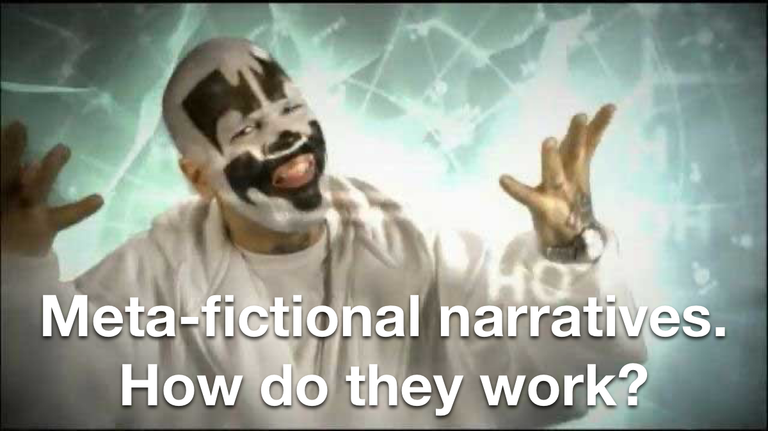

In fiction, an Unreliable Narrator gives a skewed or subjective version of events from a character’s perspective.

Now, with the dumbing down of television, we introduce a new concept called Unreliable Teleplay to deal with this.

In theory, an Unreliable Teleplay allows for creative flexibility, where the audience can appreciate different versions of a story while understanding that they may not be entirely accurate or consistent.

There's this thing about fiction. Fiction can itself have fictional stories within fictional stories. If you don't like a show that expands the continuity of another show, or even just a one-off episode you don't like, then that content can become fiction within the fiction.…

— Vs. Super Inertia (@inertia186) August 24, 2024

This is a variation on saying "It's Just a Show." But instead of dismissing the entire story, we allow the characters to effectively say "It's Just a Show," in-universe.

Here’s a table that captures the concept of "It's Just a whatever" from the perspective of various works of fiction, tailored to fit their unique contexts:

| Work of Fiction | Phrase | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Star Trek | "It's Just a Holo-Novel." | Reflects the series' use of holo-decks, where characters might view dramatized or fictionalized versions of events. |

| The Legend of Zelda | "It's Just a Legend." | Fits the series' mythic and cyclical nature, where each game’s story is treated as a legendary tale. |

| Battlestar Galactica | "It's Just a Myth." | Resonates with the show’s themes of prophecy and repeating history, suggesting events are part of a larger mythos. |

| Stargate SG-1 | "It's Just a TV Show." | Works in contexts where the show acknowledges its own fictionality, especially with meta-elements like Wormhole X-treme. |

| Watchmen (Alan Moore) | "It's Just a Comic." | Could reflect the meta-commentary within Watchmen, where a comic book within the story mirrors the main events. |

| Discworld (Terry Pratchett) | "It's Just a Story." | Matches Pratchett’s meta-narrative style, where characters are often aware of the storytelling conventions they inhabit. |

| Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy | "It's Just a Guide." | Reflects the absurd and self-aware nature of the series, where the Guide itself is an unreliable source of information. |

| The Sandman (Neil Gaiman) | "It's Just a Dream." | Fits the series’ exploration of dreams and stories, where events are often metaphorical or symbolic. |

| The Matrix | "It's Just a Simulation." | Ties into the film’s exploration of reality and illusion, where what’s perceived might not be real. |

| Sherlock Holmes (Various) | "It's Just a Case File." | Could be used to downplay the dramatization of events in Watson's written accounts of Holmes' adventures. |

| Doctor Who | "It's Just a Timey-Wimey Thing." | Acknowledges the show's playful approach to time travel and the often inconsistent nature of its timeline. |

| Inception | "It's Just a Dream." | Reflects the film’s exploration of layered dreams and the ambiguity of what is real and what is imagined. |

The key here is that we as audience members are not the ones who say the phrase. The characters in the work of fiction are saying this about what we consider bad writing or problem areas of and episode or iteration they supposedly remember in their own narratives.

Applying the Unreliable Teleplay: The Hologram Puzzle in Star Trek: The Next Generation

One intriguing example that highlights the usefulness of the Unreliable Teleplay framework is the hologram scene from the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Inheritance." In this episode, Data encounters a holographic message from his creator, Dr. Noonien Soong, which inexplicably knows that Juliana, Soong's wife, has left him. The perplexity arises because Data provides almost no information that would lead the hologram to this conclusion—he merely refers to her as "Dr. Tainer" instead of "Mrs. O'Donnell."

This raises the question: How could the hologram possess knowledge of events that occurred after its creation? The simplest answer might be that it's a writing oversight—a plot hole that the writers didn't fully address. However, by applying the Unreliable Teleplay framework, we can find an in-universe explanation that enriches the narrative rather than detracts from it.

The Unreliable Teleplay Solution

Under the Unreliable Teleplay concept, we consider that the episodes we watch are themselves dramatized adaptations of historical records within the Star Trek universe. This means that any inconsistencies or seemingly inexplicable events are the result of creative liberties or errors made by the in-universe creators of these adaptations.

In the case of the hologram's knowledge, the Unreliable Teleplay suggests that the version of events we see is not a perfect representation of what actually happened. Perhaps the historical records were incomplete, or the dramatization added details for emotional impact. The hologram might not have had such precise knowledge in reality, but the teleplay exaggerates this for the sake of storytelling.

Embracing Narrative Flexibility

By accepting this framework, we allow for a flexible narrative that can accommodate future retcons or expansions without being constrained by earlier inconsistencies. If a future episode or series revisits this event with a different explanation, it doesn't contradict the established lore because the original portrayal was already a dramatized, and potentially flawed, version of events.

This approach aligns with how characters within Star Trek often engage with holo-novels and simulations—stories within stories that may not be entirely accurate. Just as a holo-novel might take liberties with historical figures or events for dramatic effect, so too might the episodes we watch.

Turning Flaws into Features

The Unreliable Teleplay doesn't just excuse inconsistencies; it transforms them into opportunities for deeper engagement. Viewers can analyze and debate these narrative quirks, much like historians discuss discrepancies in historical texts. It adds a meta-textual layer to the viewing experience, where the audience participates in the construction of the narrative's reality.

Thus, this hologram puzzle isn't a detriment to the story but an invitation to explore the complexities of storytelling within a fictional universe. It encourages us to consider how stories are told and retold, both in our world and in the worlds we create.

Potential Drawbacks of the Unreliable Teleplay

While this Unreliable Teleplay framework may offer an alternative lens through which to view and interpret fiction, let us also touch on the potential drawbacks that come with this approach.

- Audience Confusion and Disengagement - When a narrative, either intentionally or unintentionally, blurs the lines between its internal reality and fiction within its world-building, it can lead to confusion and fatigue. Viewers may struggle to discern which events are "canonical" within the story and which are dramatized or exaggerated. This ambiguity can make it difficult to follow the plot or invest emotionally in the characters, potentially leading to disengagement.

- Erosion of Trust in the Narrative - Trust in the suspension of disbelief is a crucial component of storytelling. If audiences feel that the narrative consistently misleads them without sufficient payoff, they may become skeptical of future developments. This rug-pull can diminish the impact of plot twists or emotional moments, as viewers might assume that events could later be entirely invalidated or reinterpreted.

- Inconsistency and Continuity Issues - The flexibility of the Unreliable Teleplay can inadvertently introduce inconsistencies within the story. While the framework allows for reinterpretation of events, it can also result in contradictions that disrupt the internal logic of the narrative. Maintaining a coherent continuity becomes challenging when past events might always be subject to change or recontextualization.

- Difficulty in Delivering Satisfying Resolutions - Crafting a fulfilling conclusion is more complex when the narrative foundation is unstable (be it intentionally or unintentionally). If key events or character developments are later revealed to be dramatizations or misrepresentations, it can leave audiences feeling unsatisfied. A resolution that doesn't adequately address the unreliable elements may come across as incomplete or unearned.

- Overcomplication of the Narrative - Adding layers of meta-commentary and self-referential elements can overcomplicate the story. While depth and complexity are often desirable, there's a fine line between a richly woven narrative and one that is merely convoluted. Overcomplication can make it difficult for audiences to grasp the core themes or messages of the work.

- Potential Undermining of Themes and Messages - The Unreliable Teleplay might inadvertently undermine the story's themes or moral lessons. If significant events are later deemed unreliable or fictitious within the universe, the impact of those events on the overall message can be diluted and thus weaken the thematic resonance of the narrative.

Embracing the Unreliable Teleplay requires a delicate balance. Creators should aim to maintain clarity and coherence even while exploring an unconventional storytelling method.

The Unreliable Teleplay offers a potential option for creative expression, allowing stories to be retold and reimagined within the same world without the need for multiverses or time travel.

I'm not a big movies fan myself and have seen very little of these big and popular masterpieces.

But when I do watch movies I'm that guy who points out the obvious plot hole problems in the middle of watching :D

When a narrator is used to explain plot holes it often times feels very lazy way of doing things, I prefer when flashback scenes or some direct contact scenes are rather used for explanations.

But then again, I'm not a big fan of movies and watch them very rarely.

Oh, you're one of those. 😇