After entering the Wilderness of Sin, the Israelites next encamped at a place called Dophkah. This, the Ninth Station of the Exodus, is included in the list of forty-two stations in the Book of Numbers, but neither it nor the Tenth Station (Alush) is mentioned in the Book of Exodus:

And they took their journey out of the wilderness of Sin, and encamped in Dophkah. And they departed from Dophkah, and encamped in Alush. (Numbers 33:12-13)

In the parallel narrative in the Book of Exodus, the Israelites pass directly from the Eighth Station, the Wilderness of Sin, to the Eleventh Station, Rephidim:

And all the congregation of the children of Israel journeyed from the wilderness of Sin, after their journeys, according to the commandment of the Lord, and pitched in Rephidim: and there was no water for the people to drink. (Exodus 17:1)

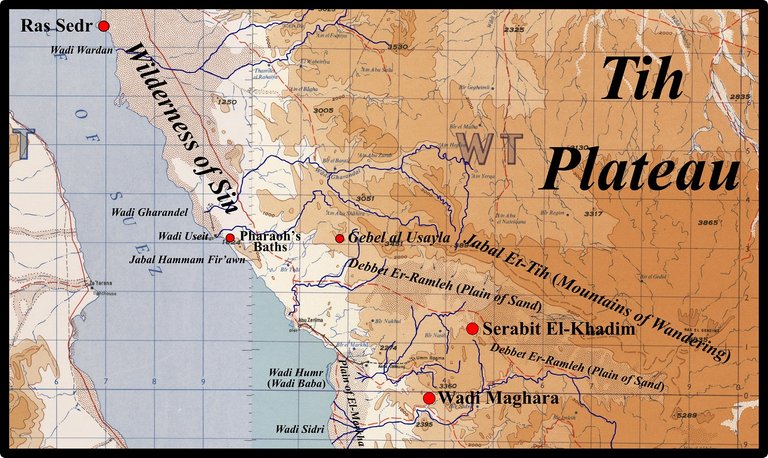

In the last few articles in this series, we came to the tentative conclusion that the Eighth Station of the Exodus, the Wilderness of Sin, referred to a coastal plain on the western side of the Sinai Peninsula, between Suez and Pharaoh’s Bath. We also saw that had the Israelites continued to follow the coast south of Pharaoh’s Bath, they would have been confronted with precipitous seacliffs at Jabal Hammam Fir’awn (Jebel Hammam Far’im, or the Mountain of Pharaoh’s Bath). They must have turned inland somewhere north of Jabal Hammam Fir’awn and ascended one of the many wadis (seasonal river valleys) that lead up to the Tih Plateau in the interior of the peninsula. This is also what we would expect if, as I have surmised, the Israelites were now making for Midian, the homeland of Moses’ father-in-law, Jethro.

But which wadi did they ascend? In the previous article we tentatively identified the Mountain of God where Moses receives the Tablets of the Ten Commandments, with Serabit el-Khadim, a copper and turquoise mining facility on the western edge of the Tih Plateau. With this as the Israelites’ immediate destination, what was the likeliest route they would have taken?

In our earlier study of Dophkah, we narrowed the Israelites’ choice to two wadis:

Wadi Gharandel: This valley reaches the Gulf of Suez about 10 km north of Jabal Hammam Fir’awn. It can be followed all the way up to the Tih Plateau, making it a plausible route taken by the Israelites. Its mouth lies about 40 km south of Ras Sedr. If the Israelites were covering 20-30 km per day, they would have had to camp overnight between the two—the Eighth Station of the Exodus, the Wilderness of Sin.

Wadi Useit: This is the last wadi before Jabal Hammam Fir’awn, but it is not particularly long and does not reach all the way to the summit of the Tih Plateau.

If Moses was familiar with this route—according to Exodus 3:1, he tended Jethro’s flocks in sight of the Mountain of God during his exile from Egypt after killing an overseer—he may have opted for the Wadi Gharandel. He would have known that it would have taken them all the way up to the summit of the Tih Plateau. On the other hand, if he was surprised by the impassable bluffs at Jabal Hammam Fir’awn, the Wadi Useit would have been the natural choice. The latter would also be the preferred choice if the Israelites were making for Serabit el-Khadim. The Wadi Useit may not be as long as the Wadi Gharandel, and it does not reach all the way to the summit of the Tih Plateau, but it does lead to the western edge of the Debbet Er-Ramleh, or Plain of Sand, a relatively flat expanse of desert which leads straight to Serabit el-Khadim.

If we accept our earlier identification of Ras Sedr with the Seventh Station (By the Yam Suph), and our earlier estimate of the Israelites’ rate of progress at 20-30 km per day, then the Eighth Station (Wilderness of Sin) would lie somewhere in the desert north of Wadi Gharandel and the Ninth Station (Dophkah) somewhere along the Wadi Useit. The start of the Wadi Useit is about 50 km south of Ras Sedr.

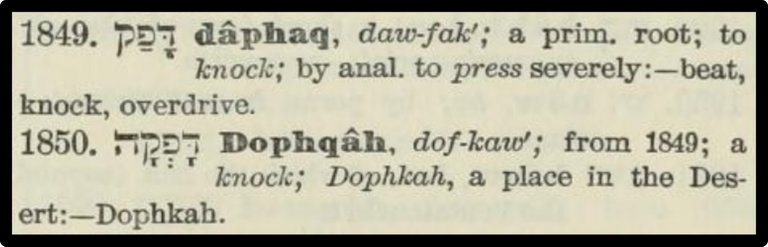

The etymology of the toponym Dophkah is unknown. As we have seen, some scholars have linked it to the Egyptian turquoise mines at Serabit el-Khadim, and while there is some similarity between the Biblical d-ph-k-h and the Egyptian word for turquoise, mfk’t (Budge 296, Pierret 193-194), only textual corruption can explain how the initial Egyptian m became the Biblical d.

James Strong derived the name from a primitive Hebrew root meaning to knock, which tells us nothing, but one of his alternative meanings, to overdrive, could be indicative of the fact that the Israelites were now negotiating a difficult uphill passage, requiring them to drive their beasts to the utmost of their natural capacity (Orr 3067).

Not everyone, however, thinks that the Israelites could have come this way. In the middle of the 19th century, the Scottish clergyman Robert Walter Stewart visited this region and drew the following conclusions from his own experiences:

We left Wadi Gherundel [Gharandel] at 8 o’clock, and following the course we had taken yesterday along the shore, entered Wadi Salmineh at 9 o’clock, then crossed over a narrow ridge of chalk, which separated it from Wadi Useit, and ascended the latter till we came to the wells, leaving the baggage camels in the former Wadi, because it is easier of ascent, and eventually merges in Wadi Useit. I was anxious to ascertain whether the Israelites, on the supposition of their having marched along the sea-shore, could have made the circuit of Ghebel Hummam [Jabal Hammam Fir’awn] by this Wadi, and the conclusion was soon arrived at, that by whatsoever path they travelled, it could not have been by this, because it is so narrow. During the two hours and a half which were occupied in ascending it from the shore to the wells, there is not a point between the perpendicular walls of this ravine where 20 men could walk abreast. It is as picturesque as it is magnificent. The rocks of pure white chalk laid in strata one above another, as regularly as stones on a building, rise from the bed of the torrent on either side to the height of from 50 to 300 feet [15–90 m]. The torrent bed is of the same chalky material. (Stewart 76-77)

In defence of the Wadi Useit, I would point out that I have already dispensed with the literal or Fundamentalist interpretation of the Scriptures, which has more than 603,550 (Numbers 1:46) persons taking part in the Exodus. If the House of Israel was merely the extended family, or clan, of Jacob (Israel), then the true number would have been considerably less. The narrow and ravined Wadi Useit could very well have accommodated them all.

On this point, it might be apposite to quote Lina Eckenstein, the scholar who first proposed Serabit el-Khadim as the Mountain of God:

Prof. Petrie proposed a different solution [Petrie & Currelly 211]. The word alaf in Hebrew signifies thousand, but it also signifies family or tent-settlement. If we read the census lists as preserved in Numbers taking the so-called thousands to signify families or tent-settlements, and the hundreds only as applying to the people, the census lists contain what appears to be a reasonable statement. Thus, the tribe of Judah, instead of numbering 74,600 persons, numbered 74 tent-settlements, containing 600 persons, i.e. about eight persons to each tent-settlement ; the tribe of Issachar, instead of numbering 54,400 persons, numbered 54 tent-settlements, containing 400 persons, and so forth. On this basis the Israelites, at the first census in Sinai, numbered 598 tent-settlements, with 5550 persons ; and at the second census, on the entry into Canaan, they numbered 596 tent-settlements with 5730 persons. The numbers 600,000 and so forth are attributable to a mistake of the scribe who added up the contingents of the census lists, reading the word alaf as thousand, instead of tent-settlement. (Eckenstein 73)

In Part 13 of this series, I estimated the number of Israelites at 6000, remarkably close to Petrie’s estimate, even though I was then unaware of his work.

It could also be argued that the difficult ascent which Stewart describes supports Strong’s interpretation of Dophkah as meaning to overdrive. It also supports the rabbinical interpretation of the name of the following station, Alush, as overcrowding (Orr 3067). Admittedly, this is all quite fanciful—possibly even farfetched—but I can do no better. It does at least have the virtue of fitting our tentative model quite well, even if things ought to be arranged the other way round.

To be continued ...

References

- E A Wallis Budge, An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, Volume 1, John Murray, London (1920)

- Lina Eckenstein, A History of Sinai, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London (1921)

- James K Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

- James Orr (General Editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 5, The Howard-Severance Company, Chicago (1915)

- William Flinders Petrie, Charles Trick Currelly, Researches in Sinai, E P Dutton and Company, New York (1906)

- Paul Pierret, Vocabulaire Hiéroglyphique, F Vieweg, Paris (1875)

- Robert Walter Stewart, The Tent and the Khan: A Journey to Sinai and Palestine, William Oliphant and Sons, Edinburgh (1857)

- James Strong, The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible, Eaton & Mains, New York (1890)

- Samuel Prideaux Tregelles, Wilhelm Gesenius, A Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures, Bagster, London (1857)

Image Credits

- R W Stewart: Copyright Unknown, Creative Commons License

- Western Sinai (Detail): University of Texas Libraries, Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Aqaba, Suez, D Survey, Great Britain War Office and Air Ministry (1960), Public Domain

- Looking South-East Across the Debbet Er-Ramleh: © 2014 Salma El Dardiry, Fair Use

Great post dear harlots.. hope you okay