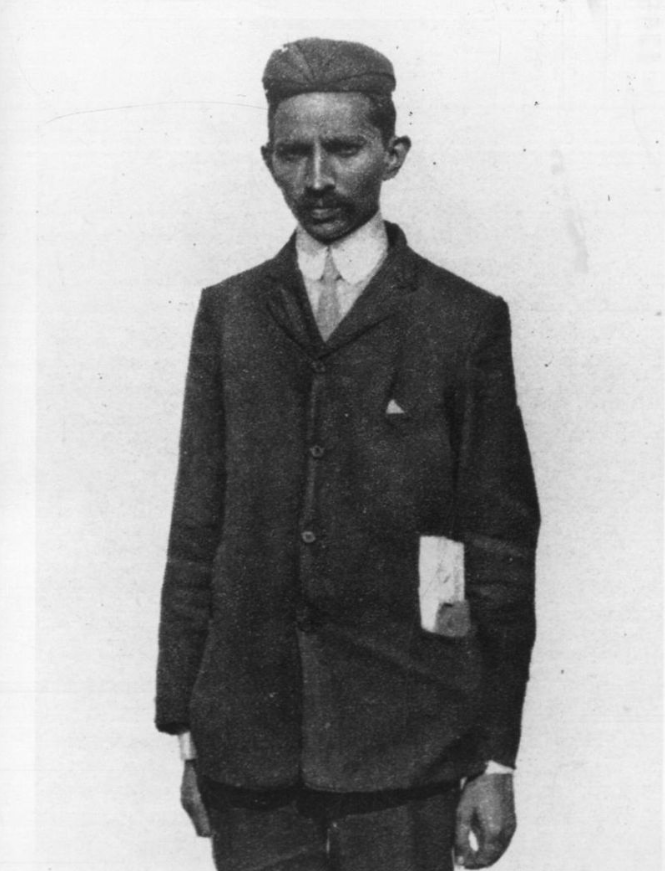

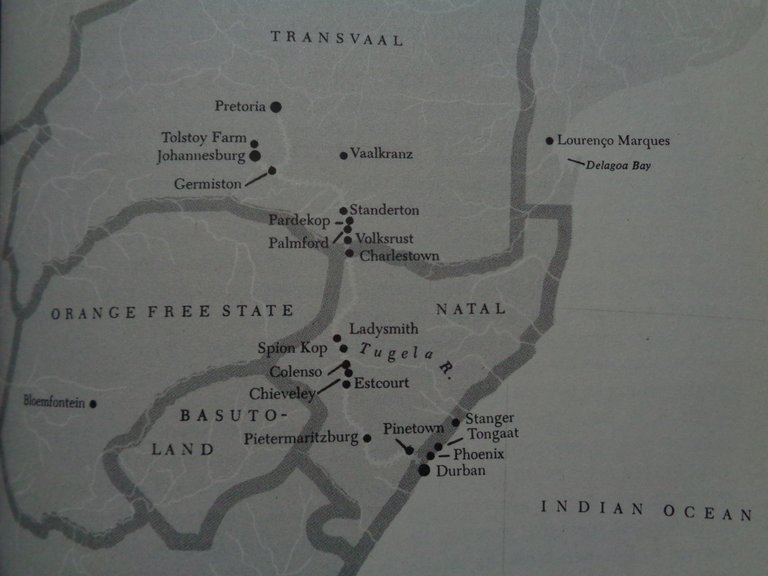

On Friday, June 2, 1893, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi woke up aboard a northbound train in a first-class compartment. After a little more than a week in South Africa, the 23-year-old barrister was halfway through his 500-mile journey to Pretoria, capital of the Boer-controlled province of Transvaal, where he expected to work for the next year representing his client's interests in a lawsuit. Gandhi was anxious to arrive at the next station. He was a day behind schedule, having been thrown off an earlier train for refusing to vacate his first-class berth when a white passenger objected. The resulting night, spent shivering in the waiting room of Pietermaritzburg's railway station, had forged a determination to root out prejudice, even if it meant suffering hardships.

Gandhi's train steamed into Charlestown, which lay on the border between the British-controlled province of Natal and the Transvaal. The rail line ended there, so the next leg of his journey would be by stagecoach. Leaving the British territory brought a greater opportunity for hardship. In his biography Gandhi Before India, Ramachandra Guha describes the two provinces:

[T]he Transvaal was ruled by the Boers. They were a farming people, devout and dogmatic, convinced that those who were not white and Christian had no claims to citizenship in their land. The British in Natal were more interested in trade and commerce, and less interested in the Book. But they were not without prejudices of their own.

The “leader” of the stagecoach was a large Dutchman, and he was not enamored with the idea of the “coolie barrister” riding with the other passengers. First, Gandhi was told – falsely – that his ticket had been canceled. Then, the Dutchman climbed into the coach with the other passengers, directing Gandhi to take a seat on the coachbox next to the driver. Forcing his way into the coach wasn’t plausible, so he accepted the insult and climbed up to take the Dutchman’s usual seat.

As he rode, Gandhi must have considered his options. Could he slip inside the coach at one of the stops and displace the Dutchman? Protest to the company when they stopped for the night at Standerton? Say nothing and just accept the hardship? That afternoon, the warm sun forced the issue. At one of the stops, the Dutchman, desiring the fresh air of his regular seat, spread out a dirty rag on the footboard and directed Gandhi to move down there.

Trembling, Gandhi refused. “Now that you want to sit outside and smoke, you would have me sit at your feet. I will not do so, but I am prepared to sit inside.” He had hardly finished the sentences when the attack came. Cursing and boxing Gandhi's ears, the Dutchman tried to rip him violently down from the stagecoach. Gandhi grabbed the brass rails of the coachbox and hung on, declining to fight back. Was this the principled nonviolence he would later advocate or cowardice? Gandhi hints at an answer in his autobiography: “He was strong and I was weak.”

Whatever Gandhi's motivation, his passivity brought a resolution. “Stop, leave him alone,” the other passengers cried. The beating stopped first, then the profanity tapered off. Determined to save face, the Dutchman claimed the third seat on the coachbox, displacing the African servant who had been sitting there and forcing him to perch on the footboard. Once settled, the stagecoach resumed the trip. Biographer Jad Adams observes that Gandhi learned a valuable lesson – public injustice can draw protests from those otherwise disinterested.

As the coach rattled along, we can picture the stocky Dutchman talking jocularly with the driver, as though Gandhi wasn’t a few feet away, describing what a beating he would give the “coolie barrister” when they stopped for the night. Gandhi had no choice but to sit stoically as the hours passed, but his heart and thoughts raced. He considered the very real possibility that he would never reach his destination alive. Fortunately, when the stagecoach pulled into the village of Standerton, a group of Indians was there to greet him. His employer, Dada Abdulla, had sent word ahead, and Gandhi was escorted safely away.

Before he would rest for the night, Gandhi wrote out a letter to the stagecoach company’s local agent. Drawing on his experience preparing court briefs, Gandhi described the insults, assault, and standing threat he had received as a passenger with a valid ticket. He requested an assurance that he would be able to continue his journey peacefully. Much to his relief, the prompt reply informed him the Dutchman would not be present when the trip continued, and a seat inside the morning coach with the other passengers was promised to him.

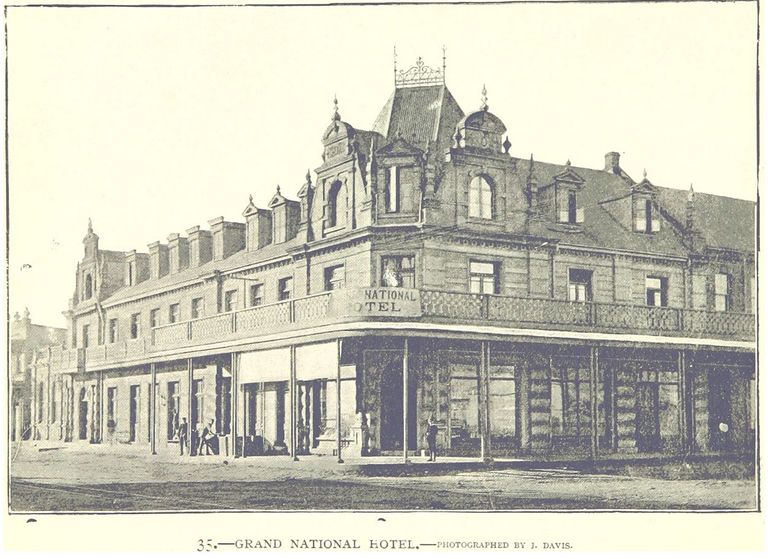

Saturday’s ride was long but uneventful. It was dark when they arrived in the city of Johannesburg, and Gandhi disembarked, expecting someone to greet and guide him. No one did. His autobiography passes this off as a missed connection and gives the benefit of the doubt to the man who was supposed to meet him, but it seems unlikely there was a dearth of Indian passengers arriving by stagecoach. Rather than wait at the station, Gandhi took a cab to the Grand National Hotel.

The Grand National Hotel was one of the largest hotels in the city, taking up much of a city block and boasting of more than 120 bedrooms. A few years later, Mark Twain would be a guest there when he visited Johannesburg. Mohandas Gandhi walked in, perhaps admiring the high ceilings and imported balustrades, and asked for a room. The manager scrutinized the young man for a moment, the juxtaposition between his smart English dress and dark skin, then politely informed him no room was available. Gandhi retreated back to the cab.

At the offices of his local contact, Gandhi found Sheth Abdul Gani waiting for him. He related the story of the Grand National Hotel and was rewarded with laughter. “How did you ever expect to be admitted to a hotel?” The Sheth went on to explain that life in South Africa wasn’t for the likes of Gandhi; insults were to be expected and ignored. He grew more serious; the final leg of Gandhi’s journey would be by train, and he would have to travel third class. Indians were never issued first- or second-class tickets in the Transvaal. Gandhi bristled at the idea that it would be impossible.

Perhaps that night he recalled his confrontation with his Modh Bania caste elders five years earlier, when they forbade him from studying in London. The elders had claimed it was impossible to do so without violating their religion. Gandhi had already made a vow to his mother that he would abstain from alcohol, women, and meat while abroad, and despite being declared an outcaste for disobeying the elders, went anyway and kept his vow. He had accomplished what he had been told was impossible... could he do such a thing again?

By morning, Gandhi had worked out a strategy. First, he sent a letter to the station master, explaining that he was a barrister who needed to reach Pretoria quickly, and that he always traveled first class. Second, he requested no written reply, ostensibly because of the urgency, but tactically to defer any decision until he could make his case in person. Gandhi arrived at the station neatly dressed in a frock-coat and necktie, and he addressed the station master in faultless English. Third, he placed a gold sovereign on the counter to pay for his fare.

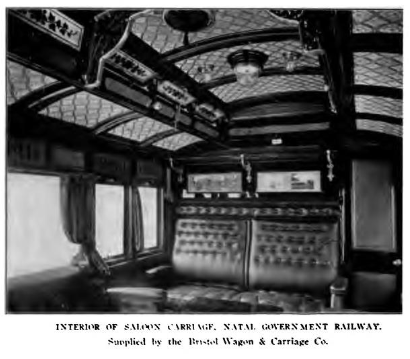

The station master accepted the gold and issued Gandhi a first-class ticket, proclaiming that Gandhi had his sympathies. However, there was one condition. If there was any trouble from the guard on the train, Gandhi must leave the railroad company out of it. After agreeing, Gandhi displayed his prize to Abdul Gani, who, while impressed, offered a further caution. He predicted the guard and passengers would not let Gandhi ride in peace.

This nearly came true. A few miles down the line, the guard discovered Gandhi in first class and ordered him back to third. Once again, however, a public injustice aroused sympathy from a bystander. The Englishman sharing the compartment berated the guard for his racist demand, and insisted Gandhi make himself comfortable. He did so, and around 8:00 p.m., they arrived in Pretoria.

Once again, there was no one there to greet him. Gandhi had practically resigned himself to spending another night at the station when a visiting African-American offered to show him a small hotel where he might be able to stay. Although skeptical, Gandhi put aside his doubts and agreed to follow the man.

Johnston’s Family Hotel was a much simpler establishment than the Grand National Hotel. His guide spoke privately to Mr. Johnston, another American, who conditionally offered Gandhi a room. While the owner claimed to be personally free of color prejudice, he feared Gandhi's presence might cost him customers. Gandhi could stay the night, if he agreed to have his dinner in his room. He accepted.

In his room, Gandhi waited for the waiter to bring his dinner. Perhaps he reflected on what a long, strange trip his journey had been. There had been hardships; unrepentant racists had pushed him around, even physically assaulted him based on the color of his skin. The hardships had tested him, but he had emerged stronger, and more importantly, victorious. He had completed his journey safely, even arriving in Pretoria in a first-class compartment, something that locals had told him was impossible. But that success would not have occurred without the support of both friends and strangers.

Sources:

Photos from Wikimedia Commons, The Engineering Magazine, Volume 14 (1903), and The Life and Death of Mahatma Gandhi (Payne, 1969)

Gandhi Before India (Guha, 2014)

An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth (Gandhi, 1927)

Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality Heritage Assessment Surveying Form (2002)

Part 3 can be read here: https://steemit.com/gandhi/@thegandhiguy/gandhi-in-south-africa-part-3