I go to the University of California at Berkeley, a college located in the northeastern region of the Bay Area, less than an hour away from the venerated Silicon Valley and a 30-minute Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) ride away from San Francisco. Up until my senior year of high school (I attended a conservative high school an additional 30 minutes east of Berkeley), my pipe dream was to study business, become a lawyer, and then enter politics.

At Cal, my dreams aren’t sexy. I am in my final year in the undergraduate program at the UC Berkeley Haas School of Business. I am also pursuing my degree within the Charles and Louise Travers Department of Political Science. However, despite politics being at the forefront of all major developments from science to technology to wealth inequality in our increasingly globalized world, my business school has become increasingly disconnected from these realities. I don’t say it because I think I am better, I say it because I think we can be better.

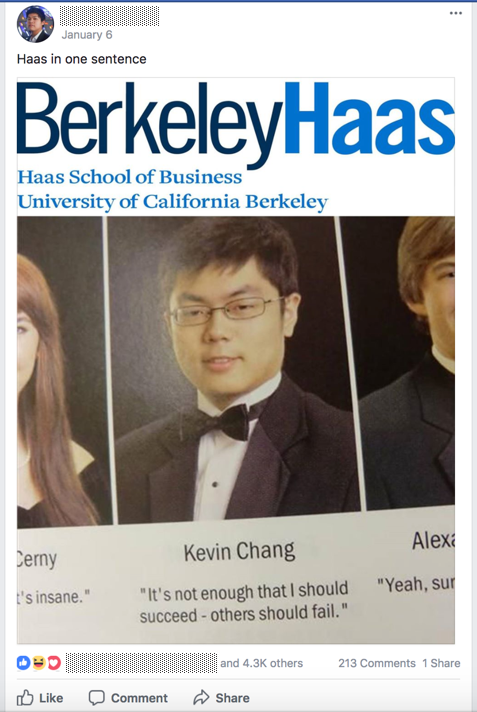

The undergraduate program is only two years, and involves a rigorous application process that takes place in a student’s sophomore year. The acceptance rate for the program is 14.21%, which only motivates students further. This motivation manifests itself in intense competition and pressure, which contributes further to Cal’s already cutthroat educational environment. “Pre-Haas” students are often caricatured as having a “snake-like mentality”, the subject of many memes on the campus’ unofficial, ubiquitous student-curated memes Facebook group.

Get it?

Still, I entered Haas with the hope that the small class sizes and renowned professors would inspired my new class of 200 or so students to be more than this.

My first year, I took a business communications course. At one point, we were asked to give an impromptu 3 minute speech on any topic we were interested in at the moment. I, being one of the first to speak, talked about the humanitarian crisis in South Sudan, because why not? I had just come from my class about civil war and international intervention.

As I spoke, I felt incredulous faces turn towards me. I wasn’t talking about a hot new stock or cool tech startup. It all felt very strange.

Then, finally, our class project at the end of the semester. Half of our class’ ideas (including my own) consisted of mobile applications. Mine utilized the Google Maps API to aggregate location data and tell users how long the wait would be at cafes, gyms, and other busy locations. Because that’s the next big technological advancement we needed in the world.

This push towards Silicon Valley affects everyone. This semester, construction finally finished on a new building at Haas, Connie & Kevin Chou Hall. Kevin Chou is an alumnus of Haas and the founder and CEO of the mobile gaming company, Kabam. He, along with his wife, Dr. Connie Chou, donated $25 million to the business school (along with purchasing $18 million to be given the naming rights of the school’s football stadium), in 2017. They are both 36 years old.

Construction plans for the new Chou Hall, connected to the Haas School of Business

I think the environment that the Haas School of Business fosters can be best summarized through a course I am taking with venture capitalist and lecturer at Cal, Rob Chandra. The course is entitled Alternative Investing: An Introduction to Venture Capital, Private Equity and Hedge Funds. It only meets once a week for two hours, yet nearly every Haas student enrolls to get into the heavily waitlisted class. Rob Chandra is a lifelong investor, having been an angel investor in companies like Alibaba, Dropbox, Twitter, and Uber. He now serves as President & CEO of his own venture capital firm, Avid Park Capital.

Every week, our class reviews a new startup, understanding the paths the founders and their investors took to make what is often a large tech company a billion-dollar brand. The whole class, many without any technical background, is eager to sink their teeth into a juicy new startup idea. We look at the market and how we believe it is evolving. How we can solve “the world’s problems”. But when you are looking at an app that allows users to compete in charade-like drawing competitions against their friends, or an apparel company that almost exclusively appeals to the “yoga mom market”, how much of the world’s problems are you actually solving? I entertain the possibility that the “world” we understand in the class extends very little beyond the confines of the Bay Area I have grown up in.

Of course, not everyone is interested in pure tech. If you ask any other student who doesn’t want to do “business operations” or “marketing” at a tech company, there is (according to my arbitrary, biased calculations) a 98% chance they’re pursuing a career in consulting or investment banking. Therefore, Chandra’s class helps them understand what a hedge fund is, because who the heck even really knows what that is besides that one reason why George Soros is famous?

We’ll have speakers too, which attempts to make it all real. Of course, the hedge fund manager who spoke talked about his most recent investment in the debt of Argentina, a poverty-stricken nation in the midst of economic restructuring by a corrupt government. I’m not sure my class even blinked.

If I said I hadn’t considered many times changing career paths because I have very few classmates to talk to about my own ambitions with, I’d be lying. I don’t believe there is anything inherently wrong with wanting to understand how our world is being changed by technology, and to take an active role in it. I don’t think Chandra himself actively condones a one-track mindset, and I admire his efforts to educate students at Haas because not only is he an excellent lecturer, but truly cares about students’ learning.

However, I think that it must be emphasized in our tech-minded education system that the world is so much bigger than Silicon Valley. I myself am still fighting to break out of this bubble I have lived my entire life in. We must challenge ourselves to read news, actively talk about, and apply our brilliant minds to the deep-rooted societal issues we face across the globe, whether it be humanitarian crises in Africa or understanding the implications of investments we make in third-world countries. And, we must do this in a collaborative way. Otherwise, we end up like Tom Perkins, founder of one of the world’s top VCs, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, who wrote to WSJ in 2014 comparing criticism of Bay Area elite to the Nazi genocide of Europe’s Jewish population. “I would call attention to the parallels of Nazi Germany to its war on its “one percent,” namely its Jews, to the progressive war on the American one percent, namely the “rich,” Perkins wrote.

We’re better than that.

[Originally posted on Medium.com] (http://medium.com/@michaelagines)

You got a 2.39% upvote from @postpromoter courtesy of @maxg!

@originalworks

The @OriginalWorks bot has determined this post by @michaelaerica to be original material and upvoted it!

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @originalworks or !originalworks in your message!