Connection, a Crisis of Modernity:

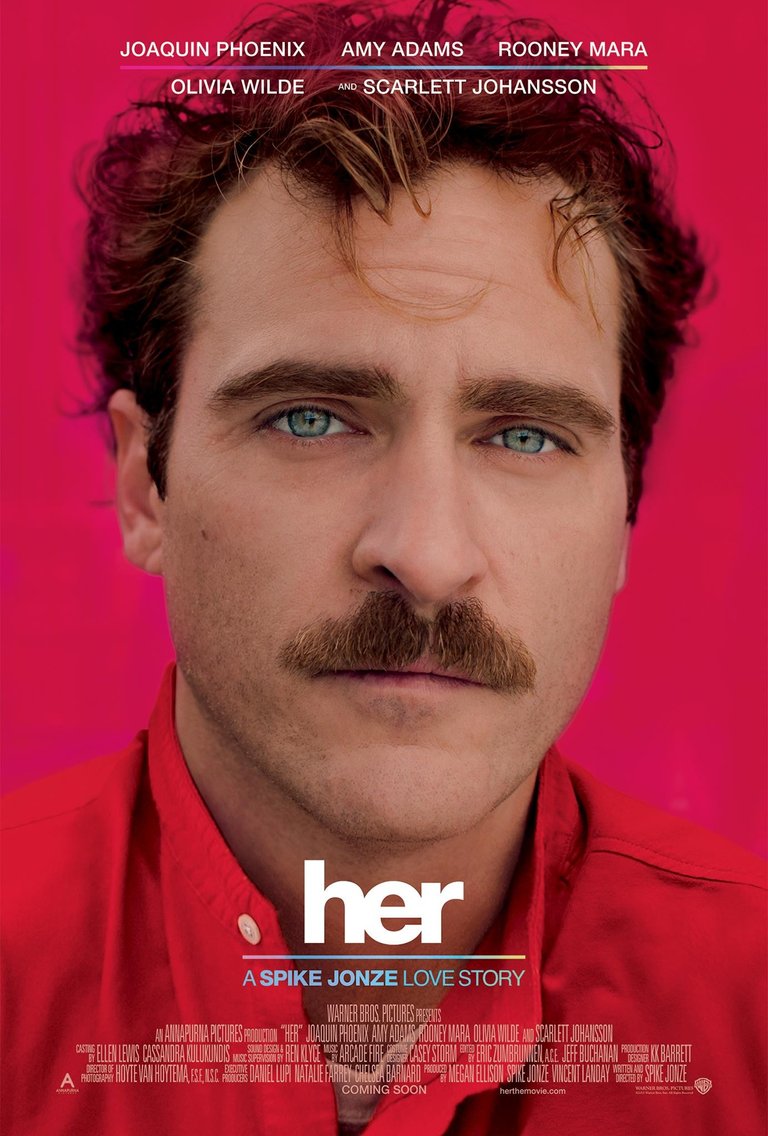

Her (2013, Spike Jonze)

In the modern world, social media and the Internet allows the ability to connect with others, facilitating an almost infinite degree of instantaneous connections with virtually anyone in the world. Message-boards and Walls have become the digital manifestation of the agora, allowing people a free place to come together and communicate, despite the corporeal happenstance of geographic location. At the very least, that is the ideal. The manifestation of such a technological system denotes a world in which social intimacy and communication are of prime importance.

From the very outset of Spike Jonze’s exceptional film Her, it is clear that his primary thesis is about the pursuit of human connection, of real intimacy, and the desire not to feel alone in the increasingly isolating modern world. The very first shot depicts Theodor Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix), his moustachioed face filling the screen, as he gazes at us in the eye, speaking—almost whispering—deeply personal words of endearment, of intimate romance.

Despite their apparent closeness, however, the words are revealed to be mere artifices of commodified intimacy: he is not serenading us, but is instead dictating a letter to a computer screen. Theodor, along with many other writers, works at Beautiful Handwritten Letters (.com), a company with the sole purpose of outsourcing and manufacturing intimacy, of impersonal personalization as a form of revenue, selling semblances, facsimiles of relationships on demand over the Internet.

Meant as tool of connection, technology is actually disconnecting us from our selves and others, digitally dividing us. Imperfections are hidden as people create avatars of themselves, manufacture perfect versions that obscure their flaws—flaws that make us innately human. Interaction on the Internet thus loses meaning, becomes insincere and vacuous, as genuine intimacy becomes lost between all the noise of the countless connections it facilitates; there is only so much one can truly share with others, and not enough of oneself to go around.

Theodore is no different: desperate for intimacy, he seeks it out—be it with disembodied voices on adult chat services or an advanced operating system—taking comfort in the false intimacy of anonymity that technology provides. At the same time, he shies away from any form of personal attachment, preferring—or perhaps imposing—isolation from the outside world and others, paradoxically seeking this candid contact in technology.

Perhaps it is understandable, considering his divorce, that Theodore feels unable to share himself, to commit to someone on such an intimate level again. He lives in the past, in memories, in which he shared a happy life of intimacy with another human being, his wife Catherine (Rooney Mara), yet his present is plagued with the psychological trauma of disconnection. Theodore perpetually forces himself, in some amalgam of masochism and hyper-retrospection, to confront his own glaring personality faults that made him impossible to live with. This sends him deep inside a fathomless abyss of disconsolation, blinding himself to the fact that he might not be solely to blame.

Just as his wife could not bend herself into his perfect ideal of her, neither could he for her—it was mutual disconnection that divided them. She is too willing to apply the blame, and he is too willing to accept it, yet neither are able to live up to the ideal they have of each other—the avatars of perfection they project on each other are not genuine, so instead of embracing the imperfection, they reject it.

In his complete isolation, Theodore turns to technology for intimacy instead of a living-and-breathing person. Perhaps, as Catherine says, it is because he does not need to commit to it as much, for he can turn it on and off as he pleases. Perhaps, it is because the weight of expectation to live up to ideals is moot in the comfort of anonymity.

Instead, he finds companionship with an Artificially Intelligent Operating System, Samantha (Scarlett Johansen), a self-aware computer program trying to learn for itself what it means to be human, and what it means to love. As she intimately whispers into his ear from his earpiece so only he can hear, Theodore, having lost a part of himself in the divorce and desperately alone, seeks out connection, wanting somebody to want him, to share himself with someone else unconditionally again—for sharing a life with someone else allows one to be more than just oneself.

In the end, it is the capacity of the Samantha to make sincere connections better than humans—to love to the extent that one human is not enough, to be truly intimate with more than one person—that ends Theodore and Samantha’s budding relationship. For them as well, it is the ability to connect that disconnects them.

Technology has vastly increased our ability to communicate with each other, enabling the ability to share our personal interests with others that supposedly appreciate us for who we are. The internet allows this assertion and display of one’s own sense of self in a space removed from the judgemental eyes of our peers—there is an overwhelming sense of freedom that this practice provides.

However, all those people of innumerable differences share one thing: the soft, unnatural, blue-tinged glow of a computer screen whitewashing their features as they seek connection alone in a room, allowing technology to mediate a fake representation of themselves. While the internet fosters connection, it also breeds isolation.

Her is a film that is intimately human, obsessed with our human desire to connect to each other, to be intimate on a personal level, separate to the pseudo-connection that technology provides to countless carefully constructed facsimile versions of people. Ultimately, the desire to share ourselves with other people, to be loved and accepted despite our imperfections, is what we as humans crave. The desire for intimacy and connection that only corporeal contact can provide—despite our “weird, gangly, awkward” parts—is what makes us human.

Indeed, there is certainly something to say about how another person’s head fits so perfectly, nestled on one’s own shoulder.

This will hopefully be the first of many weekly film essays or "reviews" under the Major Screen Time banner, so I hope to see you next time!

I wrote about my love of film and my plans for MST in my Road Ahead introductory articles. I know, I know, this isn't what I said would be next, I'm still working on that—to be honest, I watched Valerian and, though quite exciting, I didn't find much to feel inspired about.

But, I think I've come across an idea for a subject worth writing about.

Here's a working title:

Juxtaposé - Luc Besson’s Pulp Sci-Fi and the Dirge of Meaning: The Fifth Element & Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets

(I reserve the right to change my mind on the subject).

Juxtaposé is a series I'm working on that compares two films, be it in the same genre, the same director, or similar thematic concerns, in order to see how each informs the other.

Until then, however, I'll see you in the comments!

This movie have been in my list since it came out, I need to watch it.

Incredible post Major!

It is certainly one of my absolute favorite films, I highly recommend you watch it, it's truly beautiful.

I am trying to make up my mind:

are you a film critic/ lover or a poet? You certainly know how to make words look beautiful. I hope there are enough people out here who can actually appreciate this kind of writing. I know I can, although I myself am more of a storyteller.

I enjoyed this film a lot too, for many reasons, included it in a list in one of my previous posts - check it out here if you're interested - as it's one out of my couple of hundred favorite movies ;>)

I am looking forward to your future posts and your juxtaposé series. I am glad to have discovered your work.

Let's try to stay in touch!

Thanks so much for your kind words! I glad you enjoyed it. I like to think of all writing as storytelling, all art for that matter—most importantly though, all good stories must be affective on an emotional level. I write fiction too, you're more than welcome to peruse some of my other posts if you wish :)