In 2018, Amazon will announce the location for its second headquarters—an estimated $5 billion project expected to revolutionize the “winning” city’s infrastructure and economy. The tech giant recently narrowed their search down to twenty cities, including Philadelphia, and many have expressed considerable concern over the possibility of accelerated gentrification. A similar scenario unfolded in 1918, when Philadelphia became one of three cities to first welcome U.S. airmail service, and we can use this event as historical precedent to frame our conversation regarding the transformative effect industry has on local communities.

On May 15, 1918, residents in Northeast Philadelphia awoke to the sound of gasoline trucks, airplane engines, and cheering crowds as the city prepared for the inaugural flight of U.S. airmail services. Since Philadelphia served as the connection between New York City and Washington D.C., the quiet Bustleton community attracted national attention. Shortly before 9:00 a.m., Army Major Reuben H. Fleet took off from the Bustleton airfield and headed towards Washington D.C. where President Woodrow Wilson welcomed the arrival of the first airmail delivery. (1)

Later in the afternoon, “a great crowd of cheering spectators, which had assembled at the Bustleton flying field hours before he was due to arrive, gave a welcome to Lieutenant Torey Webb…” The Evening Public Ledger reported. “He piloted the first airplane of the postal service from New York to Philadelphia.” (2)

The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 16, 1918. (From Newspapers.com)

The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 16, 1918. (From Newspapers.com)

This event signaled a new age for aviation endeavors. As American cities observed the success of airmail delivery, not to mention the military’s new use of fighter pilots and a growing number of commercial airlines, many expanded their airport facilities and launched a drastic transformation of their urban landscapes. (3)

In 1929, the Aviation Committee of the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce published a report on the condition of the city’s airport infrastructure and warned, “if Philadelphia is to become the principal air transportation center of the east…[it] must immediately set about providing the one needed link in the chain—adequate air terminal facilities.” (4) City officials considered a number of landing fields to use as Philadelphia’s main airport (including the Bustleton landing field, then named William Penn Airport). The report suggested the mayor and City Council support the Hog Island Airport site for its access to the navy yards and room for expansion. The Delaware River in the south and Schuylkill River in the east, however, made any future expansion focus north—directly towards the Eastwick community—a rural neighborhood in the city’s southwest corner. (5)

In 1930, the city purchased the Hog Island site from the federal government and slowly transformed the area into the modern Philadelphia International Airport. The new airport facilities modernized Philadelphia’s aviation infrastructure, but it also displaced thousands of residents from Eastwick. Not only did the airport expand its physical footprint into the local neighborhood, but businesses developed restaurants, hotels, and other amenities to accommodate visiting passengers. The airport helped Philadelphia in terms of infrastructure development and economic growth, but it also had more personal consequences to the thousands of Philadelphians who once called Eastwick home.

Aerial image of Philadelphia International Airport looking north towards Eastwick, circa 1958. Courtesy of Philadelphia International Airport.

Aerial image of Philadelphia International Airport looking north towards Eastwick, circa 1958. Courtesy of Philadelphia International Airport.

Of course, this is not an argument against Philadelphia International Airport but a reminder to consider the personal impact of industrial development. When residents gathered near Bustleton airfield and witnessed Lt. Webb descending from the sky in 1918, many were optimistic about Philadelphia’s aviation potential. City officials invested in airport infrastructure because they saw an opportunity to expand the region's economic competitiveness. They sacrificed Eastwick’s unique identity in favor of economic growth and removed the rural community from Philadelphia’s map.

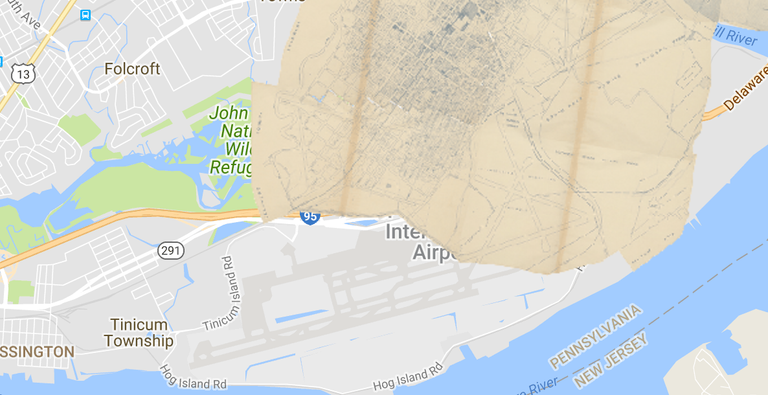

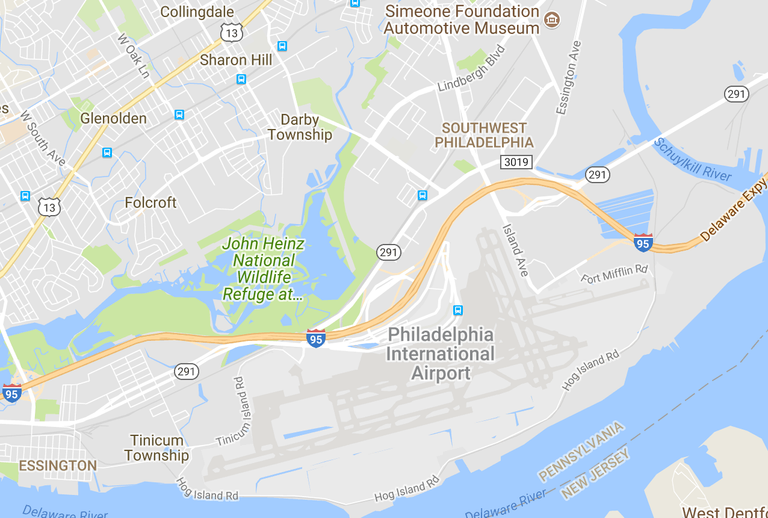

Modern map of Philadelphia International Airport with overlay of 1942 map of Eastwick neighborhood. 1942 map from Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network.

Modern map of Philadelphia International Airport with overlay of 1942 map of Eastwick neighborhood. 1942 map from Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network.

When Amazon announces the location of its second headquarters, the host city will receive national attention similar to Philadelphia in 1918. Many will optimistically look towards the future and embrace the anticipated changes, but others, similar to the Eastwick residents, will prepare to be forgotten. Their streets, homes, and personal memories will be erased from the cultural landscape of the city.

Resources:

(1) Dr. Henry Silcox, Remembering Northeast Philadelphia, (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2009).

(2) “Daily Aerial Mail Service Now a Fact,” The Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia, Pa), Wednesday, May 15, 1918.

(3) See Jaret R. Daly Bednarek, America’s Airports: Airfield Development, 1918-1947, (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2001).

(4)“All-Philadelphia Conference Municipal Airport Site…,” The Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce, 1929.

(5)See “1920s-1930s,” Philadelphia International Airport.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program, is exploring history and empowering education. Click here to learn more.

Great job using history to make an effective argument about why people are nervous about Amazon coming to Philly. Your conclusion was especially powerful.

Thanks, Joy!

Nice find! I wonder how this phase is interpreted in Eastwick histories.

Nice post! You do a great job making important parallels between this story and current events. Someone send this to Mayor Kenney!

I like the information on the first airmail and Philadelphia's importance in aviation. PHL still punches above its weight in terms of air traffic vs. population which is impressive considering the proximity of major airports.

Perhaps Bustleton might've turned out like Chicago Midway had the city continued to develop it in its inland location.