SORCERERS OF KIA

BOOK ONE OF THE KIA CHRONICLES

By

Petro Lukasido

The Continent of Naku

For Anna and Joachim,

And all young lovers of history and myth.

PROLOGUE

“From the hand of Baltora, the maker of laws,

Was I, Kannu Assham, given these statutes and ordinances.

I, the blood of Mash and Lut,

The son of he who banished the Serpent of Void,

Even I, the God-fearing Prince, was raised to kingship within these walls of Khozron;

As Khozron reigns over the Twin Rivers,

So I reign over the king of cities, mighty of ramparts,

That as the Heavens are ordered in the hierarchies of Gods and spirits,

So, too, shall Khozron be ordered, that all may dwell in concord.

Let good men rejoice in these just laws,

And may the gifts of Albarak, the All-highest,

Never desert them and their kindred,

And may the eternal sleep of Elon

Be far from them until ripeness of age.

Let evil men tremble, for their condemnation is right.

Let them pay in kind for their offenses

According to the Laws of Baltora, Lord of Justiciars.

Their fields shall be barren, and their market stalls without custom,

For they shall be marked for destruction

By the gods they have mocked.”

- From the opening proclamation of the Law Stele of Kannu Assham I.

Chapter One

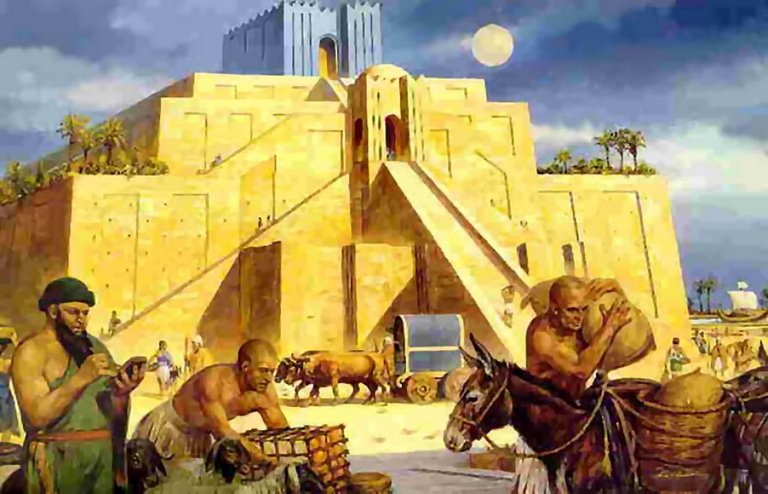

A clamor arose within the walls of Khozron. Not the clamor of famine or mutiny, nor that of war or siege. Such horrors were confined to the past, the subjects of legends and children's tales. This clamor was festive, anticipatory. A monumental celebration was only hours away, to mark twenty years of Khozron's venerated King sitting the throne of his grandfathers. Priests bathed their hairless flesh in lustral baths as merchants raised their booths in every lane and alley. Farmers led fatted sacrificial cattle to the looming ziggurat as mothers tried to reign in unruly naked children from running in front of carriages. Slaves hauled litters and horses drew supply carts from far and near past the multi-colored lamassu that stood sentry at the city's ten gates. King Sarban Omer, the second of the name, spared no expense to make this feast one for long remembrance in yet unwritten songs.

The fourteenth day of the Offspring moon was reaching its zenith. When the night approached and the High Priest announced the sighting of the night orb in her fullness, the ceremonies would begin in earnest. Royal decrees carved in clay and mounted in all public spaces declared that the king would dedicate a cult statue of Lut, newly cast from finest silver, to be housed in the Holy Place atop Khozron's seven-tiered ziggurat. Further, for the five days which followed, the meat of all sacrificial victims would be shared by inhabitants of all classes including visitors, mock chariot battles would be staged, and the services of the moon goddess's priestess-whores would be offered at half the regular price.

A curse for both granary and treasury, Yakim thought, amused, when he read the decree last month. He was a sail maker by trade, an employee of the most sought after shipwright in the city’s shipping guild. From fishing skiffs trolling the sacred twin rivers to the invincible triremes of Parthos, their work was sought out by sailors from all corners of Kia, and fetched handsome commissions to match. He and his patron acquired a sizeable fortune together, and were enriched further when ordered to construct the pleasure barge which his guild would present to the King when he came to bless the river Gireth.

Yakim stood beside the docks, a cord away from the city’s northeastern gate. A small gust inflated the ship’s single sail, displaying the masterful stitch work of its maker. Two months he and his partners labored to put together a sail of multi-colored linen while Ashur’s underlings assembled the oversized barge before him of imported pine and pitch. The result he found underwhelming, more decorative than functional. There were only ten oar slots: five on the port side and five on starboard, indicating that it was built for a leisurely sail along the river’s currents. Elegant painted carvings of shedu and cavorting nude boys and girls appeared to handle the round slots as if playing at ball. Those would undoubtedly create resistance from the water, Yakim thought, bringing the craft’s speed somewhere between leisurely and painstaking. He could not deny its beauty, however, nor did he think that the King would be anything but flattered; there would even be a substantial gift of gold and silver given to the guildsmen as a sign of gratitude. Doubtless my Layla will want a portion of my share, he told himself, stifling a laugh.

Rhythmic footsteps pounded behind him. A sedan chair draped in cream-colored tree wool approached, born by four sun-withered slaves in linen kilts. Wealth and fine foods had softened Ashur, and had fattened him to the point that even walking short distances robbed him of breath. The bearers halted and rested the chair not far from where Yakim stood. As he watched the portly shipwright struggle to keep his balance while stumbling out of the sedan supported only by a cane, the sail maker could only smile and shake his head.

"Truly, my friend,” the awestruck Ashur rumbled as his beady eyes examined their creation, "this vessel is our finest work to date. And our most expensive."

"Fine work indeed," said Yakim, running his palm across the bosom of a carved dancing girl, "and no doubt the guild’s coffers are the emptier for it. But our finest? I can think of finer!"

Ashur raised an eyebrow. "Any larger, and this barge would be ready to stand against even the Parthic fleet..."

"Half of which we also built," Yakim interrupted, thin lips turned in a knowing half-grin. "Surely you haven't forgotten? Or the barge of the Goddess-Queen of Gebmaat, so much grander than this one? Those were works worthy of remembrance! This," he frowned, turned to the garish thing, "is a toy, meant only to open the doors to greater favor with our God-fearing King."

The shipwright steadied himself with his cane. "Then, you will decline your share of the King's gratuity, old toad?" He laughed. "I should not envy you when you return to Layla empty-handed!"

Yakim’s grin turned from knowing to confident. "When I return to my wife and children, Ashur, it will be with both hands full, if the gods will favor my wager on the chariot battle."

Ashur shook his jowls, incredulous. "You? Gamble? I never took you for such foolishness, Yakim! Surely, you were not dense enough to bet your entire share?"

"Had I done that," Yakim said, "I might as well hand Layla the very knife with which she'd geld me! I bet a quarter talent, no more."

"Even so," said Ashur, "you would not bet so much if you did not have some idea of the victor already. You’re a cautious man, always were.” He dropped his voice to a loud whisper. “Whom do you support? Perhaps it is not too late for me to place a wager."

Yakim walked closer to his employer. "My friend, Hashbaz was recently elevated to the rank of Grand Captain of the King's chariot host. No man between the rivers can drive horses or maneuver as well as he. And he competes in the mock battle tomorrow at midday.” He folded his arms over his chest. “It promises to be the surest bet I’ve ever made.”

Ashur could not help but notice the impetuous gleam in his friend’s eye, the surety in his voice. Yakim was never wont to take chances this recklessly, he thought, unless he was certain of victory. “If the gods favor you,” he sneered, with a wave of his hand. “I must be off now. The courtyard of the ziggurat will fill before long. I must secure a good place to view the opening sacrifices when the moon appears. You would do well to follow, if you do not want to stand with workmen and slaves from the city walls.” The shipwright turned ponderously on gout-stricken feet, wincing as if tiny glass-shards were lodged in all his parts below the calves. Two slaves helped lift him into the waiting sedan. All four lifted their pole ends, then trudged back to the gate.

Yakim chuckled as he watched the sedan grow smaller in the distance. A life of luxury has done you no favors, old friend, he thought as he followed on foot to his own home. A decade ago, the short walk to the Gireth docks would have taken no time and small exertion. People can change so drastically in such a short time – in body, if not in mind. But in spite of all, Ashur was still the same jovial and boisterous companion he had known since his boyhood. They were opposites in most ways: Ashur shaved his head clean, whereas Yakim kept his pitch-black locks cut short, as was the normal style for spring and summer. The shipwright favored bright colored worm silk and gemstones about his fingers and neck, but the sailmaker preferred a plain linen tunic and a leather apron, except on feasts. More subtly, Ashur liked to spend his wealth on ornament, food, and slaves. Yakim - who made only slightly less than his patron - sent his son Kish to be a scribe’s apprentice and bought gifts for his wife and daughter. The surplus he kept, setting what was left aside for Hoba’s eventual dowry. The rest his wife and son would inherit when Elon called him to the Great Abyss.

Tents of linen and tree wool were set up before mud brick storefronts along the city’s market street. The road was packed dirt, three times as wide as any other in Khozron, enough for three men and two wagons to walk abreast. Tantalizing smells of charred meat and foreign spices danced through Yakim’s nostrils, reminding him of travels to distant lands. As he paused at the stall of a woman selling goat meat and fish on wooden skewers, he remembered the fishermen of Toros, the largest of the Parthic cities, crying their morning catches in crowded streets amidst painted marble colonnades. All he ate in Toros was fish and olives, he recalled, along with some queer kinds of sea insects which the cooks had to boil alive. He handed the woman a fistfull of copper coins, picked out two skewers of goat and one of fish to take to his family. The woman wrapped the skewers in a sheet of leather, tied the bundle with hempen twine, and handed them to Yakim with two coppers to spare.

The road inclined gently upward. At its apex, Yakim could see a short distance off the Royal Palace and its water gardens, verdant in spring’s raiment of leaf and flower. He sighed. This part of the city he found the most beautiful, and the equal of it he had never seen elsewhere. Pylons of blue-painted brick guarded the entrance like sentinels, crowned with crenellations of solid gold (or, so the appeared). Pools shimmered here and there, reflecting statues of gods and mortals alike. Birds sang as they bathed and spread wings of many hues to fly away again as reclining nobles clad in fine robes and tall hats enjoyed their wild music. Such birds as he had seen in Erling to the east could say words in five tongues in praise of a maiden’s beauty for a price, but even they could not compare to all the art and finery with which King Sarban Omer surrounded himself.

Further on, he glimpsed the common house in which his family lived off to the right, with a commanding view of the gardens. Yakim was one of few men in Khozron wealthy enough to raise his offspring in the sight of the palace – an honor that in his grandfather’s day was reserved only for nobles or priests. He hoped that Kish, as a scribe, would do even better, dwelling under the King’s own roof. This would be his son’s fourteenth summer; he was now a man grown, of an age to begin contemplating a suitable match. Ashur has daughters, he remembered. One of them, perhaps? His reverie was disturbed by the sight of a crowd to his left. A lanky, sunken-eyed, brown-skinned man in the black and white robes of Elon’s priesthood was plying his magic tricks (for, surely, actual sorcery was more dangerous than this man’s antics) while standing on a wooden crate. He made flame appear from his bony fingers, then unite into a scintillating sphere. The crowd cooed as the hovering fireball changed shades from orange to blue to green, then to purple and black, then back again through all colors so rapidly that they could barely be distinguished.

The priest threw out his hand, propelling the ball toward a maiden among the crowd, a slip of a girl no older than seven or eight. She was naked, as were most children her age during the spring and summer months, wearing only a beaded necklace and a gap-toothed yawn of amazement as the orb danced about her like a dragonfly. Yakim was taken aback by how much she resembled Hoba, his daughter. They were of an age, with the same almond eyes, snub nose, and wild black curls. The next moment, the fireball consumed her, bathing her from head to foot in a lambent golden blaze. A woman screamed. The onlookers mumbled as one, watching the poor thing cooked before them. For a moment, Yakim thought they would tear the man apart themselves – rightfully so, if he had truly done the child to death. Curiously, however, she never once cried or screamed or let out any indication of pain. And would there not be a smell of charred flesh? The sunken-eyed priest clapped his hands. The flames petered out, leaving a black mark upon the street where the naked maiden once stood. There were no bones, no ashes, and no moisture: nothing to suggest a living creature had stood in that same spot and burned to death a moment ago. The shouting of the crowd turned to susurrus, then to silence. Heads turned again toward the box and its occupant. From behind him stepped…the immolated child, whole as she was before. With a smile as luminous as the flames and a deep bow, she and her master (no doubt, the two were in cahoots for this act) accepted the onlooker’s offering of shouts, applause, and thrown coins.

Yakim was less impressed. Conjurers and petty fortune tellers of this sort were as common as fleas in the ancient streets of Gebmaat. Three hundred years ago, however, such servants of death dealt in blood spells and sacrifices of human flesh to satisfy their hungry god in this very city. Kannu Assham, the first king of a united Khozron empire, exiled the priests with the help of two armies: one armed with swords and spears of bronze, the other armed with sorcery. The priestesses of Lut, the goddess of the moon, pledged their loyalty to the King-to-be; he only had to wed their High Priestess and place the city under their Lady’s eternal patronage. Elon’s priests were banished to the deep desert, and the god of death was only ever mentioned again in rites for those who have passed the veil. All to the good, Yakim thought. Better priestess-whores in the service of a righteous ruler than sorcerers terrorizing their people into obedience. He spat upon the ground in contempt and passed by the ridiculous scene, pressing on to his home.

The common house was a dun brick rectangle of three stories housing six other families. The facade was plain, but the dwellings were larger than most and more costly than half of Khozron could hope to afford. Windows faced in all directions, covered with leather blinds. Up side steps to the third floor and through a hallway, Yakim opened his apartment’s boxwood door. Kish, flat of belly and long of limb, sat on a cushion under the eastern window, reading to Hoba from a tablet he had copied that day in scribal school. From the little he overheard, it was the tale of the twin gods Gireth and Pishtim and how their blood fed the sacred rivers. Kish broke off as he heard the door, looked toward his father with round, soft eyes. Not for the first time, Yakim noticed how his son had inherited the eyes and face of his mother and the body of his father, whereas for his daughter the traits were reversed. Hoba squealed for joy at the sight of the leather bundle. She could tell they would have goat tonight, a welcome break from the usual meal of bread, porridge, and barley beer. In the corner of the sitting room, not far from the stove, sat Layla at her wheel, spinning wool for yarn. She stood, grinned, bowed. “Welcome home, husband,” she said. “Is the pleasure barge to your liking?”

“I had little enough to do with its making,” Yakim said as he closed the door behind him, “but I’m sure to get a lovely share of the King’s gratuity all the same. Three talents of gold and one of silver for each guild master! With a dowry like that, Hoba could almost marry a price. Or the Bael of a client city, at least!”

“I don’t want to marry a prince or a ‘bay-ul,’” Hoba interrupted, tossing black curls from side to side as she shook her head. “I want to marry a scribe like Brother. Then he can tell me stories and take me to festivals at the palace!” She crossed her tiny arms: apparently, that decision was final.

Layla chuckled. “She has been listening to Kish tell stories since he got back from the school,” she said. “If we aren’t careful, she’ll learn to read herself. What use would a scribe husband be to you if you learned all his skills yourself, little rabbit?”

“He could write stories and songs about me, too,” she said. “They would sound silly if I wrote them.”

Layla agreed and beckoned for her daughter to come to her. Hoba leapt up from her cushion and ran into her mother’s arms, buried her face in her abdomen. Childbirth did nothing to change Layla’s beauty, Yakim reflected with a stroke of his chin. Her hips were wide, her bosom bountiful: the perfect shape and figure for giving life. Her raven hair was tied behind her head and one could just make out the curve lines of her body beneath the long linen skirt she wore.

Kish rose, bowed to his father, and took the bundle from his arm. A blanket, plates, and cups were set in the center of the room, the skewers and a pitcher of beer in the center of that. The customary portion of goat and fish was placed in a bowl before the household shrine above the stove, and the family took their meal, seated on the floor. “Master Jerubal gave us tomorrow as a holiday,” Kish said to his father as they all finished. “Will we be allowed to go see the chariot race? Or the dedication of the statue?”

Yakim wiped grease from his mouth with the back of his hand. “You can see the statue itself in the square today if you really want. I passed it this morning on the way to the docks. Quite a sight to behold!”

Kish’s face brightened. “Could I go? By myself?” This would be the first time Father had let him go anywhere on his own.

“Well, that wouldn’t be fair to your sister, would it?” Yakim said. “Maybe she wants to see the statue.” He shot Hoba an inquisitive glance. “Do you want to see the silver Lut statue before it goes into the Holy Place tomorrow?” Hoba nodded. Kish twisted his mouth; this had not been the arrangement he had in mind. “Let us make a bargain, son,” continued Yakim. “I saw a few tablet sellers and scroll mongers along the market street as I came home. If you take Hoba with you, I’ll give you twenty coppers to spend while you’re out.”

The boy’s face was bright again. The prospect of new tablets and scrolls to read and copy excited him enough to be shackled to his sister for an evening, though Kish was nothing if not a shrewd bargainer. “Could you give me a silver to spend?” he asked.

Yakim was sipping his beer as his son made his counteroffer. He coughed when he heard it. “A silver? By Mash’s disk, boy, how many more scrolls do you need? You’ve already copied all of old Jerubal’s cache, from what he tells me! I’ll give you fifty coppers, but that is all. You can get two or three good ones for that price.”

Kish was not appeased. “A silver,” he replied. “I’ll even buy something nice for Hoba and bring you the change.” That ought to put a little honey on the deal, he thought.

Yakim looked to his wife, hoping for support. Layla only shrugged. He returned his gaze to Kish, who was all innocent smiles and supplicating wide eyes. “A silver,” he acquiesced. “Buy your sister a new necklace or bangles or something. Just pick up the dishes and blanket before you leave.” Kish rose, hurried about to his task. “Just remember: do not spend all of my money on tablets!”

Ours is one continued struggle against degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the European, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir, whose occupation is hunting and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with, and then pass his life in indolence and nakedness.

- Mahatma Gandhi

Congratulations @petro-lukasido! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCongratulations @petro-lukasido! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP