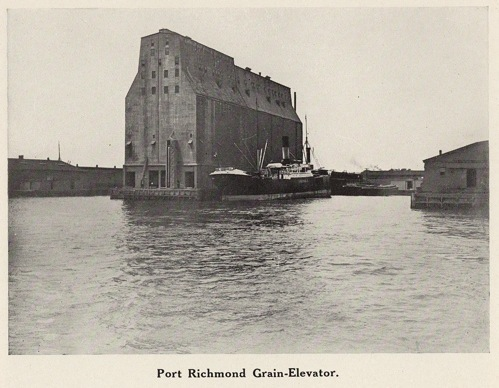

- Port Richmond Grain-Elevator, Philadelphia, PA, 1917. After his arrival in Philadelphia, Steffens worked as a ship's carpenter, building partitions aboard tramp ships which carried grain from this grain elevator to Europe. Photo from "William Steffens's Journey to the North," part of Goin' North: Tales from the First Great Migration to Philadelphia.

William Steffens was born and raised in Jacksonville, Florida, but he moved north to Philadelphia in 1918 along with hundreds of thousands of other African Americans who took part in the First Great Migration. Like so many others, Steffens heard promises of a better life; of a place with greater opportunities for gainful employment.

While many American soldiers were off fighting in World War I, industry in the northern United States found itself wanting for laborers. To meet this need, many, including Steffens, left their homes in the South for what they hoped would be a better future for themselves. African American came and found jobs as dockworkers, firefighters, janitors, and in Steffens’s case, ship carpenters. As a ship carpenter, Steffens was responsible for building partitions for the tramp ships in Port Richmond, along the Delaware River, that left Philadelphia to take grain and other foodstuffs to Allied forces during the war.

After the war, Steffens set up his own paper hanging business, starting out at first as a contractor. It was through his work as a contractor, however, that he quickly encountered the racism that existed within Philadelphia’s building trades. As he testified in his interview with Donna DeVore in 1984:

“'Don’t you join no union,’ [another worker] said, ‘because if you do, you’ll never get work,’ he said, ‘because if you join the union, you will have to agree to union terms, and declare that you’re going to follow out all the union terms and obligations, and that means that you wouldn’t be able to take a job, and work for less than union wages, and colored people couldn’t pay union wages. And white men wouldn’t pay you union wages, when they could get a white man to do the same job.’ He said, ‘And if you take that, you see, you would never get a job, because as soon as you took a job for a colored client, you would be regarded as a scab, because you couldn’t get union wages from them, because they were poor people, and they had homes, but they needed some work done, but they couldn’t pay union wages.’ And he said, ‘So you stay out of the union.’” – William Steffens, May 24, 1984”

- African American Porter at the Broad Street Station, Philadelphia, PA, Philadelphia Record, circa 1940. When Steffens began working as a contractor in Philadelphia he realized that, although he could sit side-by-side with White people, when he left the train, they would be off to their office jobs and they expected him in a service industry. Photo from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Despite the racial boundaries he had to maneuver in the building trades, his work as a contractor and paper hanger enabled Steffens to provide for his family. And although he was able to make a better life for himself in Philadelphia than he could have been back in Jacksonville, Florida, Steffen held no allusion about the atmosphere within which he lived. Growing up in Jacksonville, even at the age of five years old, he was aware of the violence perpetuated against Black men who White men perceived as having “stepped out of line” in one way or another. At the beginning of his interview with Donna DeVore in 1984, he recounted a story from his childhood in which he could smell that the Ku Klux Klan had burned a Black man alive at the state fair. He was further aware that after such horrific events, White people would take parts of the man’s remains home for their mantels.

The violence against African Americans that Steffens encountered in Florida was one of many reasons he knew he had to leave for the North. He never cowed to the systematic power and aggression White men wielded in Jacksonville, and by the time he left, some White men had begun labeling him as “uppity.” And although things were different and better in the North, he was still forced to endure the same denial of humanity he grew up with in Jacksonville. In his own words:

“So I felt then, that the opportunities that they told me would be available to me before I left the South, it wasn’t so. I found out to my consternation that the white man up North was perfectly satisfied to ride with you on the subway cars, or on the elevator trains, and sit by the side of you, because when he got up to go to where he had to go, he got up with his briefcase, and went to his office. But when you got up, you went to a mop and broom, because there was no office for you to go to up here. But in the South, when colored men rode in the back in the busses, and the trains, and the trolley cars, in the South, when they got up, they went to their occupations, which was brick-laying, cement-finishing, carpentering, and mechanical engineering, but they had to ride in the back of the busses…. So that is the difference. It’s the same, it was, I found out, it was the same thing, only just painted with different colors. It was that same degree of segregation, and denying, denial of privileges that we thought we were going to enjoy when we came North.” – William Steffens, May 24, 1984

Despite the challenges Steffens faced when he came North, he persevered and was able to make a life for himself and his family in Philadelphia. He was a remarkable and dedicated man. A man of dignity. His story is one of hundreds of thousands of other African American men and women who came North, perhaps to Philadelphia, looking to create a better life. What makes him so remarkable, to me anyway, is that he was one migrant who was not afraid to speak truth to the power of injustice that he saw. Not in Jacksonville, Florida, and not in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment is part of a graduate course at Temple University's Center for Public History and is exploring history and empowering education to endow meaning. To learn more click here.

Sources:

[1] Jacob Downs, “World War I,” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, (Rutgers University, 2014). http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/world-war-i/. (Accessed 1/23/18).

[2] Drew Blumenthal, Norah Jones, Dante Silicato, and Renee Williams, “The Heart of a Worker,” West Chester University, HIS 601/HON 451 Great Migration and Digital Storytelling (Spring 2016). http://theheartofaworker.weebly.com/diligence.html

[3] Derek Duquette, “William Steffens’s Journey to the North,” Goin’ North. https://goinnorth.org/exhibits/show/william-steffens/steffens-migration-north

[4] Donna Devore, Interview with William Steffens, April 23, 1984. https://goinnorth.org/william-steffens-interview-1

[5] Donna Devore, Interview with William Steffens, May 24, 1984. https://goinnorth.org/william-steffens-interview-2

[5] Goin’ North: Tales from the First Great Migration to Philadelphia. https://goinnorth.org/william-steffens-interview-1

This is so interesting and that photo is 🔥 🔥 🔥

Really enjoyed reading about the journey of William Steffens. Interesting that looking back in 1984, he evaluated the south and north to be "the same thing , only just painted with different colors." I'd like to hear more about that.

I could see a post on the backstory of the work in the 1980s done by Charles Hardy. What led him to research and conduct those many interviews? What enabled his work on those radio documentaries? Where else is 1918 documented similarly? How does audio history augment and enhance our understanding of the past?