In 1866, Odoardo Beccari encountered a flower in Gunung Matang, west of the Malay state of Sarawak. Throughout his life, Beccari discovered and categorized hundreds of plant species, but that plant was never found again. It became an icon, an unknown.

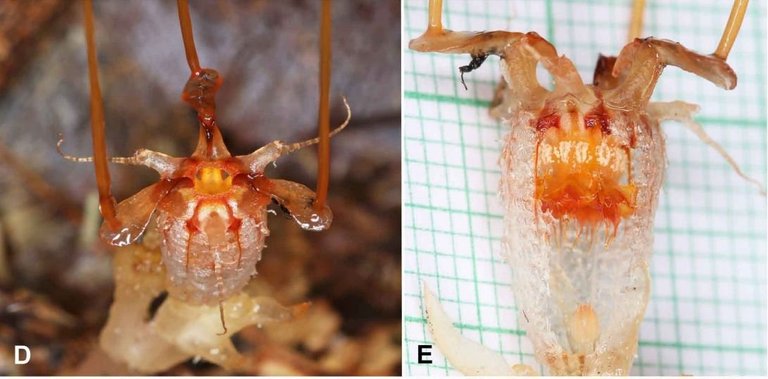

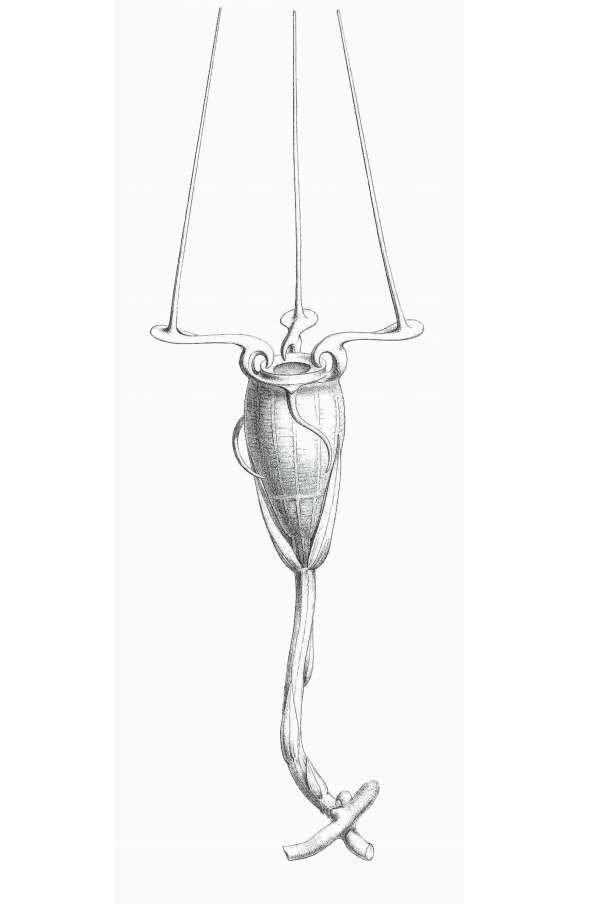

Until in 2017, a team of Czech researchers working in the area realized that there was something that rose about nine inches off the ground and looked like an insect. It was the Thismia neptunis, the ghost flower of Beccari.

The long journey of Beccari and the rediscovery of its flower

The story of Beccari is fascinating. A Florentine orphan who managed to graduate from the Universities of Pisa and Bologna before finishing at the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew, near Richmond upon Thames (London). There he met Darwin, the Hookers and James Brooke, the first Raja of Sarawak. Thanks to this, he spent three years in Borneo, Indonesia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea.

It is known, above all, to find the Amorphophallus titanum, a plant that produces an inflorescence in spadix so large that it is often called "the biggest flower in the world". The one of the Botanical Garden of Edinburgh has gotten to weigh 153.9 kg.

However, in front of the spectacular nature of the Amorphophallus titanum, the mystery of the Thismia neptunis has intrigued scientists for a century and a half. Now we know why: small, rare and with a flowering that lasts only a few weeks, "our limited knowledge of their distribution" is explained because "they can easily be overlooked in the field," the researchers say.

But the botanical community is not only surprised by having (delighted) found the plant, they are by their characteristics. T. neptunis belongs to a group known as mico-heterotrophic plants, that is, plants that use fungi as a source of food instead of photosynthesis.

Of course, the plant does not have chlorophyll, it does not have leaves and, as if that were not enough, it had no plant form. That was precisely one of the reasons that made him doubt his existence: the very rare Beccari drawings. And the curious thing, seeing the current photos, is that the 1866 drawings are really accurate. Nature is fascinating.