In recent weeks, the EOS community has been engaged in a number of conversations around topics related to the inflation of the EOS token supply. We believe these to be important discussions, as inflation can have a direct impact on the security, distribution, and incentive structure of any given blockchain. When it comes to EOS in particular, we believe that the framing of the inflation debate has been overly simplistic. Inflation can be good, bad, or neutral, depending on where it flows and how it is used. The details of specific implementations are important to consider.

In this post, we’d like to outline concerns around EOS inflation that we believe haven’t been addressed in-depth. Our goal with this post is to demonstrate that there may be tangible benefits to EOS inflation that does not flow directly to validators (consensus participants), and tangible downsides to inflation that flows only to these participants. We hope that this contributes to the community conversation around these issues, and we look forward to hearing voter feedback and discussing these issues further.

Centralization Effects of Cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrencies are simple to analyze, mathematical structures of mini-economies with differing properties, often pre-defined and deterministic. Bitcoin, for example, will issue only 21 Million "units" before ceasing all inflation. This makes analysis quite unique -- we can analyze these closed-body economic systems exactly and with high fidelity, observing properties such as money velocity and distribution on a total scale as all information is public. In this post, we will seek to analyze the property of centralization over time.

There are many contributing factors in which a cryptocurrency system can have centralization forces – beyond the ones we think of commonly, such as accumulation of wealth. In Bitcoin, for example, we already observe miner centralization to select, large pools. In Proof of Stake (and the delegated variant) we see a similar phenomena; with a small, technically capable pool of potential consensus participants, the ability to decentralize is constrained by the number of capable parties. This debate continues to be on-going with Bitcoin. Proponents of "small blocks" argue that large blocks will forever burden newcomers with too much data, while proponents of "large blocks" argue that technology is advancing and the "forever burden" decreases with time and technological progress. In reality, the correct trade-off is likely somewhere in-between. Startup costs and long-term costs certainly can increase the centralization of the system, as newcomers are unable to afford to validate the system and the pool of potential consensus participants shrinks. Yet finding a correct balance between a technological cost that does not burden newcomers, and a system usable enough that it doesn't drive newcomers away in the first place, is a fine line to walk.

In Proof of Work systems, present rewards do not affect future rewards, as the ability to achieve a PoW is an external factor. This is what makes PoW systems "permissionless" – their consensus mechanism is not a closed-body system, and external input (in the form of electricity and 'work') is required. With DPoS systems, we have an interesting reward structure that is quite different compared to Proof of Work. In many DPoS systems the supply is not fixed but rather inflationary. This means that present rewards can actually affect future rewards. If we award those responsible for consensus with rewards that give more influence over consensus, then the system’s decentralization can be affected in the long-run.

Inflationary Rewards

To understand this problem, we need to take a step back and refresh our understanding of how exactly a property like inflation works in a closed-body system. As an example, suppose we have two people, Alice and Bob, each of whom have 100 units of currency. If Alice and Bob are both given 100 more units each, and each now has 200 units, has anything changed? In a closed body system, we have done absolutely nothing -- Alice had 100/200 units (50% of the currency) and now has 200/400 units (still 50% of the currency). Inflation that is uniform has no effect other than accounting of units. In the “percentage of currency supply” reference domain, inflation can only move the percentages. If instead we give 100 units to Alice but do not give Bob any more, then Bob still has his original 100, but Alice has 200. We've "inflated away" Bob's value— he has gone from owning 1/2 of the supply to owning just 1/3rd, and Alice has gone from owning 1/2 to owning 2/3rds.

Of course, the unit count (the number itself) also has psychological effects -- perhaps too complex to discuss simply here, and a topic for another time. The important takeaway here is that we must think about inflation as changing the percentage of ownership of the total supply. With inflation, for each win, there must be equal but opposite loss.

So how does this actually affect blockchain systems? In DPoS, control of consensus is determined by votes from the supply. In a simplistic form, those with the most supply of the currency will de-facto control consensus. And yet we reward consensus participants with rewards that inflate away those not in control of consensus. Imagine that Alice, Bob, and Charlie each own 1 unit of currency, for a total supply of 3. If they elect Alice and she inflates the supply by 1 and awards that to herself, she now has two votes (compared to 1 each for Bob and Charlie). Alice voting for herself is now impossible to overrule. When consensus is controlled in a closed-body way, eventually the present control of system snowballs into future increased control.

We can call this a form of "asymptotic convergence", whereby the supply collected by a specific entity, as a percentage of total outstanding supply, increases asymptotically in a closed-body system (i.e., it slowly gets closer and closer). While we have only used inflation as an example, this effect would also occur with fixed or variable fees, as well as with variable inflation, though the math would change slightly.

Asymptotic Consensus Convergence

When the supply of tokens is responsible for consensus, and the inflation is given to those presently in charge of consensus, then inflation can lead to centralization in the system over time. This is this asymptotic consensus convergence, whereby the control of consensus itself asymptotically converges.

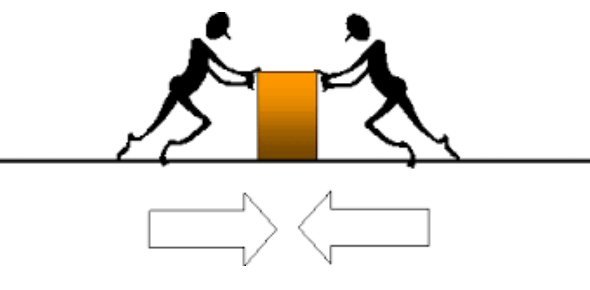

Of course, real-world systems are far more complex than the simple examples we have given. The consensus rewards are not always hoarded in full. To understand the effect, let’s make an analogy to physics. Suppose we have a box in the middle of a warehouse. If a constant force is applied to a box in a single direction, the box will move in that direction. If the force is opposed, the box will not move. In this analogy, the asymptotic consensus convergence is a fixed force applied in the direction of centralization towards the current elected set of consensus participants. This force can be opposed, but it would need to be voluntary. If the consensus participants always sell all their rewards (externalizing their value), the force is opposed in full.

However, if any of the consensus participants collect any of the reward, the box moves -- just a little bit. The more that do, the more the box moves. The force can be defined in terms of the reward:

As an example, this would yield a curve that looks like the following, if we suppose a reward (via inflation) of 1% per year:

https://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=(1.01%5Ey+-1)%2F(1.01%5Ey)+for+y%3D0+to+100In the above, we see the percentage of control in the system (that is to say, the control of the newly generated supply compared to the new total supply) go from zero to just under 10% in 10 years, and about 60% after 100 years. What this means is that, in that amount of time, the maximum rate the box could move in our analogy is at worst that amount (just by this force). We use the analogy of a force for a very important reason: opposing the force as an impulse only delays the immediate outcome, and does not prevent future effects -- in our example, consider opposing someone pushing a box constantly with a single kick: while it may delay them temporarily, it does not oppose their constant pushing.

While this doesn't sound like a problem today, the numbers should be concerning. In EOS, the top producer is presently elected by only about 12% of the supply. However, there is a multiplicative factor of 30 for votes in EOS: should a group of 30 agree, they can collectively amplify their votes (by vote trading) by that factor. In this case, a collective could achieve this dominance in, at worst, 5 months, entrenching themselves in a position only solvable by getting more of the supply to vote for a different group (and hoping that new group is more altruistic in their voluntary efforts of opposing the centralization force). This is not a ticking time-bomb with a sudden explosion; rather, this is a slow and painful drowning, struggling to breathe while the air slowly escapes.

In reality, the math gets complex quite fast when taking into account competing groups vying for a single dominating control of consensus. However, with some effort it can be proven that the largest collective (specifically, the set receiving the most votes from the current dominant set) eventually will win. This leads to a bit of a prisoner’s dilemma for those not within the largest collective — if you elect to join the dominating group, you may get 'rewarded.” If you refuse, and they are able to form with others, you will get nothing.

Counterbalancing the Centralization Force

If you're concerned about centralized participants forming an entrenched position due to inflation, then this argument has succeeded. Yet, we should consider not just how this problem exists, but how it could be solvable.

There are a few drastic measures that one could take. One example would be removing inflation to consensus participants altogether. This would indeed solve the problem, but it would remove the incentive for node operators to work for the network in the first place. As another attempt to solve the problem, a separation of token properties could be made: tokens that are voting capable (of fixed supply), and tokens that are utility tokens (of inflationary supply). In theory, the consensus participants are only paid out in minted utility tokens, and thus do not collect voting influence over time. However, this doesn’t actually work! We’ve just moved the problem to a different domain, so long as they can swap these tokens on the market.

Removing the inflation of voting rights completely is not the only solution, however. In fact, if a secondary source of inflation were added that went to a different source -- a force in an equal but opposite direction -- the centralization force could be balanced (or even result in net decentralization)!

In our equation above, the reward refers to the amount of the supply the consensus participants are receiving relative to the total supply. If we increase the total supply in another way that is specifically not going to the consensus participants, then their dominance over the system would not increase. Let’s go back to our previous example with Alice, Bob, and Charlie: Suppose each had 1 unit and Alice gained her extra unit just as before. But now, suppose Charlie also received 1 extra unit as well for a different reason -- Alice would have her extra vote checked and balanced. This would be in the form of additional inflation, for a different purpose. As with all inflation, there are winners and losers: in this case Bob is the loser by being "inflated away" -- but perhaps he was also the least engaged or otherwise not participating in the system itself.

Figuring out good reasons for a secondary, balancing force of inflation is, however, a hard problem. As we recall with the original problem of inflation -- in which, if we consider only the percentage of ownership rather than arbitrary unit counts -- inflation is simply a tool to move the percentage in the direction of one entity at the expense of another. Thus, we need to pick a winner (a new reward to some who are specifically not part of the consensus participants), and we need to pick new losers. You might think of an obvious solution -- we could just choose the winners to be everyone who is not a BP! But this would be an exact counterbalance and would be equivalent to not rewarding the BPs in the first place.

If you've been following the logic, then you know exactly where this is going next: worker proposals. Indeed, a clear solution to this problem is a secondary source of inflation that is guided by token holders into the hands of non-block producing entities that increase the value of the ecosystem. This could include funding to apps and services, grants and scholarships, and other expenses that could be made in the goal of improving the value of the network as a whole. It would be important to strongly encourage that block producers do not double dip into this fund, for if they do, the point becomes moot. With this secondary source of inflation, the centralization force would be countered, and could in fact become a force for decentralization. If the inflation to the community is greater than the inflation towards only the consensus participants, then, while the consensus participants may still be well paid for their efforts, their position is no longer the most attractive source of revenue.

There are many ways in which a worker proposal system could work, but consider a very simplistic approach: duplicate the block producer structure, but only assign pay by weight (vpay) and no pay for blocks (bpay). This secondary set of organizations would be elected separate from BPs, are not part of determining consensus, and gain their own inflation -- voted in place by the token holders. This would fit well for organizations that do not have technical or governance expertise, and could then spend all their time focusing on what they are good at; be it community outreach, marketing, scholarships, or other EOS business ventures. In fact, with this structure (or one like it), the consensus participants become further beholden to the community decisions, as more voting power is transferred into the hands of the community over time.

Summary

In this post, we've highlighted three important points that need to be considered when using inflation in a closed-body consensus system (like DPOS).

- Inflation itself is simply a tool to generate winners and losers in terms of ownership of total supply.

- If we award those responsible for consensus with rewards that give more influence over consensus, we end up entrenching those presently in power with more power.

- Thinking about solutions that prevent power consolidation is important, and one of the best ways to avoid it is with a counter balance -- ensuring that a single party or group is not the sole recipient of network rewards.

As the EOS community continues to debate the pros and cons of different configurations of EOS inflation, it’s important to remember the long-term and second-order effects that changes to this system can have. While direct decreases to the amount of inflation can seem like a positive outcome for token value, they should only be done in a way that ensures that the long-term health of the network remains sound. We believe that short term actions can create market movements in price, but long-term thinking drives true value creation. In order to achieve that, we must carefully consider how changes to critical parameters can affect the network’s centralization.

We look forward to engaging in further community debate around these topics in order to work together to diagnose and solve the hardest problems facing EOS.

Clarification Update

Since the first release of our post, there has been a lot of generated discussion and feedback, which we think is great! However, there are a few repeated comments on our post that often misunderstand either the terminology or the math. This brief update seeks to help clarify some of this.

First, there is some confusion on the use of the term "closed body", with many arguing that "EOS is not a closed body". To be fair, those with this position would be correct if we used the term "isolated system", however "closed body" has important distinctions. In physics, in an isolated system neither matter nor energy can escape or enter the system. However, in a closed body system, only matter is preserved (and extraneous energy is often only modeled). To make this analogous with our EOS system, the EOS tokens are like matter: tokens do not escape or enter the system from a non-observed point; we can track with perfect fidelity the location of tokens. However, the wealth of the system functions like energy, with external factors at play. As much as we all wish we could use simple levers to control wealth, the only tools we have are for controlling tokens. Thus, our investigation looks at the token distribution, not wealth or economic activity -- which are external variables. To further clarify why inflation is still a centralization force regardless of wealth, perhaps consider the following: even if no one sold tokens to consensus participants, they could still eventually control the supply. This is why closed-body analysis is still useful; it can be done independent of external factors.

From this misunderstanding, the argument typically drawn is that the consensus participants will sell some fraction of their tokens rather than keep them all. This position (despite being unrelated to the use of closed body analysis) does hold merit in regards to affecting the rate of centralization over time. Yet, as we have not seen anyone discuss the math yet, lets do just that.

The equation for this effect would look as follows:

.gif)

With rp being the individual participants' (of size P) reward, and ep being how much of that is expenses (and not withheld). As we can see, this confirms our previous statement that, if rp == ep ∀ p ∈ P, then the system is stable. However, when ep is less than rp, the effect remains: the asymptotic convergence approaches the ratio of (rp - ep)/rp rather than rp itself, like a damping factor. As an example, if all participants have a ratio of 1/2, the curve would instead look like this, with an asymptotic convergence towards 50% of the supply rather than 100%.

Finally, the breakdown into individual participants is important here: although the asymptotic convergence ratio is towards the sum of all participants, the participants could eventually greedily choose individual/new participants that increase control. For example, suppose half the participants had a ratio of 1/2, but the other half had a ratio of 1 (holding everything). This example has a convergence ratio of 3/4 in total, but interestingly, the set that held more can eventually replace the set that held less. This is because the set that withholds more of the inflation can eventually outvote the set that held less.

To summarize: consensus participants not withholding their rewards only delay the process, and further, hand control over to those willing to withhold more.

Finally, there are some questions about how initial distribution can affect the results. Once again, lets expand our formula to include initial distribution as a factor (don't worry, this change is simple):

.gif)

Here, we've introduced a constant term ip, a participants' individual initial ownership (for the purpose of the formula, this would be represented as fraction of initial total supply). As can be immediately noted, this summed factor can only end positive, and can only work to accelerate the timeline of asymptotic convergence. Indeed, this matches our intuition; taking into account initial distribution can only worsen the situation, it does not make things better.

Nice work!

Thanks for your hard work guys. Our proxy is delighted to have been a supporter from day one. Keep up the good work.

UnknownEssence had some interesting observations regarding your article. Have you consider his perspective? https://medium.com/@Unknown_Essence/a-proposal-for-dynamic-inflation-on-eos-128cbd5a0ace

It would be nice if a simplistic formula could be implemented. Perhaps it's too much to ask. However, by tying "value" to the USD one is necessarily using a peg that is doubly inflationary. We already know the published CPI, but it is not accurate as John Williams points out here.

One concern that could be addressed with a slight shift is the indefinite 1% (or 2%) inflation, as it increases in amount over time, regardless of the value of the token. Why not go with a static amount instead? This guarantees a diminishing inflation rate over time while providing a specific amount to work with. It also incentivizes all parties to work in ways that increase the value of the token over time.

As the ecosystem matures, the rate of inflation drops but the value of the pay should not, since demand will increase as well. And this avoids the cronyistic nature promoted by % rate inflation that guarantees an increase in pay year by year, regardless of value.

It's not perfect either. No amount of inflation will ever be perfect. But it provides a nice simple method of management that naturally ticks a lot of boxes.

In a theoretical sandbox world these ideas have merit, but when talking about a live blockchain there are additional factors that change the whole picture. Some of which are:

In regards to your second point - I think I would argue that while currently BPs are the best candidates for some of these funds - not all of the best candidates for these funds make good BPs. This happens in all DPoS, Steem and EOS included.

If a system like we're talking about was created, you'd end up seeing some of those who are currently BPs close out the block production side of their organization and move to the other side. It would be a smart move on their behalf. They are still rewarded for what they do, competing in the same way, are good at what they do, elected by the community, and give value (in the form of work) back into the system.

The difference is they are just no longer in control of consensus in the same way. The most critical role of a block producer is to actually produce blocks and keep the system running. Anything beyond that in which BPs choose to engage in, for the betterment of the DPOS chain in question, is "extra" in order to stand out in the competition.

A worker proposal system, whether this, or any other, provides an alternative to non-technical teams who don't need to be in charge of consensus.

I agree with you, in what you are saying, but it reinforces what I was saying - that if we prohibit BP's from entering the worker proposal market, we lose out on a lot of good stuff being made.

I would reduce the worker proposal funds to 1% and burn what has been gathered at the time when the worker proposals system goes live (so we don't have a pile of money waiting to be used, but would have to carefully consider every proposal)

... and I would not make any limitations on who could participate, because this creates a risk only in a sandbox environment where there are no expenses for producing blocks (or employing people to write code/host events/promote/etc).

I see the point - but I don't think there would be anything stopping them from still making good stuff and competing in the same ways they are now. When BPs have either excess time or funding, I'd like to think it's their obligation to then figure out the best ways to reinvest that back into the ecosystem. But when a situation arises, block producers need to rise up to the challenge, dropping their own projects, to make sure the network remains operational.

Here on Steem, despite my current personal status as a producer, I still perform this function. The "value-add" of my time/work has dwindled due to a lack in the aforementioned time/funding, but I still fill my primary role here. Steem could likely also benefit from the same setup, since arguably some elected witnesses aren't interested and/or technical enough to engage - it's just not as critical since the majority of inflation goes to those not in control of consensus.

EOS on the other hand, technically has all inflation going to Block Producers. Something has to offset it.

Just as an example, under this proposed system within EOS - Greymass would continue to still be a block producer first and foremost, but second to that we'd continue to offer our infrastructure support, research, end-user application development, and all the other initiatives we choose to take on in addition to our primary responsibility. The time/funding currently exists for us to do that in addition to what we're fundamentally responsible for.

If we didn't want to focus on block production or governance, and instead say we wanted to build a for-profit dapp company, we'd just switch to becoming an elected "worker", rather than a block producer. It's the same elected structure and branding initiatives, we'd just no longer be in charge of consensus.

This creates that duality needed to offset the inflation flowing already to block producers.

In the end, I really don't think we'd lose out on anything. If anything, we'd gain something, since there would be an entirely new set of elected organizations theoretically providing new value into the system. For existing block producers - it provides a choice to them on whether they want to focus on their product or on the network itself.

I'm actually working on a post really digging into this topic right now - so I definitely appreciate the conversation. It's helping provide a great perspective and things we may have not talked about internally.

Hi, Jesta, tks for analysis.

we understand that inflation is a way to pay BPs as they have spend their resources like fiat and time, etc for running the network. Their earned EOS will be used. Thus the current situation is not same as your example as Alice earn without doing anything.

EOS can be centralized if you are rich enough to buy a certain amount of EOS or like B1 since EOS is not one vote one person democratic system.

BPs can buy votes either off the line or on the line via many execuses like game rewards. The problem is still here.

A very basic principle that we can understand and should be promoted is that who contribute to the EOS system who will be rewarded by the community. I believe the main problem is that in many cases it is difficult to quantify how much to reward, who decide as we lack an objective measures. Unlike BPs rewards, it is simple and can be well defined. Dapps developers can be rewarded by tokens selling and in future capital market. Voting may not be possible all the time as community members are too busy maybe.

In addition, as one of the community members we are expecting BPs not only just doing a good job in blocks production but also responsible for marketing and promotion of EOS and others functions like operating a company. We will target to vote for an all round BPs.

One point is now we lack voters rewards. Voters stake and spend time for electing suitable BPs. The effort has to been rewarded. This rewarding from system is not difficult to quantity too.

As a conclusion, it is agreed that community members need to understand how inflation model can change the degree of centralization of the system in middle and long term. Rewards via inflation to different contributors parties to the system should be promoted from my point of view. Then the system will be more fair and decentralized further. By the way, we start to vote Greymass for almost 10 months. We hope that you can keep going and raise out the weakness of EOS in order to make EOS stronger.

Most of the analysis was actually @anyx, but I've been jumping in and responding to comments on and off :)

To give some point by point answers:

100% - we had hoped that our efforts in writing this thought piece would help get others thinking about the bigger picture happening within EOS. With comments like yours, I think we've succeeded to some degree!

We really do appreciate the votes, especially all along the way during this 10 month journey. So thank you, both for your thoughts and kind words.

Hi, Jesta. tks for reply. You have pointed out that some BPs have separate financial support which is quite true.

I am in your telegram group. Keep in touch.

I have followed EOS from ICO but join Steem almost the same time frame. Just feeling that the communication and collaboration between BPs and community are tighter in EOS but not Steem. Is it true? How do new community get in touch with witnesses of Steem? please advice.

Here's a small rebuttal article:

https://trybe.one/is-bp-pay-making-eos-centralized/

I just resteemed your post!

Why? @eosbpnews aggregates updates of active EOS BPs and conveniently serves them in one place!

This service is provided by @eosoceania. If you think we are doing useful work, consider supporting us with a vote :)

For any inquiries/issues please reach out on Telegram or Discord.

Juste great words ! Love that !

i am agree completely agree please make a proposal in EOS proposals and referendums !

they will be BPS the goberments with totally power in few years if we dont take hand s in work now

You still have a mathematical error in your calculations. You need to divide the 1% inflation between 70-90 BP's getting paid. Let us say that the top 30 get 70% of the 1% in a year, that is 0.7% divided between all of them. If all of them collude to only vote for each-other and save all their rewards, you still end up with 0.7% of the votes against the current 10-12% all of the top 21 have.

I would say dpos inflation is more similar to PoW than you are describing - in where the input is the labor, electricity, infra costs - but only elected BP's can do the mining for obvious reasons (excellent speed and reliability). So we end with the token-holders/developers having to buy 70 to 100% of block rewards and offsetting the inflation benefits BP's are gaining.

This makes EOS not really a closed system, since there is an offsetting loop required for it to run - the market where BP's can sell their tokens for whichever currency they use to pay their expenses and developers/investors buying these tokens to gain resources on the network.

The inflation is the sum of all rewards, by definition. I refer to this as "rewards" in the formula. Since accounts are effectively cost-less, it the count is irrelevant as a single entity could have many.

Its really, really, REALLY not.

In POW, consensus is NOT closed-body. Even if no tokens are exchanged in a POW chain, the ownership of consensus can change drastically.

One important phrase is "award those responsible for consensus with rewards that give more influence over consensus". This is really key to understanding the difference.

EOS is not an isolated system. I suggest reading the updated section to understand the difference.

This is in the formula, as ep. It just delays the effect, as mentioned.

First, the idea, that the ability to have multiple accounts, therefore we treat all BP's as one account, is far fetched and ignores the reality of the situation, where tens of teams are working their butts off to provide the community with a working blockchain/tools and support. (including Greymass)

Second, you are missing the point of EOS. If it was a "store of value" type of digital currency blockchain like some of the PoW are, the risks of centralization would be more pronounced, since no one would need to buy the tokens generated by inflation. In a resource and utility sharing chain on the other hand developers and users need the inflated resources or else they can not use enough resources. This might drive the price up, but it also pressures BP to sell their pay, which is offsetting the effects of the pull of power towards BP's.

All in all, I can see this gaining an equilibrium, where market forces will work to keep the balance. Yes currently it should be moving towards BP's gaining more of a foothold, but only by less than 0.5% a year (considering their expenses). At the same time developers and users are learning to use EOS, which drives up their voting activity.

In 5 years I would like to see well funded BP's, with excellent teams promoting and running EOS and also having a small stake in it to "make them loyal to EOS and keep them from creating their own chain". So I see this 2-3% of the total supply as the golden handcuffs in other corporate environments. Yes it also has effects on consensus, but they are marginal. By that time I see 20-30% voting activity, so they would have a 10% effect on consensus.

This by itself is not a bad thing since BP's are also stakeholders and should have a say in deciding the future of the chain. Will they refrain from voting for themselves when they see that another team could do more good than them? Probably no! Will they vote for another 29 BP's doing harm to their investment when they see that voting for better ones would increase the value of their investment? Probably no!

So I see this all as a non-issue that does not need tweaking or offsetting, since there are already forces that are doing that: developers/users, expenses and common economic sense. This does not mean, that I do not want a development fund for EOS - it just means we should keep the talk about that separate and not try to fix something that does not need fixing.