In Numbers 33:6-7 we read:

And they departed from Succoth, and pitched in Etham, which is in the edge of the wilderness. And they removed from Etham, and turned again unto Pihahiroth, which is before Baalzephon: and they pitched before Migdol. (Numbers 33:6-7)

In the Book of Exodus, we find the same lack of detail:

And they took their journey from Succoth, and encamped in Etham, in the edge of the wilderness. And the Lord went before them by day in a pillar of a cloud, to lead them the way; and by night in a pillar of fire, to give them light; to go by day and night: He took not away the pillar of the cloud by day, nor the pillar of fire by night, from before the people. And the Lord spake unto Moses, saying, Speak unto the children of Israel, that they turn and encamp before Pihahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, over against Baalzephon: before it shall ye encamp by the sea. (Exodus 13:20-14:02)

Clearly Etham lay somewhere between Succoth and the three places called Pihahiroth, Baalzephon and Migdol, and both Numbers and Exodus seem to imply that the Israelites altered the direction of their flight after reaching Etham. If these early Stations of the Exodus represent the nightly encampments of the Israelites, then that constrains the position of Etham: it must have lain within a day’s march of Succoth and a day’s march of Pihahiroth. The only thing we are told about Etham itself, however, is that it lay on the edge of the wilderness. Later, in Numbers 33:08, we are told:

And they departed from before Pihahiroth, and passed through the midst of the sea into the wilderness, and went three days’ journey in the wilderness of Etham, and pitched in Marah. (Numbers:33:08)

In Exodus 15:22-23, this same episode reads:

So Moses brought Israel from the Red sea, and they went out into the wilderness of Shur; and they went three days in the wilderness, and found no water. And when they came to Marah, they could not drink of the waters of Marah, for they were bitter: therefore the name of it was called Marah. (Exodus 15:22-23)

Clearly, the Wilderness of Etham and the Wilderness of Shur were one and the same. That, at least, is something to go on.

Etham and Shur

In the Jewish Study Bible, Jeffrey H Tigay comments:

Etham, an unidentified place, perhaps at the eastern end of the Wadi Tumilat, where the wadi meets the wilderness, near Lake Timsah (see map, p. 130). (Berlin & Brettler 134)

Tigay also notes that:

Etham (= Shur in Exod. 15.22) (Berlin & Brettler 349).

We have already seen that the name of the first station, Rameses, is probably an anachronistic reference to the Hyksos city of Avaris, which no longer existed when the Scriptures were written down. It is possible that Shur, in a similar fashion, was a later name for Etham. So where was Shur?

In Volume 4 of the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, G R Conder writes:

Shur ... The name of a desert East of the Gulf of Suez. The word means a “wall,” and may probably refer to the mountain wall of the Tih plateau as visible from the shore plains. In Ge 16:7 Hagar at Kadesh (`Ain Qadis) (see Ge 16:14) is said to have been “in the way to Shur.” Abraham also lived “between Kadesh and Shur” (Ge 20:1). The position of Shur is defined (Ge 25:18) as being “opposite Egypt on the way to Assyria.” After crossing the Red Sea (Ex 15:4) the Hebrews entered the desert of Shur (Ex 15:22), which extended southward a distance of three days’ journey. It is again noticed (I Sa 15:7) as being opposite Egypt, and (I Sa 27:8) as near Egypt. There is thus no doubt of its situation, on the East of the Red Sea, and of the Bitter Lakes. (Conder 4:2782)

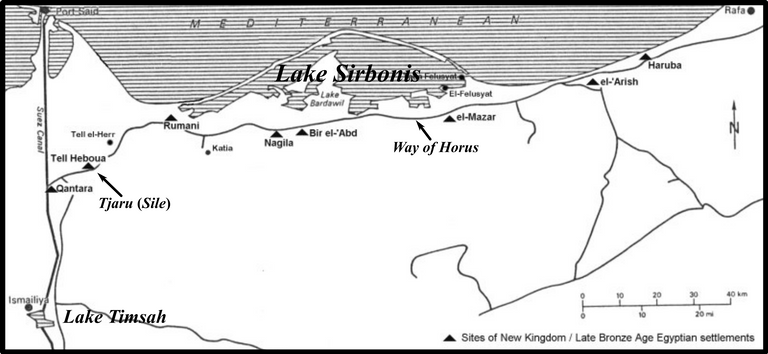

In a previous article in this series, I concluded that the way to Shur or way of Shur was just another name for the main coast road between Egypt and Palestine—the Way of Horus. This is supported by Genesis 25:18, in which Shur is on the way to Assyria. So Shur lay somewhere in the extreme northeast of Egypt. I believe this buttresses my suspicion that the Israelites initially followed the Way of Horus before turning south or southeast into Sinai.

In Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Shur is Number 7793, which is described thus in the accompanying Hebrew and Chaldee Dictionary:

7793. שׁוּר Shûwr, shoor; the same as 7791; Shur, a region of the desert:—Shur.

7791. שׁוּר shûwr, shoor; from 7788; a wall (as going about):—wall.

7788. שׁוּר shûwr, shoor; a prim[itive] root; prob[ably] to turn, i.e. travel about (as a harlot or merchant):—go, sing. (Strong 114)

Shur, therefore, signifies a wall in the sense of an obstacle that one must go round in order to reach one’s destination. The Tih Plateau rises in the northern part of Sinai. Looking south from the Way of Horus, it does resemble a wall on the southern horizon, but hardly one that fits this description.

In William Gesenius’s A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, the word Shur is defined thus:

pr[oper] n[oun] loc[ality] SW. of Palestine, on E. border of Egypt ... Oft[en] supposed to denote properly the ‘wall’ or line of fortresses, built by Egyptian kings across the isthmus of Suez; but dub[ious] (Brown, Robinson & Gesenius 1004)

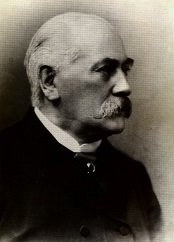

This idea derives from German Egyptologist Heinrich Karl Brugsch:

There lay in the direction of the north-east, on the western border of the so-called Lake Sirbonis, an important place for the defence of the frontier, called Anbu, that is ‘the wall,’ ‘the circumvallation.’ It is frequently mentioned by the ancients, not under its Egyptian appellation, but in the form of a translation. The Hebrews call it Shur, that is ‘the wall,’ and the Greeks ‘to Gerrhon,’ or ‘ta Gerrha,’ which means ‘the fences,’ or ‘enclosures.’ This remark will at a stroke remove all difficulties which have hitherto existed with reference to the origin of this word, which in spite of difference in sound nevertheless refers to one and the same place. (Brugsch 73-74)

Brugsch envisioned Anbu or Shur not as a line of fortresses but as a single strong point:

... there was, at the entrance of the road leading to Palestine, near the lake Sirbonis, a small fortification, to which, as early as the time of the nineteenth dynasty, the Egyptians gave the name of Anbu, that is, ‘the wall’ or ‘fence,’ a name, which the Greeks translated according to their custom, calling it Gerrhon ... The Hebrews likewise rendered the meaning of the Egyptian name by a translation, designating the military post on the Egyptian frontier by the name of Shur, which in their language signifies exactly the same as the word Anbu in Egyptian and the word Gerrhon in Greek, namely, ‘the wall.’ This Shur is the very place which is mentioned in Holy Scripture, not only as a frontier post between Egypt and Palestine, but also as the place whose name was given to the northern part of the desert on that side of Egypt. (Brugsch 214-215)

Brugsch was confident that Shur was situate at the (western) extremity of the Lake Sirbonis (Brugsch 233):

There is an ancient Egyptian site at this location: Rumani or Ramanah. There was a fortress here in Persian times. But Ramanah is about 80 km from Avaris as the crow flies, which is probably too great a distance to have been covered by the Israelites in just two days. A better candidate, in my opinion, would be Tjaru or Sile, which is now tentatively identified with Tell Hebua I. This lies about 50 km from Avaris, and overlooks the Way of Horus. It was from this fortress that the 18th-Dynasty Pharaoh Tuthmosis III set out on the first of his military campaigns into Canaan:

415. Year 22, fourth month of the second season (eighth month), on the twenty-fifth day, [his majesty was in] Tharu (Tᵓ-rw) on the first victorious expedition to [extend] the boundaries of Egypt with might— (Breasted 18th Dynasty §415)

Similarly, the Karnak reliefs of the campaigns of Seti I of the 19th-Dynasty depict him setting out from Tjaru. James Henry Breasted captions the first relief thus:

83. On leaving Tharu, his last station in Egypt, Seti strikes into the desert south of and merging into Palestine. (Breasted 19th Dynasty §83)

During the New Kingdom, Tjaru was clearly regarded as marking the Egyptian frontier on the Way of Horus. And if it was referred to as Anbu since the time of the 19th Dynasty, then there is every possibility that it was known to the Israelites by a different name at the time of the Exodus, a name they translated or transliterated as Etham.

Tjaru

In an earlier article in this series, we saw that when the Hyksos were defeated and expelled from Egypt, the first Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty Ahmose I first captured Tjaru before he besieged the Hyksos capital of Avaris. The evidence for this is found on the back of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (a mathematical work commissioned by a Hyksos Pharaoh ):

Regnal year 11, second month of shomu, Heliopolis was entered. First month of akhet, day 23, this southern prince broke into Tjaru. Day 25 – it was heard tell that Tjaru had been entered. Regnal year 11, first month of akhet, the birthday of Seth – a roar was emitted by the majesty of this god. The birthday of Isis, the sky poured rain. (Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology & the Ancient World: Brown University)

So Tjaru was a significant military post at the time of the Exodus—assuming the Exodus occurred at the time of the Expulsion of the Hyksos. Since the turn of the millennium, archaeologists have recognized the site of Tell Hebua I as the remains of Tjaru:

In 1998, the author [James Karl Hoffmeier] led a small team to reconnoiter in northern Sinai, east of the Suez Canal, between Qantara East and Pelusium to the northeast. We were interested in identifying a New Kingdom site that was part of Egypt’s eastern frontier defense system. Work had already been ongoing at Tell Hebua I since the mid-1980s by Mohamed Abd el-Maksoud. A massive fort was discovered there, and in 1999 a 13th-century B.C. statue was discovered with a dedication to “Horus Lord of Tjaru (Sile).” This discovery seems to confirm that Hebua was Egypt’s long sought east frontier capital and entry point from western Asia. The writer had thought for nearly a decade that Hebua was indeed ancient Tjaru/Sile, so this confirmation was most welcomed. (Hoffmeier 2015:177)

When Hoffmeier speaks of a “13th-century B.C. statue”, he is referring to an artifact of the New Kingdom, which is so dated in the mainstream chronology. In the Short Chronology, this artifact would be dated much later, and certainly long after the Exodus.

But if the third Station of the Exodus, Etham, refers to Tjaru, why does it bear the name Etham?

Etham

In Strong, Etham is Number 864:

864. אֵתׇם ’Êthâm, ay-thawmʹ; of Eg[yptian] der[ivation]; Etham, a place in the desert:—Etham. (Strong 18)

In Gesenius, the word is defined thus:

אֵתׇם pr[oper] n[oun] [locality] (perh[aps] = Egypt[ian] Chetam, cf. Ebers GS 521 f but Ὀθον, Ὀθων, cf Lag BN 54) Exodus 13:20 in Egypt, place on edge of desert, so Numbers 33:6-7 ... (Brown, Robinson & Gesenius 87)

In suggesting that the Biblical Etham may derive from the Egyptian Chetam, Gesenius is once again following Heinrich Brugsch:

Etham ... It is the place called Chetam, on various occasions, in the hieratic papyrus rolls, the meaning of which, ‘a shut-up place, a fortress,’ completely agrees with the Hebrew Etham. (Brugsch 69)

Brugsch does not explain how the Egyptian Chetam (or Khetam, as he spells it later in the same work) completely agrees with the Hebrew Etham. In the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, C R Conder takes him to task over this:

Brugsch [History of Egypt, Volume 2, p 389] would compare Etham with the Egyptian Khetam (“fort”), but the Hebrew word has no guttural. The word Khetam is not the name of a place (see Pierret, Vocabulaire hiéroglyphique 453), and more than one such “fort” seems to be noticed. (Conder 2:1012)

James K Hoffmeier is even more explicit:

The meaning of the word ’ēṯām is obscure, which makes determining the location problematic. It has been associated with the Egyptian ḫtm (fort), an attractive solution, but one that poses a serious linguistic problem that a number of scholars have recognized. A shift from Egyptian ḫ to Hebrew aleph is improbable since the Egyptian ḫ normally corresponds to Hebrew ḥ. If Etham is a writing for Egyptian ḫtm, one would have to admit an error in transmission or pronunciation ... (Hoffmeier 1996:182)

Hoffmeier also regards as anomalous the mere idea that one of the Stations of the Exodus could have been an Egyptian military fortress:

But ... surely the fleeing Hebrews would not purposefully camp near an Egyptian fort ... (Hoffmeier 1996:182)

Hoffmeier accepts the Biblical tradition that the Israelites were being pursued by the Egyptians. I, however, believe that this tradition is a confused memory of the pursuit of the Hyksos. The Israelites were simply the House of Israel or Jacob, an extended family of pastoralists who were not really of any concern to the Egyptians. The Egyptians had bigger fish to fry. There was a war of liberation to win against the Hyksos (ie Assyrians). So I do not think the Israelites would have avoided Tjaru if the main theatre of the war had shifted further east along the Way of Horus. As we saw in an earlier article, after the Hyksos escaped from Egypt they were pursued by the victorious Ahmose I to Sharuhen in southern Canaan.

Another possible etymology for Etham is briefly mentioned by Hoffmeier before he rejects it:

Alternatively, Manfred Görg has suggested that Etham is shortened writing for the Egyptian p(r)itm, that is, Pithom (Exodus 1:11), but with the initial element Pi omitted as in the case of (Pi)Raamses in the Pentateuch. (Hoffmeier 1996:182)

Like Rameses, Pithom was probably a late anachronistic name used by the Biblical scribes to describe a place that had not borne that name at the time of the Sojourn or the Exodus. Consensus is growing among Egyptologists that Pithom was originally located at Tell el-Retabeh in the Wadi Tumilat, but that it was moved 12 km east to Tell el-Maskhutah by Necho II (Hoffmeier 64), who reigned after the Exodus. There was, however, a Hyksos fortress at Tell el-Maskhutah at the time of the Exodus (Hoffmeier 67). I believe this is the place the Biblical scribes are referring to when they write of Pithom. But could this fortress have been the Etham of the Bible? The problem with this is that Etham is not the later anachronistic name used by the Biblical scribes but the original name. The modernized form was Shur, which points to a location further north where the Egyptian “Wall” or Anbu stood.

In Greek texts, such as the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible, Etham is rendered Ὀθον [Othon], Ὀθων [Othōn], and even Βουθαν [Bouthan] (Numbers 33:07), which is not unlike a corrupted Pithom. Nevertheless, it is difficult to draw any hard conclusions from these variant readings. Hoffmeier’s final verdict is one that I am compelled to share:

Unfortunately, with the knowledge presently available, the location and nature of this encampment, as well as the meaning of Etham, will have to remain uncertain. (Hoffmeier 1996:182)

But for the time being, however, I am going to identify Etham with Tjaru—at least, tentatively.

To be continued ...

References

- Adele Berlin & Marc Zvi Brettler (editors), _The Jewish Study Bible , Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1999)

- James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Volumes 1-5, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1906)

- Francis Brown, Edward Robinson, William Gesenius, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, Clarendon Press, Oxford (1906)

- Heinrich Karl Brugsch, The True Story of the Exodus of Israel, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Francis H Underwood, Lee and Shepard Publishers, Boston (1880)

- Heinrich Karl Brugsch, A History of Egypt under the Pharaohs, Volume 2, Second Edition, Translated and Edited from the German by Philip Smith, John Murray, London (1881)

- James K Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1996)

- James Karl Hoffmeier, Akhenaten and the Origins of Monotheism, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2015)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia, Volume 4, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- Paul Pierret, Vocabulaire Hiéroglyphique, F Vieweg, Paris (1875)

- James Strong, The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

- George Valsamis, Septuagint Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy: The Greek Old Testament, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2018)

Image Credits

- The Tih Plateau: © LightLeak, Fair Use

- The Ruins of Tjaru: © 2018 Biblical Archaeology Society, Fair Use

- Heinrich Karl Brugsch: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

- Lake Sirbonis and the Way of Horus: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use

Learning post dear. Very important post it was

Another great post dear. Keep it up