My prior blog presciently issued a stern warning about ICOs roughly 2 days before China’s crackdown that coincided with a significant decline in the market.

Every major nation I’ve googled, including even India and the EU, disallow issuance of unregistered securities to non-accredited investors without an appropriate equity crowdfunding (aka crowd equity) exemption.

WARNING: Decentralized ledger tokens issued as securities (and even if with a legal registration exemption such as initially issued only to accredited investors, crowd equity, or even if registered), aren’t ever legal to trade on unregistered exchanges (unless perhaps they are held for 3 years before trading). The pitfalls and implications are convoluted. I analysed in detail at a Bitcointalk post.

Unregistered securities are restricted from public offering to non-accredited investors except if registered and traded on regulated (stock) exchanges. Yet said tokens are technologically enabled for unrestricted trading on unregulated exchanges; which potentially opens Pandora’s box of multijurisdictional legal jeopardy for issuers, exchanges, affiliates, and maybe even traders of the tokens. Afaics, even Filecoin’s SAFT investment structure doesn’t entirely ameliorate this issue.

I. Tokens Which Are Securities

It’s reasonable and presumably sufficient to analyse the USA securities law to determine what constitutes a security in all global jurisdictions (but not for arriving at the analysis other more complex aspects of securities law such as registration, exemptions, enforcement, brokers, underwriters, etc.), because this narrow facet of the securities law it’s ostensibly objectively canonical (irreducible, comprehensive), presumably the most stringent, has similarities to securities laws in other major nations such as Japan, and moreover since for our purposes of analyzing the large scale global issuance of a decentralized ledger token, it’s quite implausible to presume every USA investor could be reliably or provably excluded anyway.

When some incorrectly assert that tokens can’t be securities because they convey no voting rights, they’re only considering the “stock” type in the enumerated list of many common types of securities.

The “investment contract” type of security has four criteria as provided by the Supreme Court’s Howey case:

- transfer of money or value

- profit expectation

- common enterprise

- investors rely on managers of the common enterprise

The first two criteria considered jointly are a subset of1 investment or speculation.

The legal definition of common enterprise is crucial to limiting the applicability of the criterion. It’s well argued that only the “horizontal commonality” jurisprudence is correct and acceptable. The invested funds or value must be pooled into a common enterprise which has managers which the investors rely on for their profit expectation. Note even if the investors are actively involved (i.e. not passive), the existence of managers of the common enterprise is sufficient to meet the criterion’s threhold:

SG Ltd., 265 F.3d at 55 (quoting SEC v. Glenn W. Turner Enters., 474 F.2d 476, 482 (9th Cir. 1973):

“The courts of appeals have been unanimous in declining to give literal meaning to the word “solely” in this context, instead holding the requirement satisfied as long as ‘the efforts made by those other than the investor are undeniably significant ones, those essential managerial efforts which affect the failure or success of the enterprise.’”

Lino v. City Investing Co., 487 F.2d. 689, 692 (3d Cir. 1973):

“an investment contract can exist where the investor is required to perform some duties, as long as they are nominal or limited and would have little direct effect upon receipt by the participants of the benefits promised by the promoters”

Any obfuscations, disclaimers, or “gloss” spin1 such as (for example in EOS’s prospectus) “the token has no value” or “is only sold for its utility and not speculative value”* are irrelevant. Regulators and courts distill to the underlying economic reality,1 which in the case of ICOs always have a profit expectation.1

The SEC wrote on page 11 of their DAO report:

This definition embodies a “flexible rather than a static principle, one that is capable of adaptation to meet the countless and variable schemes devised by those who seek the use of the money of others on the promise of profits.” Howey, 328 U.S. at 299 (emphasis added) … In analyzing whether something is a security, “form should be disregarded for substance,” Tcherepnin v. Knight, 389 U.S. 332, 336 (1967), “and the emphasis should be on economic realities underlying a transaction, and not on the name appended thereto.” United Housing Found., 421 U.S. at 849.

* Additionally the Risk Test applies in 16 States and only requires the risk of losses instead of a profit expectation. Thus the dubious obfuscation of the profit expectation by claiming a token is only purchased for its “utility value”, still encumbers the token as a security in 16 States due to said jurisprudence Risk Test criterion.

A. Purpose of Securities Regulation

Where managerial efforts of others are securing the investors’ profit expectations, the investors holding the securities are reliant on the control of those managers instead of their own interaction with the free market:

I believe that distinguishing between profits realized from the promoter's activities and profits realized from the operation of market forces coheres with the belief that investors are protected by access to information. When profits depend on the intervention of market forces, there will be public information available to an investor by which the investor could assess the likelihood of the investment's success. Thus, for example, a purchaser of silver bars has access to information on the trends in silver prices, an investor in paintings can get a sense, at least generally, of how the market for artwork is faring, and a purchaser of an undeveloped lot has access to information on growth trends in the area. Obviously, the degree to which this information is actually available to an investor depends on the sophistication and education of an investor, but that is true about investments generally. Moreover, where profits depend on the operation of market forces "registration ... could provide no data about the seller which would be relevant to those market risks." SEC v. G. Weeks Securities, Inc., 678 F.2d 649, 652 (6th Cir.1982).

Where profits depend on the success of the promoter's activities, however, there is less access to protective information and the type of information that is needed is more specific to the promoter. Given the pivotal role of the promoter's activities, what the investor needs to know is not generally how this type of activity has fared but what the specific risk factors attached to the investment are and whether there is any reason why the investor should be leery of the promoter's promises.

Securities regulation is intended to require that investors are given all the material facts (except for non-publicized issuance to only accredited investors), to regulate how much non-accredited investors can risk (for their own protection and to mitigate threat of widespread financial instability), and hold managing issuers responsible for non-factual statements and fraud. And to control where securities can trade, so that enforcement and restitution is plausible.

The SEC wrote on page 11 of their DAO report:

The test “permits the fulfillment of the statutory purpose of compelling full and fair disclosure relative to the issuance of ‘the many types of instruments that in our commercial world fall within the ordinary concept of a security.’”

B. Ethereum and Every ICO With Funded Developers/Managers

I disagree with those who opine that Ethereum might not be a security1 due to the theory that investors expected only the store-of-value where no profit in the form of dividends would be paid.

The SEC wrote on page 11 of their DAO report:

“[P]rofits” include “dividends, other periodic payments, or the increased value of the investment.” Edwards, 540 U.S. at 394.

The peer-to-peer tradeable ETH token didn’t even exist when the token sale for rights to the ETH token completed. In order to obtain a functional ETH token, the investors relied on the ongoing managerial efforts of the common development enterprise which was in control of the pool of funds from the token sale.

Additionally, @mining1 — one of the prominent shills for Ethereum — told me in BCT private messages (and afair may have even alluded to in some public posts) that Vitalik’s persona is the main and most irreplaceable factor for Ethereum’s investor confidence, which was demonstrated by the preferences of more investors for Vitalik’s hard fork of ETH versus the immutable ETC. These are the sort of insider revelations that regulators discover when they investigate,1 which can strengthen an enforcement case. Whereas, investors’ profit expectations don’t rely on ongoing efforts from Satoshi Nakamoto nor Hal Finney. I’m dumbfounded as to how anyone who is fully informed could conclude that ETH issued in the token sale is not a security. Those ETH tokens issued as securities have been presumably mixed with the legal non-security proof-of-work mined ETH issuance, causing all ETH to contain some traces of and thus become securities.

The SEC wrote on page 13 of their DAO report:

DAO Token holders were substantially reliant on the managerial efforts of Slock.it, its co-founders, and the Curators. Even if an investor’s efforts help to make an enterprise profitable, those efforts do not necessarily equate with a promoter’s significant managerial efforts or control over the enterprise. See, e.g., Glenn W. Turner, 474 F.2d at 482 (finding that a multi-level marketing scheme was an investment contract and that investors relied on the promoter’s managerial efforts, despite the fact that investors put forth the majority of the labor that made the enterprise profitable, because the promoter dictated the terms and controlled the scheme itself).

C. Non-competitively Issued Tokens

Any token which was premined or non-competitively issued and then sold to raise funding for ongoing managerial and/or development efforts which the investors’ profit expectations rely on, has the same economic reality as an ICO issued token and thus is a security.

Since the tokens have been effectively self-issued to the issuer at no appreciable market competitive cost, the issuing manager(s) of the common enterprise to which the purchasing investors rely on, have pooled the investors’ funds fulfilling the “horizontal commonality” definition of the common enterprise criterion. Even if not all tokens are securitized, ditto per the explanation in the prior section, the securitized tokens become mixed with the non-securitized such that all tokens become afflicted.

Afaics, Steem, Dash, PIVX, and Bytecoin are examples of these deceptively issued securities which violated AML and securities regulations. And there’s the documented fraud in Dash’s deception and misrepresentations of material facts.

Even though these issuers attempt to obfuscate their coordinated managerial efforts by claiming that the control of the enterprise is in the voting power of the proof-of-stake for Steem or masternode stakes for Dash/PIVX, the SEC’s DAO report exemplifies they’ll distill to the economic reality:

Thus, the Curators exercised significant control over the order and frequency of proposals, and could impose their own subjective criteria for whether the proposal should be whitelisted for a vote by DAO Token holders. DAO Token holders’ votes were limited to proposals whitelisted by the Curators, and, although any DAO Token holder could put forth a proposal, each proposal would follow the same protocol, which included vetting and control by the current Curators. While DAO Token holders could put forth proposals to replace a Curator, such proposals were subject to control by the current Curators, including whitelisting and approval of the new address to which the tokens would be directed for such a proposal. In essence, Curators had the power to determine whether a proposal to remove a Curator was put to a vote.

In the prior section, I alluded to the SEC’s whistle-blower bounties1 offered to encourage insiders to squeal on each other, so as to provide the details to document the control of the insiders.

As a separate concern to the aforementioned analysis of whether the tokens can be proven to be securities, the self-issued tokens must be spent only on goods and services otherwise each self-issued token seller must register as a money services business and comply with AML regulations. FinCEN’s enforcement against Ripple is an example of the possible punishment for not complying. And apparently the authorities were reasonably lenient on Ripple because Ripple was trying to work with the authorities to correct their mistake.

Afaics, no security is created if the self-issued tokens are only spent (directly without any intermediary Bitpay or ShapeShift exchange) on genuine goods and services which aren’t a structured obfuscation of an investment in the transferred tokens:

The SEC wrote on page 11 of their DAO report:

Uselton, 940 F.2d at 574 (“[T]he ‘investment’ may take the form of ‘goods and services,’ or some other ‘exchange of value’.”)

Or only sold to investors after they no longer rely on the managerial efforts of the seller of the self-issued tokens. But note there’s a jurisprudence minority dissenting opinion which argues that pre-purchase managerial efforts could possibly securitize the investment if market forces have not yet diminished the significance of the said efforts:

The majority instead takes the position that in order for Howey 's third prong to be satisfied, the promoter must perform managerial and entrepreneurial activities after the investment is purchased. Maj. op. at 313-14 […] I believe that the third prong of the Howey test can be met by pre-purchase managerial activities of a promoter when it is the success of these activities, either entirely or predominantly, that determines whether profits are eventually realized […] On the other hand, if the realization of profits depends significantly on the post-investment operation of market forces, pre-investment activities by a promoter would not satisfy Howey 's third prong.

Additionally, tokens aren’t securities when issued by a common enterprise at no charge to users who aren’t managers of the common enterprise, because when those users sell or spend their tokens, they’re not transferring the funds, goods, or services to the pool managed by the common enterprise.* Thus, airdropped issuance such as Byteball wouldn’t be a security unless as @cryptohunter had posited could be a possibility, there was collusion with exchanges who received free tokens and provided kickbacks or otherwise transferred value back to the issuer’s enterprise.

And the admirable implication is that self-issued tokens can’t be legally spent until the token becomes an actual currency that can be directly (i.e. not exchanged by Bitpay or ShapeShift) spent on goods and services of value to the issuer. And can’t be transferred to an investor until the self-issued token seller is no longer managing the common enterprise which investors rely on for the profit expectation.

* Note the classification as a non-security wouldn’t necessarily hold if a “vertical commonality” instead of the “horizontal commonality” definition of common enterprise was applied, but it’s likely that only “horizontal commonality” will prevail in jurisprudence.

D. Legal Jeopardy of Selling Tokens to the Public

Selling highly tradeable instruments to the public is fraught with potential multi-jurisdictional legal jeopardy.

For example, the Useless Ethereum Token may not be a security because it appears to actually douse any investor expectation of managerial efforts by the issuer, if the promises of non-declining price and ongoing price manipulation are construed by investors to be jokes. The Shit Token appears (with bounties, etc) to create expectations of managerial efforts; thus might be a security. However, both have likely been issued in violation of AML regulations, because the issued tokens were sold (enabling third parties to transmit money to fund their virtual token account) rather than spent on goods and services. Although the Useless Ethereum Token appears to not have mislead expectations which run afoul of MLM laws, nevertheless exposing oneself to the legal jeopardy of “selling snake oil” lawsuits in potentially innumerable jurisdictions seems to exhibit very poor judgement for anyone who has significant opportunity costs — such as wanting to continue to travel and do business internationally.

The similarities to the Dot.Com bubble, public destruction, and fallout repercussions could end up even more egregious if exponential growth of illegal token issuance continues.

E. Bitcoin and Other Tokens Competitively Issued Proof-of-work

Bitcoin, Litecoin, Bitcoin Cash, and other tokens issued competitively with proof-of-work aren’t securities, because none of the funds paid for tokens was pooled into a managed common enterprise.

Although there’s sense of community and shared objectives, the decisions of each actor in the ecosystem is independent and subject to differing individualized conditions in the free market, so applying the “horizontal commonality” definition for the common enterprise criterion, the funds invested by the miners of tokens and the purchasers of tokens don’t get pooled in a managed common enterprise. The developers which manage the open source code (even if it’s argued to be a controlled enterprise) are not funded directly by pooling funds paid for the acquisition of tokens.

Certainly at least in Bitcoin’s case (and thus derivatively Bitcoin Cash also), as evident by someone spending 10,000 BTC on a pizza in May 2010, there was no reasonable profit expectation during the period in which those — who had mined self-issued coins with very little market competition — were still the managers of the code. And apparently Satoshi didn’t sell any of those self-issued BTC, neither during the period when he was managing the code or ever.

II. Likely Forms of Regulatory Enforcement Worldwide

Whac-A-Mole enforcement action against innumerable token issues involving issuers and traders in numerous jurisdictions is beyond the reasonable enforcement resources of regulators.1 IOW, analogously the enforcement agencies are likely to prioritize punishing1 the Bernard Von Nothaus and Kim Dotcoms, rather than the users as was afaik the case for the Liberty Dollar and Megaupload.

Extradition can proceed

There’s an unscientific poll to collect readers’ opinion as to whether this section will come to fruition.

A. Exchanges Will Capitulate

Thus, with the culpability of exchanges mentioned briefly in Sections II-B-3 on page 8 and III-A on pg. 10 and extensively in section III-D on pp. 16-18 in the SEC’s DAO report, rather than to go after individual issuers and/or traders except perhaps in egregious cases and especially those with rampant fraud,1 money laundering, and/or many victims,1 legal experts warned that regulators are most likely to prioritize enforcement actions against exchanges1 within their jurisdiction because exchanges are large economy-of-scale targets which trade many potentially illegal tokens making the enforcement court case stronger and more efficient. China’s enforcement action against 60 exchanges (and ICO issuance platforms) served as an example confirmation of regulatory priorities.

So the regulators will not even in most cases need to bring an enforcement case against each token alleged to be an illegal security. Merely threatening enforcement1 against exchanges will be enough for the exchanges to voluntarily delist those tokens which could plausibly be construed to be illegal securities, because virtually no one wants to fight the government in court.1 We see this in action already with multiple high-profile Chinese exchanges voluntarily shutting down or delisting, and even high-profile non-Chinese exchanges ShapeShift and Bitfinex have announced voluntary delisting of suspected tokens1 (c.f. ShapeShift’s blog statement and Bitfinex’s announcement).

Some postulate that decentralized exchanges could displace centralized exchanges if regulators aggressively delist tokens. Since Bitcoin (given it’s not a security) would continue to be accessible on centralized exchanges for users wishing to convert fiat to cryptocurrency, it’s technologically possible to continue to trade (on decentralized exchanges) with delisted tokens, but truly (e.g. not Bitsquare) decentralized exchanges have pitiful liquidity and moreover the factor explained in the next sub-section is likely to disincentivize the vast majority of investors from trading these illegal securities which (as explained in the next sub-section) they must report to the authorities.

So I remain of the mindset that issuing tokens that could be delisted in the future by exchanges is irresponsible if a development group is sincere1 about the long-term viability of the token. Thus IMO dubious or illegal issuance is the signpost of projects that will fail to produce any significant or lasting real world use case and adoption (other than selling empty bags to greater fools), analogous to those Pets.com examples from the dot.com bubble.

James A. Donald — the first person to interact with Satoshi Nakamoto on the mailing list — wrote:

Every website reporting on the altcoin boom and the initial coin offering boom has an incentive to not look too closely at the claimed numbers. Looks to me that only Bitcoin and Steemit.com have substantial numbers of real users making real arms length transactions […] The crypto coin business is full of scammers, and there is no social pressure against scammers, no one wants to look too closely, because a close look would depress the market. There is no real business plan, no very specific or detailed idea of how the coin offering service is going to be of value, how it is going to get from where it is now, to where it is going to usefully be […] Nearly all of them are furtively centralized, as Bitcoin never was. They all claim to be decentralized, but when you read the white paper, as with Waves, or observe actual practice, as with Steemit, they are usually completely centralized, and thus completely vulnerable to state pressure, and quite likely state seizure as an unregulated financial product, thus offer no real advantage over conventional financial products. When you buy an initial coin offering, you are usually buying shares, usually non voting shares, in a business with no assets and no income and no clear plan to get where they will have assets and income, as in the dot com boom.

B. Investors Will Capitulate

There’s a significant difference for illegal token trading versus the illegal downloading of copyrighted media, in that investors in many nations are required to report capital gains to tax authorities and there might even be coming legislation which requires declaring all token holdings when crossing a border and on annual tax reporting. Thus there’s already a legal framework for tracking individual holdings of tokens, which could potentially be leveraged for enforcement of AML, MLM, and securities regulations that pertain to tokens.

Fact is that the developed nations which have the money to invest also have the lowest rates of shadow economy tax evasion.

Irwin Schiff Famed Tax Protester Dies In Prison

III. Fundraising Without Issuing Tokens As Securities

As I understand so far, there are basically three legal alternatives which are appropriate for different situations and stages of the project development:

| Source | Reach | Stage | Applicability | Legal Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC angels | VCs | early concept | managed centralized | SAFE or convertible note |

| crowd equity | single nation or the EU | established corporation & project | managed centralized | Regulation D, A+, CF in USA; SEIS/EIS in UK, etc. |

| DAO | global | all | unmanaged decentralized Inverse Commons | n/a |

As previously mentioned in sections I-E. Bitcoin and Other Tokens Competitively Issued Proof-of-work and I-C. Non-competitively Issued Tokens, decentralized ledger tokens aren’t securities if issued by either competitive proof-of-work or the non-securitization options described in that latter section. The investors receive their ROI via dividends of the revenue of the centralized corporation or decentralized royalties of the DAO.

A. Venture Capital

The SAFE or convertible note doesn’t avoid the investment being securitized, and are mainly for facilitating taking equity funding before a pricing round.*

VCs typically valuate the startup far too low and want to direct your company towards a centralized corporation structure future conducive to eventually issuing an IPO or acquisition.

Alternatively, the non-selective (thus presumably applicable to early concept stage) crowd equity platform Wefunder takes 20% equity from the investor plus 7% fee from the issuer, but limited to USA investors, $1m from non-accredited investors per year, and if the fundraising is public then the legal costs and reporting compliance are “medium”.

Raising private equity from investors all over the globe can be thorny, e.g. Canadian complexity.

* There’s no plausible way to in the future convert a debt repayment (or SAFT warrant) to decentralized ledger tokens which aren’t securities, that is not equivalent to repaying the debt and the lender purchasing the tokens at the market price. Thus for the investors to attain an ROI on tokens that is greater than a fixed interest rate, the tokens will be securities.

Ditto legally compliant platforms (e.g. not Fundable nor Crowdfunder) select for patterned centralized corporation structure future conducive to eventually issuing an IPO or acquisition; thus aren’t structurally (investor goals) compatible with decentralized ledger projects because capital gains on peer-to-peer tradeable tokens (even with the Filecoin SAFT) creates illegal securities per the warning at the start of this blog. At this nascent juncture of investment in and adoption of decentralized ledgers, investors want capital gains on token appreciation, not capital gains on market valuation of future app revenues. Although hypothetically a decentralized ledger app developer could generate revenues and aim towards capital gains on the shares via an eventual IPO or acquisition, the gains from token appreciation are likely orders-of-magnitude greater than the revenues for app fees (considering a decentralized ledger disintermediates parasitic middlemen by increasing open competition to provide general app infrastructure at lower fees and most revenues accrue to vertical market apps and/or between end users). Thus investors would desire for revenues to be distributed asap as dividends (possibly taxed as income), so they can hold tokens at the lowest possible basis price for future capital gains taxation.B. Crowd Equity

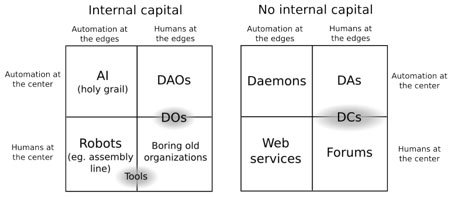

C. Decentralized Autonomous Organization

DAOs, DACs, DAs and More: An Incomplete Terminology Guide

“The DAO” tokens created by Slock.it were securities primarily because the investors relied on the efforts of Slock.it ongoing,1 i.e. there was asymmetrical privileged managerial control for the Curators compared to other investors. Additionally the investors’ funds were pooled and thus could be managed by others.

Reformulating a DAO with symmetrical management control could possibly be insufficient, because the securities law applied to partnerships (and LLCs) exemplifies that due to implausibility of independent control in a collective (i.e. Vitalik’s “automation in the center” doesn’t empower each investor’s profit expectation as independent from the others), any form of common enterprise that passes through shares of generated revenues to (even non-passive) partners may risk being a security.1

For avoiding securitization, much better each investor independently manages and funds a developer (or developers) to produce a revenue generating app. Investors of apps can voluntarily donate say 20% of their developer resources to joint open source development of the decentralized ledger upon which they’re building their apps. The non-profit open source collaboration on the decentralized ledger is not a security because there is no share of its profits. Thus necessarily these investors can’t partake of any (portion of any) premine of the decentralized ledger nor be contractually promised any ROI in terms of quantity of decentralized ledger tokens,* else the said tokens are securities and could be delisted and shunned by investors in the future per the prior section II. Likely Forms of Regulatory Enforcement Worldwide.

Hypothetically such an investment structure wouldn’t be burdened with securities compliance; and thus could be publicly promoted and accept (even non-accredited) investor participation globally. Yet it’s dubious whether such a structure could function well enough given investors aren’t developers (they’re really passive).

Each investor should probably form a limited-liability company to limit their liability.

* Premine (and obfuscated equivalents) can only be awarded to an entity (or entities) whose investment profit expectation (even possibly applying also to investment of development effort directly transferred to the open source code asset pooled in a common enterprise but not some indirect infusion of diversified free market activity) isn’t significantly dependent on some common enterprise to which (presuming only “horizontal commonality”) said transferred investment value has been pooled such that it is controlled by managers who aren’t said entity. So afaics (other than tokens awarded where no value is directly transferred for investment as mentioned in section I-C. Non-competitively Issued Tokens) only the entity which has exclusive managerial control on decentralized ledger source code qualifies (unless it was plausible that no one controlled the decentralized ledger source code) because the control of the value invested (in the source code) is never transferred to another manager. It’s presumed the premine is only exchanged for development effort investment in the source code since it’s the separate enterprise where the premine is created, and not for other value transferred to some common enterprise, yet to avoid ambiguity ideally the said entity should have managerial control everywhere it/he/she contributes work unpaid which could possibly otherwise be construed to be investment in some common enterprise. And these self-issued tokens can only be later transferred per the stipulations in the section I-C. Non-competitively Issued Tokens.

Low-risk, High-reward Joint Efforts

Additionally, given that the tokens earned by apps (and any premine of the decentralized ledger not awarded to said investors) wouldn’t be securitized by any securitization of the pooling of the enterprise to develop said apps (and donating developer resources to the open source decentralized ledger development). Thus, the investors (each protected for liability by forming limited-liability company or equivalent in their jurisdiction) could decide to form a joint venture common enterprise (of any legal form even just a contractual partnership, perhaps even administered on decentralized ledger although note that Aragon ICO-issued tokens are illegal to spend) to pool their efforts, risking only civil fines (because any regulation enforcement disgorgement of funds raised would be returned to themselves) presuming they’ve committed no fraud to justify criminal prosecution. And the risk of said enforcement (especially if the organization was done privately with obviously sophisticated investors employing no public advertising and the total funds raised wasn’t huge) would be very remote in the (presumably “not legal advice”) opinion of a former SEC enforcement attorney.1

Each investor could independently decide whether to send his/her portion of the periodic payments to contracted developers. The payments not made by investors that decline to fund their (joint venture) agreed share for a given period, can be voluntarily made by the other investors or the developers can reduce the hours they work. All funds contributed are tallied and the developed apps which run decentralized, make royalty payments in tokens on the decentralized ledger directly to each investor proportional to the shares of funds contributed. This sort of “automation in the center” doesn’t constitute managerial efforts for a security:

…they have never suggested that purely ministerial or clerical functions are by themselves sufficient; indeed, quite the opposite is true […] LPI characterizes these functions as clerical and routine in nature, not managerial or entrepreneurial, and therefore unimportant to the source of investor expectations; in sum, anyone including the investor himself could supply these services. The district court seemed to agree with LPI about the character if not the significance of most post-purchase services, for it described them as “often ministerial in nature.”

The investors in the joint venture could vote when necessary to make collective managerial decisions about which developers to enter into a contract with or to stop contracting, but each investor can independently opt-out of funding any specific contracted developer as aforementioned. The opt-out however doesn’t ameliorate the reliance of the already committed investment on the ongoing joint managerial efforts, so each investor is not entirely independent, yet neither are partners in general partnerships which historically weren’t subject to securities regulation. If the investors are sophisticated and active in evaluating development progress, the organization may be construed as analogous to a general partnership w.r.t. to the securitization concern.

The level of decentralization of control of investors is dependent on the level of decentralization of the development and deployment of the apps. Thus an Inverse Commons open source process combined with the aforementioned automated royalty functionality provides for a higher level of decentralization and less risk of the organization being categorized as a securitization of pooled investment funds.

Yet it’s dubious whether such a structure could function well enough.

1 Let’s Talk Bitcoin episode #198 Nick Morgan: The DAO, the SEC and the ICO Boom

Disclaimer: IANAL. This is not legal advice.

High quality article as always anonymint. It is hard to understand all of them ( due to terminology and because i am an average English speaker ) but i always learn something new.

Ty. I put so much effort into this blog because it’s necessary to write all of this down (and have it peer reviewed) so we make sure that my decentralized ledger project is issued and structured legally.

Hey, how is your project (bitnet) getting along? Is it still a thing or have you given up?

We are trying to move forward. We were slowed down while analyzing the impact of securities law and devising how we can onboard millions of users without creating a security.

We’re also slowed down by my attempt to recover from gut Tuberculosis and my variable liver health condition (bad liver impacts energy and causes toxic brain dementia/delirium). I took on some loans and am trying to hire another lead developer (hopefully top-notch from outside the crypto sector) who is younger and healthier than me so I can impart knowledge.

See the other reply I made today.

The author is clearly most interested in scaring the bejeezus out of joe six pack coin investors. The language reads like a scare monger how to guide :

Clearly the SEC is going to focus on cases that involve fraud. That being said, why bother with the risk? Here are some tips to avoid conflict with the SEC:

The ICO market, just like many other industries before it, will flee from the US if the US has a bloated and costly regulatory framework for the industry. US politicians seem to never learn their lessen, hence the hollowing out of the US economy, which produces little, consumes a plethora, and has had a negative trade balance for decades. 20+ trillion in national debt is a ticking time bomb and choosing to domicile outside of that time bomb has some very attractive advantages the day that the US misses a T-Bill coupon payment!