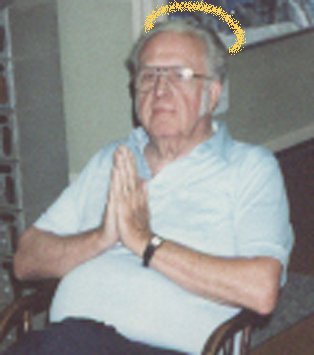

This is my dad’s 2006 Day Planner. Every single year, no matter what, he got a new one, put it in his back pocket when he got dressed for the day, and took it with him everywhere he went.

But 2006 wasn’t exactly an eventful year for Alex. He slept through almost all of it, and didn’t get out much. So you’d wonder what he could possibly have used this for. It turns out, every day is blank, except for the first one: December 26, 2005. And what he wrote there says a lot about who he was.

Last summer, I tried to capture who he was in a tribute I outlined and read from at a family reunion. Back then, I thought it sad that people don’t get to hear what’s said about them at their funerals. I intended to complete the outline later and send a finished version to him. But I crashed my computer, and lost it completely. And now I’m glad I did.

I remember it said Alex Sharp was a classic American, and went on to show how much his life paralleled 20th-century America. He was born in the early 1920s, right in the middle of the country, when it was thriving and growing like a child. On Sundays, he sat in little country churches, mostly unwillingly. But to his dying days, he liked many of the hymns he learned there. One a lot of us remember him liking is about climbing up Sunshine Mountain with your face to the sky. And one that he really, very much did not like about so-called Christian soldiers marching on to war. He was just a little guy, maybe five or six years old. But he understood those country sermons. And he not only understood them, he remembered what was said, thought about it and, we now know, sorted out a few important things. Like the difference between commanding authentic Christian character and proseletyzing circular Christian dogma. Like the value of choosing to conduct your life with honor, truth, compassion, kindness, sacrifice, courage, loyalty, and brotherhood. Like being willing to die for the benefit of other people. For people you don’t, and will never, know.

Last summer, I said something about how, in the 1930s, he tilled America’s earth. How the hard years of the Great Depression coincided with the hard years of his adolescence. How, as a strong young man in the 1940s, he fought with strong young America for good against evil. Last summer, I’d forgotten having once heard my dad talking about the G.I.s’ long wait just prior to D-Day. He and his shipmates were docked in England, and after some days passed without mail delivery, the troops started to complain. My dad said he, and/or one or some of his mates, went to have a word with the officer in charge of the matter. And they unexpectedly overheard him saying: “Why pass out mail? They’re not coming back.” When the officer turned around, one of the young sailors looked him in the eye and said, “So can we have our mail now?” Then, within a day or two, they set out on their mission knowing, or at least believing, they definitely would not survive what they were about to do. And they did it anyway. For people they didn’t, and would never, know. For the future. For us.

The bright beginning of that future was the 1950s—with all its peace, abundance, hope, prosperity, confidence, and pride—when it seemed like all of America was getting married and creating and raising children. Colorful fun was a way of life. Happiness and contentment weren’t the exception, despair and doubt weren’t the rule, and faith that most things in this world were just fine wasn’t peculiar.

America had built a shelter in which to express its true character. And so, it seems, had Alex. He was somebody people instinctively looked up to. We loved his intelligence, knowledge, and wit, carried by his magnificent voice. His discreet choice of words and skillful use of language. Sometimes strong language. The descriptive phrase “goddamn sons of bitches” never rolled off anybody’s tongue as effectively as it did his. He also came up with the most creative way I’ve ever heard of using but not using the too-common and undignified expletive that came to be favored by my generation. He turned “bleep” into a verb. (As in “the bleepin’ sons of bitches.”)

People loved to talk to him, and he liked, really, really liked, having a completely captive audience. He was made to be a trial lawyer. And a Coach. He coached my brothers and me, his Little Leaguers, wayward juveniles, probationers, clients in the public defender’s office, and the guys he studied law with in the 1960s. Among others.

All his life, he hated bullies and greed and hypocrisy. People who let others starve as they lazily extract masses of wealth from somebody else’s sweat disgusted and angered him. Usually, most of the time, by and large, as a rule, he lived and practiced fairness, generosity, kindness, and understanding. But not in order to placate the threat of a wrathful, punishing, mysterious force, or for fear of eternal damnation. He was kind to others because that’s what was in him. To empathize with those who struggle and suffer. With his work, his words, his vote, his time, his studies and awareness, he tried to lighten the load. Tried to align with people who would make the world a better place.

I said, last summer, that he, and America, were shaken on November 21, 1963, when evil men—inferior to people like Alex Sharp, lacking vision, compassion, and empathy—inverted the ground Americans stood on and caused the beginning of an upheaval that continues to this day. Change came barreling down on America like an iron ball from a cannon. And nobody was fully prepared for it. I think it led, among other things, to a sense of betrayal by the very youth for whom, really, the second world war had been fought. Youth who were later terrorized by a completely different kind of war, and a culture that was and still is changing by the day, and so were perhaps not at that time wise enough to understand the achievement of the foundations that had been laid before we got here.

Last summer’s tribute said something about how, in the 1970s, both Alex and America showed a few signs of fatigue, some cracks of despair. Things broke down. But never, for an instant, did Alex Sharp or America even think about giving up. With support from the person he so wisely chose to marry, Alex put his “hand upon the throttle, and his eye upon the rail.” He never lost sight of the vision and possibility of human life, and his own purpose here.

His life paralleled the 20th century in so many ways. He and my mother, her sisters and their husbands, the dear friends and nationwide peers who actively worked together and made decisions to create an era of peace, prosperity, and justice: you gave us literally everything you had, with vision, guts, and enormous love. We honor the sacrifices you made for us. The vision you had, and the promises you made, and kept.

So I’m glad I lost last summer’s outline. Because while it said Alex and his community represent the greatest era of the greatest country, it didn’t add: “So far.” Last summer’s version ended the story here. Which might have suggested the way of life, consciousness, vision, and great achievements, not just of a man, but an entire generation of men and women and their country, are not immortal, relentless, and invincible—even though they are.

Because what really happened is, sort of like a big bickering family, Alex, America, Americans, got on with the business of securing life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness by, for, and of all the people. Even if we didn’t exactly know how to go about it. Even if we’ve made a lot of mistakes along the way.

What Alex wouldn’t have wanted, what would be a travesty, is for the present and the future to have failed to preserve the vision, ideals, and character we witnessed in him and people like him, over the course of his lifetime. He wouldn’t want Americans to be sitting around some day looking back on better times. He wouldn’t want anybody saying ‘What ever happened to the people who fought the right fights, and died for the right causes?’

Another reason I’m glad I lost that old outline is it got me imagining having a conversation with him about one more paper I’m working on.

I’d call him up and say, “Dad? You got a minute?”

And after a little spat about whether or not I do or do not ever listen, he’d say, “Go ahead, shoot. What gives.”

“Dad, you’re going to have a completely captive audience, so I would love to know: is there anything you’d like to say at your funeral?”

Without hesitating, he’d say, “Yes.”

Then he’d whisper, very loudly, “Nobody’s waiting for you at any Pearly Gates. There’s no judgment day. There AIN’T NO SPOOKS.”

And he’d say, “Some of you aren’t going believe that, even with me not-standing right here telling you. But I went, and I looked, and I saw for myself, first-hand, that what I was telling you all that time was true: THERE AIN’T NO SPOOKS. And what you really won’t believe, what will really shock you, is there’s no hell either, and I’m not in it.

“So for the disbelievers among you, I quote the Book of Matthew: ‘Ye serpents, ye generation of vipers, how can ye escape the damnation of hell?’

“Here’s how: Forget judgment day. Forget the great by and by. It’s not about redemption and whosoever believeth-ing on Him having everlasting life. You don’t get everlasting life. But you do have some time right here, and right now. Play the game that way. As if what you do here and now matters.

“And I mean right now. Because you won’t be around to see what goes down at your funeral. Funerals aren’t for us dead folks. Don’t sweat it. The thing to do at a funeral is take a look at how much you all go around not copping to your love for each other. When you go to a funeral, take a look at how much people love people. Yes. That’s right. Take a look at how much you’re loved.”

He might quote the Book of Matthew again: “ ‘He that is greatest among you shall be your servant.’” And maybe he’d emphasize: “Your servant. Not your tyrant.”

And say, “Usually, most of the time, by and large, as a rule, it’s the not-famous, the not-rich who are the most powerful and most influential. They’re unquestionably the most important. Now, as always, for eternity, they anonymously build, they anonymously are, our great civilizations.”

“And while I’m at it: there’s no government or community out there, up there, or anywhere that isn’t right here. Your community isn’t greater than the sum of its parts. It’s no better than the best of you. So get out there and bully the bullies. Take on the goddamn sons of bitches who’ve eviscerated your systems of elected government, silenced your press, seized your property, and blinded you to your rights. Get off your bleepin’ asses and guard your laws, your freedoms, your institutions, your prosperity, your life, liberty, and happiness. Stand up to anybody who overtaxes, overworks, and overlooks you. Show anybody who poisons your water or earth a better way. Knock down anybody who tries to sell you your own life. Shout down anybody who tries to cloud your gentle truth with their violent dogma.”

And then maybe he’d take his 2006 Day Planner out of his back pocket, and turn to December 26, 2005, and read what he wrote there:

"If you’re Christian soldiers, march with pious feet.

Pound the drum of truth. Hear the wakened beat.

Don’t trust in false salvation. Don’t follow paths of fools.

And history may someday say, 'Now human freedom rules.' ”

Thinking he was finished, I’d say, “Um…”

And he’d shout, “Listen for Christ’s sake!”

“What you are up against now is not for the lazy. Not for the feint of heart. A lot of people will smear truth and justice for selfish reasons. A lot of people aren’t going to listen. A lot of people are going to get in your way. Don’t chicken out. Tackle this head on. Use everything you’ve got to live up to the challenge of asking, and honestly recognizing, what's possible and what's right. Hold forth for that. Never give up. Start over, again and again and again if you have to. Walk the path of justice, integrity, compassion, and truth, even if you have to go it alone. Even if you think you don’t know what to do.”

He might raise his hand and point at this sky, this dirt, this world and say: “This is the Promised Land. Here’s your heaven. Right here, right now. You be the angels.

“And you be the Yankees. And you be the Pirates. And you be the Red Sox.” And then he’d turn the country into one big baseball tournament, organize us all into our most effective positions, put himself in the third-base coach-box, point to America’s classic home-plate goals, and yell like he did at all his Little Leaguers, “Dig! Dig! Dig!”

And after we’ve had a lot of fun winning the game of freedom and justice, the last thing he’d try to say is “Give ‘em hell. I love you all.”

But he never would. He’d get too choked up.

very good post

Thank you!