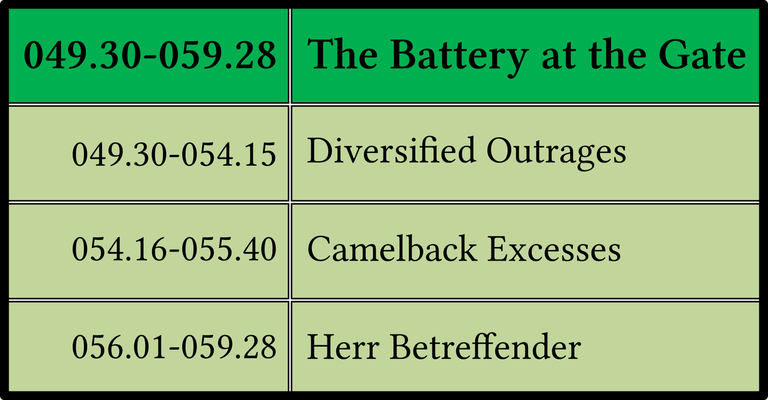

The last ten pages of Chapter 3 of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake comprise an episode known as The Battery at the Gate. This paragraph commences the second of the three subsections into which the Battery may be divided: Camelback Excesses (RFW 054.16–055.40). In the published book this section is less than two pages long and comprises a pair of paragraphs.

First-Draft Version

The earliest draft of the first of these paragraphs comprised only a handful of lines, recounting the fates of the two victims―ie Issy―of HCE’s Crime in the Park. Joyce originally planned to place this section immediately after the Plebiscite and Street Interview (RFW 047.13–049.29), which concluded with an episode involving two girls, Questa and Puella and three drummers:

First these outrages were thought to have been instigated by either or both of the rushy hollow heroines but one drank carbolic and her sister in love, finding she stripped well, felt her hat too small for her. But a little thought will allow the facts to fall in and take up their due places. If violence to life, limb and goods has as often as not been the expression, direct or through male agents, of offended womanhood has not levy of blackmail from the earliest ages followed upon in worldlywise? ―Hayman 74

One of the girls commits suicide by drinking carbolic acid―a not uncommon way of committing suicide in the 1920s―while the other gets a swelled head and blackmails HCE. Both details―the drinking of carbolic acid and the swelling of the head―were lifted by Joyce from stories in the 27 January 1923 issue of the Evening Standard.

By the time Joyce had finished revising this paragraph it had grown to more than a page in length and had become much more obscure. The sentence in the middle of the first draft―But a little thought ... due places―was dropped and replaced by twenty-eight lines of brand new material, drawn from the usual bewildering variety of sources. These revisionist additions recast the two girls as instigators of the attack on HCE rather than the victims of his crimes.

The first ten or eleven lines do little more than elaborate the opening sentence of the first draft.

velveteens gamekeepers, from the fact that they traditionally wore velveteen―a kind of cotton―trousers. I presume this alludes to the three soldiers―Shem, Shaun & the Oedipal Figure―who spy on HCE in the Park. The Plebiscite and Street Interview mentioned two velvetthighs and concluded with a reference to their three drummers.

dimities Dimity comes from the Ancient Greek: δίμιτος [dímitos], of double thread, so dimities may refer to the two Issys, or to the twins Shem & Shaun.

a fivefinger span a handsbreadth. FWEET defines a five-finger span as a cluster of keys on the piano, but I don’t see how this is relevant.

hence these camelback excesses HCE. This attack on HCE’s reputation is like the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Oh! Oh! In Germany 00 (Null-Null) is sometimes used to indicate a WC or public toilet. HCE’s Crime in the Park often involves him peeping at two young girls as they urinate amongst the foliage. Hence the references to the two girls as intoxicating liquors―margarita and posca―and to HCE as binocular man.

Dramatis Personae

Most of the additions to this paragraph were in place when a version of this chapter was published in Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul’s literary journal transition in June 1927. Several characters from legend, history and literature were given rôles to play in the expanded drama:

dilalah Delilah, the woman who loved and then betrayed Samson. By replacing de- with di- Joyce underscores her two-faced nature. A note in one of his Finnegans Wake notebooks equates her with Brangäne, Isolde’s handmaid.

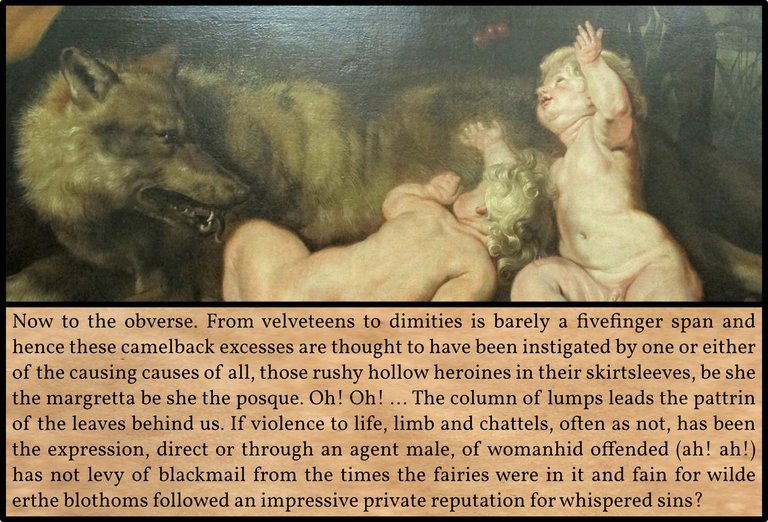

Lupita Lorette Spanish: Lupita, a diminutive of the female given name Guadalupe, which is derived from the toponym meaning Valley of the Wolf : the name, allegedly, of one of Saint Patrick’s sisters. French: lorette, prostitute, after the Parisian church of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. Latin: lupa, she-wolf : prostitute. According to legend, Lupita proved her chastity by carrying hot coals without getting burned, which may be alluded to in the mention of soft coal below―though it is her sister Luperca who is being spoken of there.

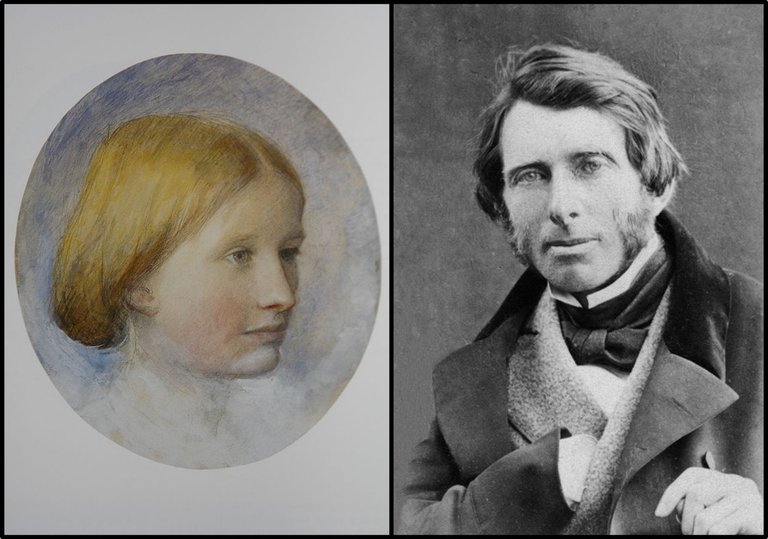

Luperca Latouche Latin: Luperca, the she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome : the wife or a priestess of Lupercus, the Roman equivalent of Pan. Rose La Touche was the pupil, cherished student and muse on whom the English art historian John Ruskin based his tract on education and culture Sesame and Lilies (1865). She was ten years old when she first met the 39-year-old Ruskin, and probably in her teens when he began a romantic relationship with her. She twice turned down his proposal of marriage, and died in Dublin in 1875 at the age of just 27. Ruskin’s intermittent insanity, which began to afflict him in 1877, has been attributed to his grief over her death.

her jambs were jimpjoyed to see each other French: jambes, legs. As her legs were always spread, they rarely saw each other. It is surprising to find so direct an allusion to James Joyce in the text of Finnegans Wake. He haunts every page of the book but is rarely named so explicitly. In the transition draft Joyce wrote: her galbs were glad to see each other. French: galbe, curve, outline, silhouette, especially the curvaceous outline of a fine figure.

Graunya ... the greatsire of Oscar, that son of a Coole Gráinne was the heroine of the Irish tale of The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne, which tells essentially the same story as Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde. She was betrothed to the much older Finn MacCool but at the wedding feast she served Finn and his guests a sleeping potion and eloped with one of Finn’s younger henchmen Diarmuid. Finn was the grandfather of Oscar and the son of Cumhail (Cool). Gráinne was also the Irish name of Grace O’Malley, the 16th-century Irish pirate queen, and the inspiration for Joyce’s Prankquean. The concurrence of Oscar and Coole also brings Oscar Wilde into the mix. The Wild Swans at Coole was the name of two collections of poetry by William Butler Yeats, published in 1917 an 1919. Coole Park, near Gort in County Galway, was the home of Lady Gregory. As we learned in an earlier article, Oscar was not the only member of the Wilde family to be mired in sexual controversy. His father William Wilde was found guilty of sexually assaulting a young woman Mary Travers.

arrah of the lacessive poghue ALP and Arrah-na-Pogue, the eponymous heroine of Dion Boucicault’s melodrama about love and loyalty, which is set against the backdrop of the United Irishmen’s Rebellion of 1798. Arrah-na-Pogue is a key text for Finnegans Wake.

she, come leinster’s even, true dotter of a dearmud Aoife (Eve), the daughter of Diarmait Mac Murchada (Dermot MacMurrough), King of Leinster. She married the Anglo-Norman warlord Strongbow (Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke) in 1170.

her pitch was Forty Steps and his perch old Cromwell’s Quarters Cromwell’s Quarters is a short stepped lane in Kilmainham, Dublin. It was popularly known as The Forty Steps. It was formerly known as Murdering Lane or Cutthroat Lane. The modern name was adopted in 1892 and refers not to Oliver but to his fourth son Henry Cromwell, who was Lord Deputy of Ireland (1657–58) and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (1658–59).

- valkirry Valkyries: in Norse mythology and Wagnerian opera, female attendants who choose fallen heroes from the battlefield and lead them to Valhalla. Possibly evoked by the allusion to Yeats’s Wild Swans:

These heavenly maidens were not first imagined by himself [Muhammad]. They are noticed in the Persian hymns, much earlier, as meeting the pious: they are the Apsaras (or “watermovers”) of the great Indian epic, who wed heroes in heaven; the Valkyries (“hero-choosers”), and swan maidens, of the Norse, which were the white clouds. ―Conder 239–240

Arcoforty Italian: arco forte, strongbow. Noah’s Ark and the forty days and forty nights are also relevant, as is his rainbow: Italian: arcobaleno, rainbow. The colours of the rainbow (iridescent huecry) are encoded in the following sol-fa musical notes: down right mean false sop lap sick dope (do re mi fa so la ti do).

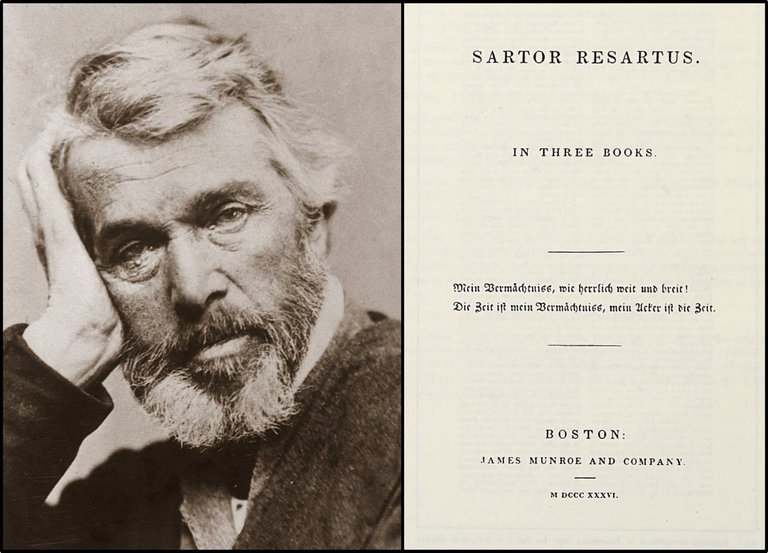

Tawfulsdreck German: Teufelsdreck, Devil’s shit. Teufelsdreck was the name Thomas Carlyle originally bestowed on the subject of his satirical novel Sartor Resartus. Under pressure from his publisher, he disguised this as the less objectionable Teufelsdröckh. This novel is another key work for Finnegans Wake.

A reine of the shee, a shebeen quean, a queen of pranks The Queen of Sheba, and the Prankquean. French: reine, queen. Rain figures prominently in both Noah’s story and that of the Prankquean. Anglo-Irish: shee_, fairy. Anglo-Irish: shebeen, an illicit tavern. Hebrew: שֶׁבַע (shebha), seven. Archaic: quean, prostitute. In Shakespeare Titania was the Queen of the Fairies, but as there is no Oberon or Bottom, she may not be relevant here―unless Oberon is the kingly man.

by the beer of his profit by the beard of the Prophet!, an oath popularly supposed to be used by Muslims. The Prophet Muhammad features prominently in Finnegans Wake (see below for further discussion).

wilde erthe blothoms followed an impressive private reputation for whispered sins? Oscar Wilde, again:

Willie Wilde [Oscar’s elder brother] came over to London and got employment as a journalist and was soon given almost a free hand by the editor of the society paper The World. With rare unselfishness, or, if you will, with Celtic clannishness, he did a good deal to make Oscar’s name known. Every clever thing that Oscar said or that could be attributed to him, Willie reported in The World. This puffing and Oscar’s own uncommon power as a talker; but chiefly perhaps a whispered reputation for strange sins, had thus early begun to form a sort of myth around him. He was already on the way to becoming a personage; there was a certain curiosity about him, a flutter of interest in whatever he did. ―Harris 1:53–54

Wild Earth is the name of a short collection of poems by Padraic Colum, his first book of poetry (1907). The title is borrowed from the concluding line of one of the poems, which is quoted in the Scylla and Charybdis episode of Ulysses :

As in wild earth a Grecian vase. ―Colum 14

Young Colum and Starkey. George Roberts is doing the commercial part. Longworth will give it a good puff in the Express. O, will he? I liked Colum’s Drover. Yes, I think he has that queer thing, genius . Do you think he has genius really? Yeats admired his line : As in wild earth a Grecian vase. Did he? ―Ulysses 184

Colum may be referenced by the phrase a column of lumps, though this is also another borrowing from Walter Hubert Downing’s Digger Dialects, meaning In disorderly military formation (Downing 17). Colum’s name―he was born Patrick Columb―comes from the Latin: columba, dove, which pairs Issy’s raven (ravenous).

Padraic Colum was born a few weeks before Joyce but outlived him by more than thirty years. He and Joyce first met in 1901 or early 1902 at one of Lady Gregory’s at homes (Mary & Padraic Colum 10). They later struck up an acquaintance in the National Gallery and remained close friends ever after (Mary & Padraic Colum 18–19).

Dogs

In Finnegans Wake Issy’s two dominant personalities are usually depicted as a dove and a raven, and both of these are present in this paragraph (soiled dove ... eyes ravenous and possibly in the allusion to Padraic Colum). But here Issy and HCE are also portrayed as dogs:

Lupita Latin: lupa, she-wolf.

Luperca the she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus.

sfidare him, tease fido, eh tease fido, eh eh tease fido Fido is a common name for a dog. Italian: sfidare, to challenge : ti sfido, I challenge you : fido, I trust : faithful. Dogs are called Fido because they are faithful creatures, but these two bitches are anything but faithful.

dug of a dog of a dgiaour, ye! giaour is a Turkish term of reproach for non-Muslims, especially Christians.

John Gordon sums up this paragraph in the following words:

67.28–69.04 [the long paragraph we are now studying] re-evokes the mirror-girl Issy as femme fatale sending ‛many a poor pucker packing to perdition’, whispering provocative messages down to her defunct old victim―dog, king, ‛ravenous’ raven-eyed blind relic of a ‛dead era’. ―Gordon 135

Islam

This passage is also replete with references to Islam, which I will leave you to uncover for yourself. Why Joyce decided to include these elements in this particular paragraph is a question I cannot answer. Perhaps the camel in the second line made Joyce think of Arabia. In The Books at the Wake James Atherton explains why Joyce drew so heavily upon the Koran when writing Finnegans Wake:

The Koran interested Joyce not only because it is one of the world’s major sacred books but also for a technical reason which made it useful for his purpose; it is not only sacred but also extremely difficult to interpret. Perhaps it has been the necessity of making a reputedly infallible book conform with all the changing needs of Islamic civilization in successive centuries that has led to the growth of the intricate science of Koranic exegesis, perhaps it is the intricacy of the Koran itself; but no book―not even the Bible―has been studied with such devoted subtlety.

Hughes’s Dictionary of Islam contains, in the article ‛Qur-ān’, a subsection purporting to give a brief outline of the ways in which the Koran has been explained. This summary, which Hughes declares to be exiguous and inadequate, contains well over a thousand words. But, since there is a possibility that Joyce read it and used it, I will give here an even more exiguous summary of Hughes’s ‛brief outline’, aiming at exemplifying the intricacy of the system rather than explaining its intricacies:

(1) The words are of four classes: special, hidden, ambiguous, and complex.

(2) Sentences are of two kinds: obvious and hidden.

(3) Obvious sentences may be clear, explained, technical, or incontrovertible.

(4) Hidden sentences may conceal a second meaning, may have two obvious but incompatible meanings, may display a whole variety of meanings, or may have no meaning that any human intelligence can grasp.

(5) There are four levels of meaning. They are literal, figurative, palpable, and metaphorical.

But this last point is subject, Hughes tells us, to debate; and he adds that some Islamic scholars maintain that there are more than four levels of meaning. The alternative usually put forward is seven, but other larger numbers have been suggested. This business of finding multiple meanings in a sacred book is an ancient and reputable occupation for scholars which must have been well known to Joyce. Several years have gone by since Professor Levin first suggested in his pioneer book, James Joyce, A Critical Introduction, that the four levels of meaning which Dante declared to be present in the Divine Comedy were present also in Finnegans Wake. It now seems certain that this is true; but with Joyce’s customary ‛toomuchness ... fartoomanyness’ (122.36), it also seems certain that there are more than four levels, and that one of the purposes, and the results, of the slow process of accretion that produced the Wake was the addition of more and more levels to the literal foundation. ―Atherton 207–208

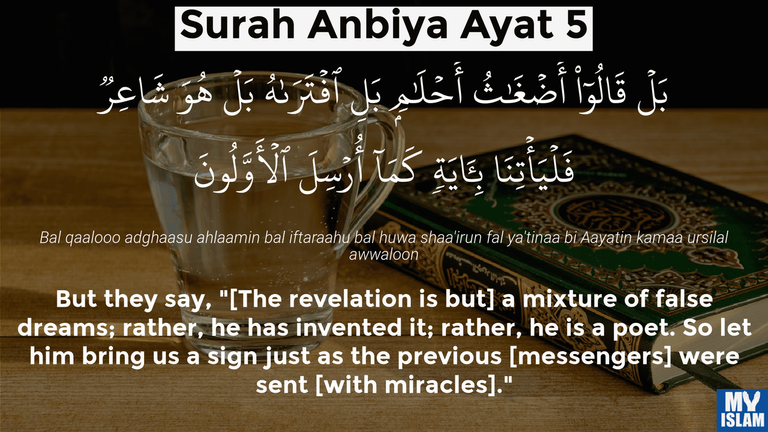

Surah_ 21, The Prophets―possibly alluded to in this paragraph (by the beer of his profit)―contains the following verse, which might just as easily be said of Finnegans Wake:

Yet they say, “This [Quran] is a set of confused dreams! No, he has fabricated it! No, he must be a poet! So let him bring us a [tangible] sign like those [prophets] sent before.” ―Mustafa Khattab, The Clear Quran 21:5

A Few Loose Ends

à la zingara in the manner of a Gypsy. This evokes a cluster of Romani terms towards the end of this paragraph, which Joyce took from George Borrow’s dictionary of the Romani language.

Tomar’s Wood The Norse name for a wood that once stood in the vicinity of the modern Phibsboro and Drumcondra. During the Battle of Clontarf Brian Ború’s forces were stationed here.

I’ll close with a quotation from Finnegans, Wake!, an online blog maintained by a group of enthusiasts from Austin, Texas, which is always worth a glance or two:

Nor needs none shaft ne stele from Phenicia or Little Asia to obelise on the spout, neither pobalclock neither folksstone, nor sunkenness in Tomar’s Wood to bewray how erpressgangs score off the rued.

It is a very dense and difficult sentence to unpack, but there are some good clues in there. That word stele refers to a type of ancient monument, a stone slab with inscriptions. You’ve got an obelisk, another monument, in there. The portmanteau word pobalclock combines two Irish words which basically translate to folk-stone and there is folksstone following right after pobalclock. FWEET mentioned that there is a stone pillar monument in the town of Folkestone in England marking the spot where Saxon invaders landed on the shores. You see where this is going? The sentence essentially says we don’t need monuments to mark where the invaders landed, we don’t need to recognize those erpressgangs―a word combining the German erpressen meaning to blackmail or extort and also press-gangs which were groups that kidnapped men and forced them to enlist in the military. ―_Finnegans, Wake!

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- James S Atherton, The Books at the Wake: A Study of the Literary Allusions in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1960)

- George Borrow, Romano Lavo-Lil: or English Gypsy Language, John Murray, London (1888)

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Mary & Padraic Colum, Our Friend James Joyce, Doubleday & Company, Inc, Garden City, New York (1958)

- Padraic Colum, Wild Earth: A Book of Verse, Maunsel & Co, Limited, Dublin (1907)

- Claude Reignier Conder, The Rise of Man, John Murray, London (1908)

- Walter Hubert Downing, Digger Dialects: A Collection of Slang Phrases Used by the Australian Soldiers on Active Service, Lothian Book Publishing Co, Melbourne and Sydney (1919)

- John Gordon, Finnegans Wake: A Plot Summary, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, New York (1986)

- Frank Harris, Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions, Volume 1, Frank Harris, New York (1918)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Number 3, Shakespeare & Co, Paris (1927)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

Image Credits

- Romulus and Remus (detail): Peter Paul Rubens (artist), Musei Capitolini, Rome, © Sailko (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Null-Null: © Florian Hardwig (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Rose La Touche: John Ruskin (artist), Ruskin Foundation, Ruskin Library, University of Lancaster, Public Domain

- John Ruskin: W & D Downey (photographers), National Portrait Gallery, London, Public Domain

- The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife: Daniel Maclise (artist), National Gallery of Ireland, Public Domain

- Cromwell’s Quarters: Irish Capuchin Franciscans (photographers), Irish Capuchin Archives, Public Domain

- Thomas Carlyle: Elliott & Fry (photographers), Public Domain

- Sartor Resartus: James Munroe and Company, Boston (1836), Public Domain

- Padraic Colum: © University College Dublin, UCD Library Special Collections, Creative Commons License

- Luperca: The Capitoline She-Wolf: Capitoline Museums, Rome, Jastrow (photographer), Public Domain

- Quran 21:5: © My Islam, Fair Use

Useful Resources

- Cromwell’s Quarters

- FWEET

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- Joyce Tools

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive

- From Swerve of Shore to Bend of Bay

- John Gordon’s Finnegans Wake Blog

- James Joyce: Online Notes