$100,000. That is the cost that a collective of my Dad, the government, richer students, and I had to pay for me to go to college. Between classes, room, the mandatory meal plan, and then books, $100,000 exchanged hands so that I could, four years later, be given a piece of paper that said I had received a Bachelor of Arts.

And while I was in school, not thinking at all about what $100,000 actually meant, I had a blast. I took biology classes that were more interesting than I gave them credit for, I failed a couple of those classes, and then switched to a major that made sense for me in my senior year. I became close with a group that are absolutely incredible that I still view as part of my inner tribe today.

But then reality hit after I graduated. For six months, I had a grace period from responsibility, which sounds like a great thing. Unfortunately, a life without responsibility costs money. After those six months, signed in to my Sallie Mae account. $185. And the Great Lakes account. $175. And the ACS account. $150. Every month, I needed to send money to those three companies.

It was during that time that I started to think about what I had gained from my education and my understanding of the situation evolved. I could tell you when the Magna Carta was signed and its significance, the evolution of political thought throughout the years, and each individual event that both led to the rise of Nazi Germany and what easily corrected mistakes could have led to a German victory during World War II.

Yet, none of those facts were going to help me with my new job as a SEO analyst. And then none of those facts or events were going to help me with my next job as a business analyst, responsible for both cutting costs, increasing revenue, and launching new products.

One thing was severely lacking in my education …

It’s Not About What the Dots Are, But How They Connect

There’s a quote found in the book, Stop Stealing Dreams, by Seth Godin, that really struck a chord with me as I continued pondering the net gain from my education:

The industrial model of school is organized around exposing students to ever increasing amounts of stuff and then testing them on it. Collecting dots. Almost none of it is spent in teaching them the skills necessary to connect dots.

Said another way … From pre-K through college, our lives are spent being given facts, information, and rules that are meant to be followed: dots. The bigger our bag of dots, the better we are at something. Yet, when you ask someone how they can take all of these dots and do something, that’s when things become a bit more foggy.

The problem I find is that teaching someone how the dots connect is not an inherently easy task because it goes against what we, as a society, value most:

- Trophies

- Money

- Grades

- Awards

- Diploma

In society, what is most valued are things that are quantifiable. You have won a lot of trophies, so you must be a great athlete. You have a lot of money, so you must be a great business man. You have high grades, so you must be smart. You receive awards, so you must be a good person. You received a diploma, so you must be educated.

If we focus on specifically on grades and the diploma, we can extrapolate to the problem:

To determine if someone deserves the diploma, we need a benchmark. That benchmark is a grade. But to ensure we get a viable determination of the quality of that student, it needs to be treated like a science; Controlled variables and independent variables. Therefore, everyone needs to be taught the same thing and given the same test to ensure that we can accurately calculate whether the benchmark was achieved for receipt of the diploma.

Yet, life doesn’t particularly care about that benchmark. The market, personal and professional relationships, and the politics of life don’t depend on that benchmark. And what we’re left with is a student body that has lost what should make our species so fantastic.

Creativity.

The ability to connect the dots is an exercise in creativity. But when the focus is entirely on uniformity with the goal of collecting dots, that creativity disappears.

Knowledge is Free

In the 21st century, I can find anything that my professors taught me online. For free. I can combine my interest in bitcoin, sustainability, and biology into one project and find the information I desire. That doesn’t cost me a penny.

Even more, if I want to learn a specific skill, such as programming, writing, or cooking, I don’t need to drop $100,000. Instead, I need to go to YouTube and start watching. Or perhaps I drop $24.99 a month at Lynda.com and gain access to all the curated information I need for a ton of different professional skills.

Do you know how long it takes to fill the cost of a monthly subscription in Lynda.com into $100,000 in tuition? 333.4 years.

There are so many sources of knowledge today that a person’s bag of dots can be as full or as empty as they choose. And the costs are so minimal that anyone can be an expert in a topic quickly. If you’re not sure where to go, just check out this list:

Coursera

Khan Academy

Udemy

edX

Lynda

You’re able to learn about so many different topics — from so many different schools — that you can get started on a path toward becoming an expert on most topics.

Creativity Leads to Innovation

Why do we go to school and seek to gain knowledge? If it’s because of the same reason that I learned growing up, you go to school so that you can get a degree with the ultimate goal of getting a good job.

But by using a “collect the dots” rather than “connect the dots” mechanism, the type of employee that a company gets is one that can regurgitate information, but is incapable of seeing how different variables connect. Further, the frustration that comes from being unable to see how things connect leads to an unmotivated and demoralized environment.

Imagine that you are a marketer tasked with increasing sales for a client. You know that giving content away at the top of the funnel is an effective way to start the conversation, but you’re finding it difficult to get new people to see that you have the content in the first place. You can use PPC advertising, but you want to get more organic and social traffic.

Someone who knows marketing continues to share that piece of content, trying to build links, hoping that people convert. But an innovator — someone who is creative and can connect the dots — knows that a piece of content within a larger piece can be enticing enough to get a share. With a simple change, the same person who is downloading your main piece of content is also sharing it.

How to Learn Connecting the Dots

To be able to connect the dots, you need to be able to visualize your arsenal of dots. If you asked me all the topics that I have at least a moderate understanding of, I would be able to name ten probably. If you gave me a piece of paper and said, “take ten minutes a day and write every topic you know and every topic off that topic and come back to me in a week,” the number of topics would be significantly greater.

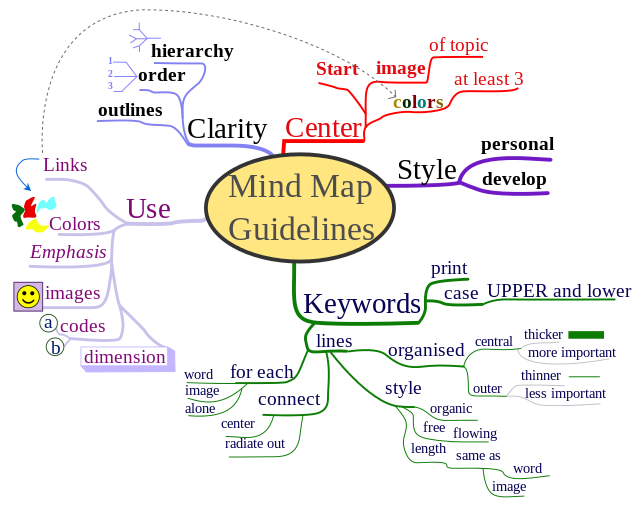

What I just described is a mind map:

This is a guideline on how to do a mind map from Wikipedia.

Soon enough, you can start seeing where separate dots might connect with each other. Perhaps you learned something in a lecture you went to that connects to a class you took in college, which when you combine the two might connect to something else. Soon enough, a dot is connecting to another dot.

Ultimately, the ability to connect the dots requires that you believe that you are proficient in something, which brings us back to building your arsenal of dots. You should always be learning and expanding the dots that you can connect on your mind map. You might never know how a new dot can bring a new connection to your life.

You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. — Steve Jobs

Are Colleges Useless?

I would argue that, in their present form, colleges are not nearly as effective as they were last century. While I enjoyed college and met some of my best friends, I don’t believe the $100,000 that was invested was worth what I gained from it vis-à-vis my education.

Some might argue that the benefit of college is building a network. However, with LinkedIn and Meetup groups, you can build a network of like minded people without needing to spend $100,000. I can talk with dozens of bitcoin enthusiasts right here in New York City; I doubt more than a few of my former professors know anything about bitcoin.

Unfortunately, our society still depends on proof of your success: diplomas. Therefore, I have developed a philosophy about going to colleges. The rules are as followed:

- Ivy League schools remain one of the best investments because their name carries tremendous weight.

- If you’re not accepted to an Ivy League, never go to an out-of-state unless the school is known for a specific field where having its name on your diploma will help in the hiring process.

- Avoid an in-state private college unless the amount of money that they are providing plus your in-state grants will cover the vast majority of the costs.

- Go to a public state college.

I live in New York and I went to a small, private college that was known for two fields: nursing and education. I did not go there for nursing and education. I should have gone to a public state college. The education I would have gotten at SUNY Binghamton or SUNY Albany would have been just as good as what I received where I went.

But more than that, I would currently be in a better economic situation. Even with a tremendous amount of grants and scholarships, I still graduated with $40,000 in student loans. What could I do if I wasn’t making payments on those loans? What would an additional $400 a month look like for my stock portfolio? Perhaps I could take greater risks and create a company. Or maybe I could travel the world — building a bigger arsenal of dots — which would come in handy when I connect each one.

I agree with Mr. Godin: Schools need to get out of the business of teaching how to “collect the dots” and, instead, should teach how to “connect the dots.” One is far more useful and rewarding than the other.

Thanks for reading this. This is my first post on Steemit, primarily because I wanted to test it out. I am a writer for CoinDesk, EIC of Crypto Brief, and Founder of Distributed Studios. While Bitcoin is a big part of my life and is where I do most of my writing, education is a topic that I have always found so fascinating. I would love to hear your opinion on it and encourage you to leave a comment. If you know anyone that is looking at colleges, consider sharing the rules I’ve developed. The money saved can have a lasting, life-long impact.

You know that studying abroad can both cheaper and more educational.

It's my understanding that in Germany you can go, be taught in English and be subsidized. I might be mistaken but anyone looking to choose where to learn it's worth reading up on.

Yeah, that's a very good point. And as an American, you'd gain two things by going overseas to learn:

Thanks for your comment. :)

I've been thinking about this a lot lately. I'm working through a PhD program right now, so I've been up close and personal with the American university system and thinking a lot about what my role will be in the coming years. I'd love to keep in touch with you and keep the conversation open about the future of academia.

What are you studying?

Electrical engineering. My research includes a lot of game theory and analyzing the interactions between social systems and engineered systems.

It's interesting ... I view what you're doing as one of those cases where college could be very necessary. You're learning from expert electrical engineers, you're being guided as you specialize in something. So for that, it makes sense.

But I have a degree in history. Did I really need to go to school for that? If you saw my bookshelf, there are more books on it about historical topics than most of my college text books. :)

Right, the need for college is very context-specific. And PhDs in particular need to come from universities, basically by definition.

But I'm guessing you'd be surprised about the need for college in engineering: I'd guess that somewhere around half of all engineering jobs could be taught perfectly well by apprenticeship rather than university. While I was in college, I had an internship with an industrial automation company; we programmed assembly lines and robots and such, and some of the best engineers in the company didn't have a degree. In terms of real-world "this is how you get it done" sorts of things, I learned at least as much from that company as I did from my classes