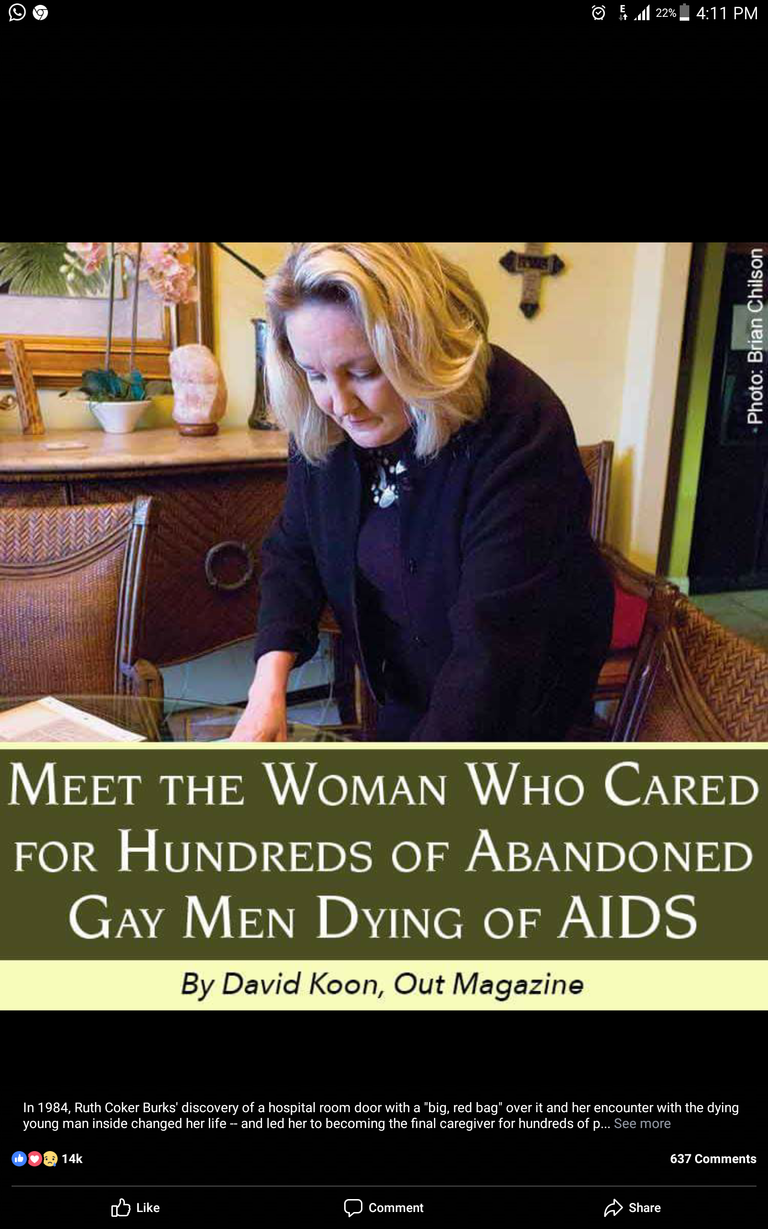

In 1984, Ruth Coker Burks' discovery of a hospital room door with a "big, red bag" over it and her encounter with the dying young man inside changed her life -- and led her to becoming the final caregiver for hundreds of people dying of AIDS, most of them young gay men who had been abandoned by their families. When Burks, then 25 years old, learned how many young men were being left to die alone and often were not even being claimed for burial, she recalls thinking, "Who knew there’d come a time when people didn’t want to bury their children?” Over the next ten years, Burks estimates that she helped care for over 1,000 people dying of AIDS and even dug the graves for 40 of them herself in her family's cemetery. While Ruth Coker Burks' work was nearly forgotten, it was brought to light this year when a crowdfunding campaign raised $75,000 to finally fulfill her dream of creating a memorial to those she buried at the cemetery. In recognition of today's World AIDS Day, we're sharing her inspiring story -- and the powerful and timeless lesson it teaches about the power of compassion to overcome fear and prejudice.

In 1984, Ruth Coker Burks' discovery of a hospital room door with a "big, red bag" over it and her encounter with the dying young man inside changed her life -- and led her to becoming the final caregiver for hundreds of people dying of AIDS, most of them young gay men who had been abandoned by their families. When Burks, then 25 years old, learned how many young men were being left to die alone and often were not even being claimed for burial, she recalls thinking, "Who knew there’d come a time when people didn’t want to bury their children?” Over the next ten years, Burks estimates that she helped care for over 1,000 people dying of AIDS and even dug the graves for 40 of them herself in her family's cemetery. While Ruth Coker Burks' work was nearly forgotten, it was brought to light this year when a crowdfunding campaign raised $75,000 to finally fulfill her dream of creating a memorial to those she buried at the cemetery. In recognition of today's World AIDS Day, we're sharing her inspiring story -- and the powerful and timeless lesson it teaches about the power of compassion to overcome fear and prejudice.

Burks was visiting a friend at University Hospital in Little Rock, Arkansas when she noticed a door with a big red bag over it. “I would watch the nurses draw straws to see who would go in and check on him,” she remembers. Burks, whose cousin was gay, knew enough about AIDS to guess who the patient inside the door was -- and fears about the disease didn’t stop her from sneaking into the room. Inside, she discovered a skeletal young man desperate to see his mother before he died. When she told the nurses, “They laughed. They said, ‘Honey, his mother’s not coming. He’s been here six weeks. Nobody’s coming.’” Burks convinced the nurses to give her his mother’s number and she tried reaching out one last time time, but it was obvious his mother had no intention of coming to see her “sinful” son who she considered already dead to her. So Burks returned to the room and took his hand. “I stayed with him for 13 hours while he took his last breaths on Earth.”

With his family refusing to claim his body, Burks decided to bury him herself in a local cemetery where her family owned hundreds of plots. “No one wanted him,” she says, “and I told him in those long 13 hours that I would take him to my beautiful little cemetery, where my daddy and grandparents were buried, and they would watch out over him.” The closest funeral home that agreed to cremate his body was 70 miles away and she paid for it out of her savings. A friend at a local pottery gave her a chipped cookie jar to use as an urn and she used a pair of posthole diggers to dig the hole. Over the next few years, when she became one of the go-to people in the conservative Southern state caring for people with AIDS, Burks buried more than 40 people in similar jars, most of them gay men who had been rejected by their families. “My daughter would go with me,” she recalls. “She had a little spade, and I had posthole diggers. I’d dig the hole, and she would help me. I’d bury them, and we’d have a do-it-yourself funeral. I couldn’t get a priest or a preacher. No one would even say anything over their graves.”

During this time, as the AIDS epidemic was devastating the gay community across the country, she began to get referrals from rural hospitals from across the state. "They just started coming,” she explains. “Word got out that there was this kind of wacko woman in Hot Springs who wasn’t afraid... I was their hospice. Their gay friends were their hospice. Their companions were their hospice.” Time and time again, Burks reached out to their parents but, out of the 1,000 people she cared for, she says that only a handful didn't reject their dying children. And, although she often saw the worst in people, she says she was also privileged to see people at their best as they cared for their friends and partners with dignity and grace: “I watched these men take care of their companions and watch them die... Now, you tell me that’s not love and devotion.” Burks also saw how the gay community supported one another and her efforts. “They would twirl up a drag show on Saturday night and here’d come the money. That’s how we’d buy medicine, that’s how we’d pay rent. If it hadn’t been for the drag queens, I don’t know what we would have done.”

By the mid-1990s, better treatment, education, and social acceptance made her efforts largely obsolete and Burks stopped caring for patients personally. Today, the work that she and others did on behalf of the many people who died during the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and early 1990s has been largely forgotten. However, thanks to a crowdfunding campaign which raised over $75,000, her dream to memorialize those she buried in Files Cemetery is coming true. A memorial is now in the early planning stages, one that Burks has long hoped will read, in part: "This is what happened. In 1984, it started. They just kept coming and coming. And they knew they would be remembered, loved and taken care of, and that someone would say a kind word over them .

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.facebook.com/Life-Gets-Better-Together-Salmon-Arm-216783335147758/