In my last post I observed that ethics codes for museum environments don't chart a clear path for cultural institutions to keep themselves above the fray of a market economy.

This guy knows all about having a code you live by.

Upon further reflection I realized that there is another gap in these ethical frameworks: none of them talk about fair compensation for labor.

The National Council on Public History (NCPH) Code of Ethics has several places where such a standard would fit.

Under "The Public Historian's Responsibility to Clients and Employers," for example, is "9. A public historian should not use the power of any office or professional relationship to seek or obtain a special advantage that is not in the public interest." This is an important rule, but should be accompanied by reassurance that compensation is fair.

Under "The Public Historian's Responsibility to the Profession and to Colleagues," is another opportunity:

- A public historian should contribute time and information to the professional development of students, interns, beginning professionals, and other colleagues.

That time and information should be accompanied by a living wage.

To NCPH's credit, they also have taken a stand for fair pay in the profession elsewhere on their website. This past December, they committed to not running advertisements for unpaid internships on the website job board. In justifying this decision, they made a compelling case for compensating interns:

Speaking generally, uncompensated internships are problematic for a host of reasons. At the most basic level, they make it harder for students and young professionals to gain experience in the field while maintaining a decent quality of life. They undeniably shape the demographics of the profession by favoring those who can afford to work for free and boxing out those who can’t. And they financially devalue the work we all do as public historians, psychologically undercutting our belief that public history is vital and important.

Gavroche gets why unpaid internships are bad news!

ASIDE: I suspect that the reason this same statement hasn't made it into the full ethics code yet is that many cultural organizations are still dependent on volunteer labor. While buy-in from a community is necessary for any cultural institution to function, relying on voluntarism perpetuates may of the same issues of demographic representation that NCPH took a stand against with unpaid internships.

Putting our own project under the microscope

In my last post, I reached a kind of a crux near the end. I took the easy way out and ended it with a question:

Of any of the statements, the NCPH code engages most with the market economy because many public historians work as consultants and contract workers rather than within institutions, yet it does not really engage with the inherent tensions between the public interest or trust and being for sale.

There are scholars who have teased apart some of these dynamics. In The Lowell Experiment, for instance, Cathy Stanton examined the role of National Park Service historians (DOI employees!) in essentially a capitalistic enterprise even as they sought to criticize historic abuses of capitalism. Perhaps this sort of critique does not fit the format or requirements of a code of ethics?

What would it mean to use one of these ethical frameworks to interrogate our own project, the Explore1918 experiment? The premise of this project is pretty simple:

- cultural institutions need varied funding sources

- cultural institutions have content that they want to share with audiences

- Steemit allows individuals and institutions to turn content into funding via the attention economy

So we (15 students and 1 professor, with @sndbox as consultants/cheerleaders) set out to raise money to grant to a cultural non-profit by curating content.

Let's step back and consider this plan in light of the NCPH Code of Ethics.

Right off the bat, it seems very in line with point #1:

Public historians should serve as advocates for the preservation, care, and accessibility of historical records and resources of all kinds, including intangible cultural resources.

Point #4 gets a little cloudier because the desired impact of the posts (beyond $$$ and proof of concept) were pretty vague:

Public historians should be fully cognizant of the purpose or purposes for which their work is intended, recognizing that research-based decisions and actions may have long-term consequences.

Zipping further ahead, one problem I've had is that I want to take a lot of time with these posts, which isn't efficient but is in line with the best practices of the field.

A public historian also should analyze each research problem within an appropriate body of scholarship drawn from all pertinent disciplines.

In short, I think this project passes the sniff test of the NCPH Code of Ethics, at least initially.

HOWEVER

This was intended as a proof of concept for cultural institutions to adopt the blockchain as a method of fundraising. Does the feasibility of this concept hold?

No.

Here is why: Social media is an important component of museum work today. The Museum of English Rural Life proved over the weekend that occasional virality can be the result of a solid social media strategy. Yet Steemit (and the blockchain more broadly) is not the place for this, at least not yet. Here are 3 reasons why:

There's no audience. It is not clear that our posts here on Steemit have any audience beyond our classmates, @sndbox, and Steemit bots. More importantly, our course of study emphasizes engagement with local rather than global communities, and very few Philadelphians are on Steemit.

Social Media positions are too often unpaid internships. Were any Philadelphia institutions to hop on the blockchain train, the chances are very high that they would do so with unpaid labor. The fact that our proof-of-concept experiment has been based on unpaid labor does nothing to disabuse them of this notion.

It's inefficient (at least in this cryptocurrency market). We have had 15 people posting about twice a week for twelve weeks and our savings currently amount to 2,701.257 STEEM. In a healthier market, that could be considerable, but currently that is projected to be worth about $6,500 even before one considers the loss incurred by cashing out. Each post takes me about an hour. I know that perhaps the case could be made that posting could be done more efficiently but I don't think it could be done both more quickly and also well.

15 authors x 24 posts each @ 1 hour per post = 360 hours

$6,500 divided by 360 hours gives an hourly earnings of about $18

I honestly don't know what the Return on Investment of most development work at cultural non-profits is, but I know that most of those folks earn more than $18 an hour. Frankly, any employment model that used Steemit as it exists in April of 2018 would, in my view, be an unethical one.

I just don't think it is worth it...currently.

I suspect that the response I will get from Steemians is this:

- The market will turn around! Crypto is the future! HODL!

- Steemit is itself a proof-of-concept and future blockchain apps will more seamlessly integrate the blockchain into social media.

These points are somewhat valid. While I don't really believe that STEEM will ever hit huge highs, it will probably get back near double digits at some point. And if the blockchain becomes part of mainstream life, of course museums should embrace it. However, it also feels like the blockchain hype is based on a fragile market to the extent that cashing out (to feed yourself) seems a little risky. That's not a healthy market.

IF cryptocurrency is every able to support a living wage, raise money, and provide a benefit as a content management tool (another point that the @sndbox guys have put forward) it could prove to be a boon for cultural organizations. But that potentiality would come with its own ethical quandaries and we are not there now.

TL;DR: Blockchain is not a panacea for cultural institutions.

Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's

No, the blockchain in not a panacea. I don't think anyone claimed it was.

Thanks for your review @tmaust, but I think your assumptions miss a major point. This course enabled its participants to engage with the subjects and materials of the semester on a blogging platform - something we could have done elsewhere and have earned nothing. By working on Steemit, we collectively earned funds that simply would not be available to us - to the sector - any other way.

Is this a model for nonprofits to embrace? What we proved, I think (and @remlaps seems to agree) is that more time (and patience) would be needed to build a viable, sustainable Steemit-based community.

What did we accomplish? We created something of interest and of value where there was nothing. Nobody was going to pay us to create the content we did. Nor should they have. Nor should we have accepted their funds if they had offered any.

Imagine a scaled up model of not 15, but 150 students posting their "homework" on Steemit and engaging with one another and building not $6,500, but $65,000. that wasn't there before. And imagine the opportunity to engage and create impact that would offer. Those students would have earned themselves a real stake in the sector.

No, the blockchain in not a panacea. But it is a new and different tool with real potential. In our own little way, even in a "down" market, I think we proved that.

very well said @phillyhistory!

I've always thought that this experiment was just that....a pioneering experiment and any earnings a boon, frosting on the cake so to speak.

I'd also challenge the idea that $18./hour isn't worthwhile....it's significant given the other gains occurring simultaneously especially given the short time invested here. Presumably, over time richer and enduring relationships would be built and more rewards gained. It takes real time to network and build relationships here on steemit just as it does out in the world. Was this component of each student's experience tracked? I'd be interested to know how much time each student gave to proactively reaching out to other steemians to develop relationships outside of @sndbox and classmates...

If this class or others were a regular feature on the platform they would gain a following. I found this class interesting to follow even if I didn't read every single post nor comment on all that I read. I believe that this format does offer the steemit community a glimpse into student's learning process within any given class and offers the students the valuable experience of a different paradigm. I can see this class at the very least as a useful catalyst to investigating blockchain tech which is undoubtedly one of the pathways of the present and future....and something each is paid for engaging with!

Thanks to you all for your comments! Thank you @remlaps and @hansikhouse for reading our posts. Thank you @kenfinkel for getting us in a position to have this conversation. I have a lot I want to respond to, because I think you all make some excellent points.

First I want to start off with where I'm coming from to this conversation. I've been looking around at how public history projects get funded and not loving what I see. I've been looking at how those same organizations pay the people on their front lines and not loving that easier. So when I say that Steemit is not a panacea, I do so because part of me was hoping it was.

You're all right that we did earn money, and that's great.

Many of you have essentially made the same point, that Steem is a young currency and Steemit is a young platform. Perhaps if given a longer timeframe, it could offer better returns. Perhaps there would be a community here that was interested in history. I hope that happens.

I think one of my fears here is that the pitch seems to be "money for nothing," when it actually requires a lot of labor. Since many of these organizations use unpaid or underpaid interns, it seems like a compounding concern.

At one point we talked in class about the possibility of Steemit tokens being added to other platforms. That assuages many of my concerns because it wouldn't require essentially copy-pasting (and setting off the plagiarism bots) or writing copy twice (which is really not easy).

Thank you folks for thoughtfully engaging with my work!

I've tried to read as many of your class's posts as I could. I think it's a fascinating experiment, and I enjoyed learning a little bit about PHL history. I've even resteemed a couple posts and/or shared them on facebook. So you have at least an audience of 1. ; -) I'm just more of a lurker than a commenter.

My rhetorical questions are, "Compared to what?" Are cultural institutions currently using wordpress or facebook? If so, what do they get paid to post there? I guess fundamentally the question is, "Is steemit a fundraising model or an employment model?"

I do agree with you that (for most people) it's probably not suitable as a sole source of reliable funding for full time employment - in the cultural sector or any other - but does that preclude its use for fundraising? Couldn't it just be part of someone's routine job duties at a cultural institution - in lieu of or in addition to the facebooking and blogging that they're already doing? I have to imagine that workers in the sector do lots of tasks that might not be easily justified purely by ROI or "financial return on time spent"?

Another factor that you might consider is the potential to recruit and grow your audience. Your class has been here for a couple months, and you'll be breaking up soon, but imagine an art museum with its donors who stay around month after month and year after year. Maybe the ROI calculation would be different for them. Wouldn't it be nice to be able to say to your donors,

How much would an institution bring in after a few years pursuing that sort of strategy - especially if their donors start to see some growth in the value of Steem's price?

Right. Thank you. This experiment would need more time to play out to prove itself.

Hi @tmaust. This is a very interesting aspect surrounding the use Steem, particularly in the cultural sector, so I wanted to jump in here and give my 2 cents. The ethics angle is a unique one and I'm glad you looked into it. On face value at certain times, it does seem like crypto does not seem a reliable/stable source of income/value. But there are a few crucial points that make what you and your colleagues have done something unprecedented.

First, and I'm starting with a more difficult one, earning crypto is far different than receiving a predetermined wage or payment. Volatility aside, it opens up the doors for donors (or in this case 'upvoters') to become personally invested in any effort you do. At this point, any Steemian that has read your class' posts are motivated to help you succeed since it will benefit their ultimate goal of raising market value as well. This is a very different relationship than some money-bags-McGee writing a fat check to a non-profit without any expectations. Crypto also adds a great deal of functionality that money cannot sustain, upvotes and curation rewards being the prime examples on the Steem blockchain.

Second, it has to be stated that non-profits do not operate with a sustainable business model. Unlike for-profit companies, employee work does not recoup or translate into direct profits for any institutions, thus making everyone that works in a museum reliant on debt and donation. I can understand the comparison of $18/hour with other hourly jobs, but from the perspective of an institution that is not efficiently monetizing that work, that amount of Steem is compensation they would otherwise never have access to.

This brings me to the point I cannot stress enough. Just like when engineers discovered ways of harvesting passive energy in solar, wind, and water that harvested a new resource more passively, tools like Steemit take the exact content that is being produced to no end in classrooms, studios, institutions, and so on and transforming that effort into an impactful resource/fund. @phillyhistory hit on this point as well that on a day-to-day basis, the vast majority of academic, social, and cultural work barely pass by more than a few pairs of eyes and are actually drains on existing resources. We're looking to flip that on its head. I don't know of any class in any subject in history that has accrued $5-10,000 with its homework.

And as a last little cherry on top, I'm guessing you did the hourly evaluations yesterday when the price of Steem was ~2 USD. As of now, it looks like the token is maintaining momentum at about 35% above that, shifting the ~18USD to ~24USD.

We at @sndbox will write some articles soon that elaborate on each of these points and again, thanks for bringing this topic up as it helps us make a stronger case for using crypto as well!

This just seems harsh.

I know, and I wish it were not the case. To clarify, I'm also including the vast amount of research, assignments, and thesis work that is usually only transferred between 2 or 3 pairs of hands. The vast amount of creative work (sketches, prototypes, napkin notes, even finished products), curatorial work, and social work do not make it farther than a dedicated few and a short lifespan.

For me, this all boils down to the fact that modern cultural production is for the most part incompatible with modern economy. Even the most 'successful' institutions in the world (let's take for example the Met or the MoMA just a subway ride away from me) cannot sustain themselves with their own cultural offerings (in the form of ticket sales or ticketed events). They are almost completely reliant on endowments and external support.

Again, what I think you and your classmates have done is monetize the previously unmonetizable and set a precedent for all types of cultural production, especially in the academic domain.

I think my fundamental discomfort is with that monetization. I think that modern cultural production should be incompatible with our current economy.

Give us bread, but give us roses.

I'm kind of shocked by the heat that this post is generating and I don't want to escalate the discussion into a more defensive place. But I believe that @tmaust has raised some necessary, if uncomfortable, questions about the issues of fair compensation and the ethical/practical sustainability of this project as it currently stands as a model for a more widespread funding strategy. He's laid out a reasonable argument and argues his point in reference to established professional ethics standards within the public history field.

Part of our job as public historians is to pose tough and thorny questions of our own work and that of our colleagues; evaluative self-reflection is a natural outcome of the advanced training in critical thinking for which we are going to graduate school to attain in the first place. The point of an experiment is to identify what works and what doesn't. The next iteration will look different, and the next after that further still. I don't see @tmaust disputing that anywhere.

I don't mean to come off as defensive. I do mean to challenge assumptions when they are (in my opinion) off target. Yes, it's important "to raise difficult questions about fair compensation and the ethical/practical sustainability of this project" but I disagree with @tmaust's assumption that the use of Steemit would necessarily fall to unpaid interns. (I'm all for banning unpaid internships as unethical and bad practice.) Burdening the use of Steemit with the practice of unpaid internships is not giving the former its due.

You are right that my assumption is just that: an assumption. A cultural institution with a well -developed social media presence could use Steemit and pay someone a living wage. I worry that they transitional period--the proof-of-concept--would rely on unpaid or underpaid content creators.

This is fantastic, thank you for teasing a lot of this apart! This post is especially valuable in the context of the most recent one. I agree with you on all fronts, particularly that this is currently (and thus, there is room for change in the future) not a viable option, particularly if we want to provide public history workers with a truly livable wage. Great work!

Awesome work, Ted. In my process of understanding blockchain I have really clung to the comparison to stocks. But....we wouldn't ask a cultural institution to invest their revenues in the stock market. Maybe that's an oversimplification. I don't think I have anything to add beyond what you've said, but I agree with you. It feels too risky at this point to be worth taking on.

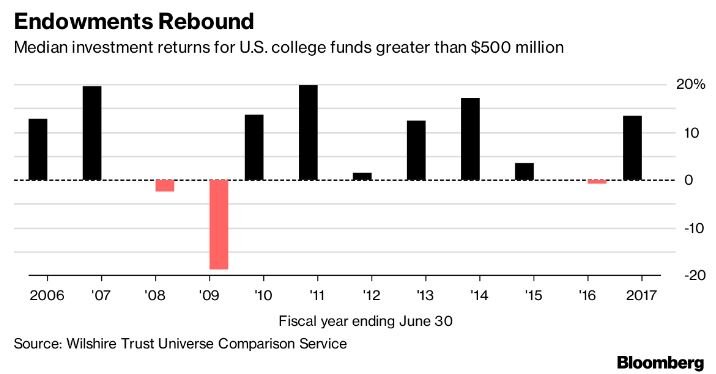

I might not be understanding you fully, but don't cultural institutions depend largely on the stock market for their endowments? And aren't they at the mercy of factors entirely out of their control? We can look at the impact of the recession a decade ago, for instance, when the geniuses at Harvard lost 22%. Take a look at this jarring chart and imagine yourself running a nonprofit in 2009 that depends on revenue from endowment. What was their response? HODL! Not unlike the cryptos of today. So how different is where we are from that?