ŠLECHTIC OD CEPU

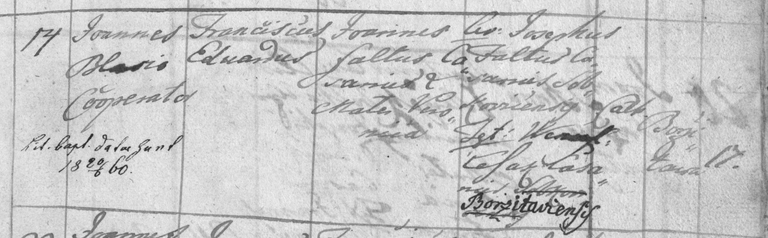

František Eduard Faltus, * 14.10.1773 Bořitava 14, † únor 1857 Trnava, invalidovna

.

Série “Šlechtici od Orlice” prozatím končí příběhem Františka Faltuse, který se šlechticem doopravdy stal. Zní to jako pohádka, ale zároveň se vkrádá otázka… Povýšili byste právě jej?

Začalo to tenkrát, když se Čechy vzpamatovávaly z posledního velkého hladomoru. Zatímco ve druhé polovině roku 1772 se ve farnosti Nekoř ubíralo na věčnost několik desítek lidí měsíčně, od února 1773 se umíráček rozezněl za stejný čas sotva několikrát. Devět měsíců poté, co smrt skončila divoký rej, se bořitavskému chalupníkovi Janu Faltusovi a jeho ženě Veronice narodil zdravý klučina. Pojmenovali jej František Eduard.

Vyrostl v chudém hospodářství, ale zdá se, že selská práce mu nevoněla. K příběhu, který popsal Antonín Špinler (1) se pokusím dodat pár podrobností.

Koncem listopadu mlátil starý Faltus se synem Franckem obilí. Skoro dvacetiletý mladík myslel na ledacos, občas vypadl z rytmu a uhodil do tátova cepu. Když se to stalo poněkolikáté, otec se rozkřikl: „Kolohnáte nemotorná, ty mně to děláš naschvál, já tě za to porovnám cepiskem“ a napřáhl cep na syna. Ten na nic nečekal, praštil cepem o mlat a pryč.... Nepřemýšlel kam běží, až se ocitl na Bredůvce u hospody, kde verbíři sháněli vojáky. Francek s hlavou plnou vzteku a vzdoru nad selským údělem neváhal a nechal se naverbovat.

Že odpovídal požadavkům (věk 17-40 let , výška 168–180 cm), verbíři ho přivítali s otevřenou náručí. V kapse mu zacinkalo nějakých deset, patnáct zlatých, které dostávali dobrovolníci u Frei Werbungu závdavkem a v žaludku hřála kořalka, kterou jej důstojník zhusta častoval. “Co bys od rána do večera záda hrbil, s námi se po světě podíváš, hezkých holek všude plno…”, znělo mu v uších. Snad si ve svém rozčilení ani neuvědomoval, že se upisuje nadosmrti (2).

Navlékli jen do bílého kabátu a když skládal vojenskou přísahu, možná už trochu litoval. Kasárnami se nesla slova, která jen málokterému rekrutovi šla opravdu od srdce: "Přísaháme Panu Bohu všemohoucímu tělesnou přísahou, že našemu nejosvícenějšímu a nejmocnějšímu knížeti a pánu Františkovi, uherskému a českému králi, arciknížeti alpských zemí, jakož to nyní regírujícímu dědičných zemí pánu a od jeho Královského Majestátu všem zřízeným pánům generálům a oficírům, jenž nám Jeho jménem nyní i budoucně poroučeti budou, zvláště našim obrštům, obrstlajtnantům a obrstwachmistrům, též ostatním vyšším a podřízeným oficírům poslušni, věrni a služební budeme, jich ctíti a respectivě jich nařízení a zápovědi věrně uposlechnouti, jakož i tahy a stráže ve dne v noci konati, za i před nepřítelem v boji šturmech, potýkáních a ve všech jinších případnostech po zemi a po vodě, kdekoliv se seběhnou a taky, jaká kde Jejich Královskému Majestátu služba potřebná bude, my jako udatní, zmužilí a poslušní se býti proukážeme, tak jak na jednoho každého počestnýho a dokonalýho vojáka náleží a přísluší, dle oných od Jejich Majestátu potvrzených vojenských artikulů ve všech článcích a závěskách, jak sluší se chovati, proti všem Jeho Královského Majestátu nepřátelům bez vejminky vždy dle potřeby počestně, udatně a zmužile bojovati a se potýkati, taky s nepřítelem veskrz žádné korespondence aneb srozumění nemíti, žádný z nás od našeho regimentu, compagnie aneb fangle se odděliti a odstoupiti, nýbrž při živu býti a umříti chceme. Čemu nám dopomáhej Bůh všemohoucí a svaté evangelium skrze Ježíše Krista. Amen!" (3)

Jak dlouhý čas strávil výcvikem lze jen těžko odhadnout – několik týdnů nebo jen pár dní. Záleželo tenkrát na aktuální situaci a potřebě. Základem všeho byl krok. Rakouská pěchota se přesouvala v pochodové koloně o šíři půlkompanie a rychlost přesunů a manévrů byla prvořadá. Žádné raz – dva, ale tři druhy kroků, k nimž nováčky cepovali pořád a pořád dokola… obyčejný (Ordinärschritt) – 95 kroků za minutu, rychlý (Geschwindschritt) – 105 kroků za minutu, zdvojený (Doublirschritt), mimořádně vyčerpávající, používaný výjimečně ke změně formace a k útoku – 120 kroků za minutu.

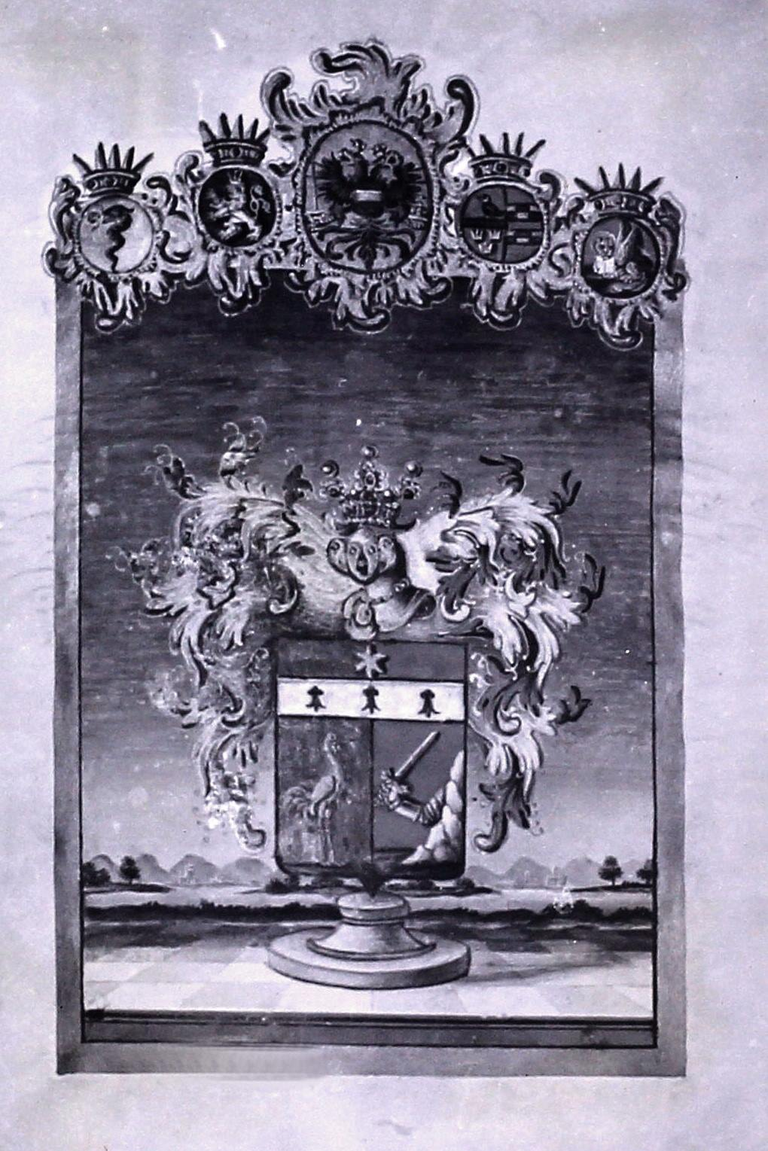

Tvrdý výcvik vydržel se zaťatými zuby. Hulákání a kopance brzy přestaly, protože oficíři brzy poznali, že Francek je voják chytrý a ctižádostivý. Jak by také ne, když uniforma hřála líp, než šaty z režného plátna a jídlo bylo přece jen chutnější než kyselo, brambory na loupačku či podmáslí.... Tak pěšák František Faltus prošlapal celé mocnářství, Bavory, Francii, císař pán vydal ve Vídni 15.2.1824 listinu, kde se m.j. praví: „My, František I., z boží milosti císař rakouský .... bereme a uvádíme na vědomí, že Franz Faltus, nadporučík regimentu pěchoty, s ohledem na získané zásluhy byl povýšen do stavu šlechtického. On totiž začínal jako prostý voják a po třicetileté dobrovolné vojenské službě, během níž se zúčastnil třinácti polních tažení, při kterých tři obležení prodělal zčásti jako poddůstojník, zčásti jako skutečný důstojník a nechal se ku spokojenosti svých představených i k jiným důležitým službám vojenským používat. Proto jsme jako odměnu za tyto zásluhy Františka Faltuse včetně jeho manželských potomků obojího pohlaví pro všechny budoucí časy ... povýšili do stavu šlechtického a propůjčili mu čestné oslovení „šlechtic von“.... Jako trvalý důkaz této naší vůle a povýšení propůjčujeme Františku von Faltusovi následující v barvách navržený šlechtický znak, totiž přesně ve špici se sbíhající červený a modrý po délce půlený ke hlavě znaku směřující štít, který je podložen třemi heraldickými korouhvemi a nad těmito uprostřed v dělení štítu se vznáší zlatá hvězda, vpravo pak v červeném poli na zelené půdě vykročený jeřáb ve zlatě a v modrém poli se z okraje štítu vypíná strmá skála a z ní obrněná paže přísahá taseným mečem se zlatým držadlem.“

Franz Edler von Faltus je v “Militär-Schematismus des österreichischen Kaiserthums” z roku 1831 uveden jako nadporučík (Oberlieutnant) 15. řádného haličského (4) pěšího pluku dona Pedra, císaře brasilského. Ovšem v lidovém podání přetrvávalo označení “regiment Zach”, podle předchozího majitele. V době, kdy František utekl z domova, byly doplňovacím místem odvodů Čechy a pluk sídlil v Chrudimi. Proto je vcelku logické, že skončil v jeho řadách.

Jestliže se stal jeho příslušníkem zhruba roku 1794, zažil nejednu těžkou chvilku. V císařském jmenování se píše o třinácti taženích, jichž se jako voják účastnil. Je pravděpodobné, že byl ve všech významných bitvách proti Napoleonově armádě – u Marenga, Ulmu, u Slavkova, u Lanshutu. Určitě nechyběl 22. května 1809 u Aspern, kde byli Francouzi poprvé poraženi. Mohl být i u Wagramu, u Drážďan, roku 1813 u Chlumce a v půli října téhož roku v bitvě národů u Lipska, kde proti sobě stálo na půl milionu vojáků z celé Evropy. Patrně nechyběl ani 18. června 1815 u Waterloo, v poslední rozhodující bitvě s francouzským císařem.

Dvě desetiletí plná úmorných tažení, krutostí, rabování, hladu, porážek i vítězství. Doba vroubená desítkami tisíc mrtvých. Kolik jich asi zabil někdejší bořitavský mládenec ve jménu císaře pána?

Život mu plynul… no, zkrátka po vojensku. Ráno dril, večer veselí, pitky s kamarády a ráno s bolavou hlavou zase dril. Jeden druhého se snažil přesvědčit, že takhle je jim vlastně nejlíp. Jenomže čas neúprosně běžel a najednou přišlo stáří a nemoci. Stará zranění z probělaných bitev bolestivě připomínala mrtvé, které František poslal na onen svět. Věděl, že už brzy se s nimi setká. A nebyl nikdo, kdo by se postaral.

„Poněvadž v tomto pomíjejícím životě není nic jistého, než smrt, leč hodina její jest nejistá... já Petr hrabě Strozzi, pán na Hořicích... ustanovuji, aby zestárlí chudí důstojníci a vojáci, kteří ve službách válečných zneschopněli, z mého majetku a na něm... zaopatřováni byli jídlem, nápoji, šacením a jinými potřebami, aby na tom žili a nuceni nebyli po věrných a dlouholetých službách válečných žebrati nebo docela ve zkázu přijíti“, napsal hrabě do závěti 3. srpna 1658. A právě díky jemu a dalším mecenášům vyrůstaly zprvu malé ubytovny až konečně v roce 1743 císařovna Marie Terezie pověřila hraběte Štěpána Kinského správou veškeré péče o rakouské vojenské invalidy. Zprvu byl zřízen velký invalidní ústav ve Vídni, poté v Praze a pro Uhry vznikla ústřední invalidovna v Trnavě. Právě tam skončil bezdětný František Edler von Faltus (5) a právě tam v únoru 1857 zemřel.

Jako by nebylo dost na jeho zmařeném životě, před svou smrtí si přál, aby jeho šlechtický znak převezli do domů do Bořitavy, kde měl sloužit mladým chasníkům ku povzbuzení.

Erb spolu se všemi dokumenty dosvědčujícími průběh vojenské služby Františka Faltuse a zásluhy během polních tažení se prostřednictvím okresního úřadu v Žamberku dostal v září 1859 do Bořitavy čp. 19.

Bořitovští sousedé se rozhodli šlechtický erb namalovat na dřevěnou desku, uspořádat slavnost a v jejím průběhu erb připevnit na rodné stavení. Termín slavnosti byl stanoven na 8. října 1877. V tento den ale již od rána hustě chumelilo. Nový termín slavnosti byl tak stanoven na jaro následujícího roku, konkrétně na neděli 12. května 1878.

(1) Antonín Špinler, Lidé od Orlice, Oftis 2004

(2) doživotní vojenská služba byla změněna na 10-14tiletou 2. února 1802

(3) text vojenské přísahy z roku 1805 (převzat z knihy SCHILDBERGER, Vlastimil. Císařská armáda, tažení roku 1805 a bitva u Slavkova. Brno, 1998, s. 11–12)

(4) podle místa doplňovacích odvodů

(5) Franz Edler von Faltus kupodivu napsal i útlou, kupodivu ne vojenskou knížku Ausflüge von Wien nach Maria Zell in Steiermark und seine schönsten Umgebungen o 51 stranách, jež vyšla ve Vídni roku 1842 u Carla Überreutera.

Ve Štýrské státní knihovně mají také mimořádně vzácnou sérii velkých litografických pohledů na Mürztal od Franze Edlera von Faltus, cca z roku 1840.

*

THE NOBLEMAN FROM THE FLAIL

František Eduard Faltus, * 14.10.1773 Bořitava 14, † February 1857 Trnava, invalid

.

The series "Noblemen from the Orlice" ends for the time being with the story of František Faltus, who really became a nobleman. It sounds like a fairy tale, but at the same time the question creeps in... Would you promote him?

It started when Bohemia was recovering from the last great famine. While in the second half of 1772, several dozen people a month were going to eternity in the parish of Nekor, from February 1773 onwards the death knell sounded barely a few times in the same period. Nine months after death had ended the frenzy, a healthy baby boy was born to Jan Faltus, a cottager from Bořiv and his wife Veronika. They named him Frantisek Eduard.

He grew up on a poor farm, but it seems he didn't like peasant work. I will try to add a few details to the story described by Antonín Špinler (1).

At the end of November, old Faltus and his son Franck were threshing corn. The young man of nearly twenty years thought of many things, occasionally falling out of rhythm and hitting his father's flail. When this happened for the umpteenth time, the father shouted, "You clumsy colossus, you're doing this on purpose, I'll beat you with the flail for it," and held the flail out to his son. He waited for nothing, struck the threshing floor with the flail and went away.... He didn't think where he was running until he found himself at the Bredůvka tavern, where the recruiters were looking for soldiers. Francek, with his head full of anger and defiance at his peasant's lot, did not hesitate and let himself be recruited.

Because he matched the requirements (age 17-40, height 168-180 cm), the recruiters welcomed him with open arms. His pocket jingled with some ten or fifteen gold coins, which the volunteers at the Frei Werbung were given as an advance, and his stomach warmed with the liquor which the officer frequently served him. "What do you want to hunch your back from morning till night, you can see the world with us, pretty girls everywhere...", rang in his ears. Perhaps in his annoyance he did not even realize that he was signing up for eternity (2).

He was wearing only a white coat and when he took the military oath, he may have regretted it a little. The barracks were filled with words that few recruits could really hear: "We swear to the Lord God Almighty by a bodily oath that to our most enlightened and powerful prince and lord Francis, King of Hungary and Bohemia, Archduke of the Alpine Lands, as the now regnant lord of the hereditary lands, and by his Royal Majesty to all the established lord generals and officers, who in His name will command us now and in the future, especially to our armourers, armour bearers and armour masters, and also to other superior and subordinate officers, we will be obedient, faithful and servile, honouring them and respectfully obeying their orders and commands faithfully, as well as making moves and keeping watch day and night, for and against the enemy in battle, in skirmishes and in all other occasions on land and water, wherever they may occur, and in whatever service their Royal Majesty may require, we, as valiant, valiant, and obedient, shall prove ourselves, as is fitting and proper for every honest and perfect soldier, according to those military articles confirmed by their Majesty in all their articles and covenants, as is fitting, to fight and contend with all the enemies of His Royal Majesty, without fail, always according to necessity, honestly, valiantly and courageously, and to have no correspondence or understanding with the enemy at all times, none of us to separate and withdraw from our regiment, company or fang, but to live and die. Whereunto grant us God Almighty and the holy gospel through Jesus Christ. Amen!" (3)

It is difficult to estimate how long he spent in training - several weeks or just a few days. It depended on the situation and the need at the time. The basis of everything was a step. The Austrian infantry moved in a marching column half a company wide, and speed of movement and manoeuvre was paramount. No one-two, but three kinds of step, which the recruits were taught over and over again... the ordinary (Ordinärschritt) - 95 steps per minute, the fast (Geschwindschritt) - 105 steps per minute, the double (Doublirschritt), extremely exhausting, used exceptionally to change formation and to attack - 120 steps per minute.

He endured the hard training with gritted teeth. The hooting and kicking soon ceased, for the officers soon learned that Francek was a smart and ambitious soldier. How could they not, when the uniform was warmer than the clothes of broadcloth, and the food was, after all, tastier than sour soup, peeling potatoes or buttermilk.... So the infantryman Franz Faltus trampled all over the empire, Bavaria, France, the emperor issued a document in Vienna on 15.2.1824, where it says: "We, Franz I, by the grace of God, Emperor of Austria .... acknowledge and note that Franz Faltus, lieutenant of the infantry regiment, in view of the merits he has gained, has been promoted to the status of nobility. He began as a common soldier, and after thirty years of voluntary military service, during which time he took part in thirteen field campaigns, during three of which sieges he served partly as a non-commissioned officer and partly as a real officer, he allowed himself to be used for other important military services to the satisfaction of his superiors. Therefore, as a reward for these services, we have elevated František Faltus, including his spousal descendants of both sexes, for all future times ... to the rank of nobility and bestowed on him the honorific title of "nobleman von" .... As a permanent proof of our will and elevation, we bestow upon František von Faltus the following emblem of nobility designed in colours, namely a red and blue shield converging exactly at the tip and half-way along its length, pointing towards the head of the emblem, which is supported by three heraldic flags, and above these in the centre of the shield's division a golden star floats, and to the right a crane in gold on green ground in a red field, and in a blue field a steep rock rises from the edge of the shield, and from it an armoured arm swears by a drawn sword with a golden hilt. "

Franz Edler von Faltus is listed in the "Militär-Schematismus des österreichischen Kaiserthums" from 1831 as a lieutenant (Oberlieutnant) of the 15th regular Halic (4) infantry regiment of Don Pedro, Emperor of Brasil. However, in popular usage the designation "Regiment Zach" persisted, after the previous owner. At the time Francis fled his home, Bohemia was the place of recruitment and the regiment was based in Chrudim. Therefore, it is quite logical that he ended up in its ranks.

If he became a member around 1794, he had a difficult time. The Imperial Appointment records thirteen campaigns in which he participated as a soldier. It is probable that he was in all the important battles against Napoleon's army - at Marengo, Ulm, at Austerlitz, at Lanshut. He was certainly not absent on 22 May 1809 at Aspern, where the French were first defeated. He might also have been at Wagram, at Dresden, in 1813 at Chlumec, and in mid-October of the same year at the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig, where half a million soldiers from all over Europe stood against each other. He was probably not absent from the last decisive battle with the French Emperor at Waterloo on 18 June 1815.

Two decades of gruelling campaigns, atrocities, looting, famine, defeats and victories. A time notched by tens of thousands of deaths. How many did a former Boer youth kill in the name of the Emperor?

His life went on... well, in a military way. Morning drill, evening revelry, drinking with his friends, and in the morning, with a sore head, drill again. They tried to convince each other that this was the best way to live. But time passed inexorably, and then came old age and illness. Old wounds from battles fought painfully reminded of the dead whom Francis had sent to the other world. He knew he would soon meet them. And there was no one to care.

"Since in this passing life nothing is certain but death, but its hour is uncertain... I, Peter Count Strozzi, lord of Horice... ordain that the aged poor officers and soldiers, who have become incapacitated in the service of war, from my estate and on it... be provided with food, drink, clothing and other necessities, so that they may live on it and not be forced to beg after their faithful and long service in war, or to fall into total ruin", wrote the count in his will on 3 August 1658. It was thanks to him and other patrons that small dormitories grew up at first, until finally in 1743 Empress Maria Theresa entrusted Count Stephen Kinsky with the administration of all care for Austrian military invalids. At first a large invalid asylum was established in Vienna, then in Prague, and a central invalid asylum was established for the Hungarians in Trnava. It was there that the childless František Edler von Faltus (5) ended up, and it was there that he died in February 1857.

As if his wasted life were not enough, before his death he wished his noble emblem to be taken to his home in Bořivava, where it was to serve as an encouragement to the young Hasidim.

The coat of arms together with all documents testifying to the military service of František Faltus and his merits during the field campaigns reached Bořitava No. 19 in September 1859 through the district office in Žamberk.

The Bořitava neighbours decided to paint the coat of arms on a wooden plaque, to organise a celebration and to attach the coat of arms to the family house during the celebration. The date of the festival was set for 8 October 1877. On that day, however, it had been snowing heavily since the morning. A new date for the festival was set for the following spring, namely Sunday 12 May 1878.

(1) Antonín Špinler, Lidé od Orlice, Oftis 2004

(2) Lifetime military service was changed to 10-14 years on 2 February 1802.

(3) the text of the military oath of 1805 (taken from the book SCHILDBERGER, Vlastimil. The Imperial Army, the Campaign of 1805 and the Battle of Austerlitz. Brno, 1998, pp. 11-12)

(4) according to the place of supplementary conscription

(5) Franz Edler von Faltus also wrote a slim, strangely enough not military book Ausflüge von Wien nach Maria Zell in Steiermark und seine schönsten Umgebungen of 51 pages, which was published in Vienna in 1842 by Carl Überreuter.

The Styrian State Library also has an extremely rare series of large lithographic views of the Mürztal by Franz Edler von Faltus, circa 1840.

translated by Deepl Translate

Myslím, že rytíř Faltus byl sám se sebou spokojený. Kam to, panečku, dotáhl... Za vzor se dával upřímně.

Každý si projektujeme, jaký že velký smysl má ten náš konkrétní život. Přitom subjektivní hodnocení často neodpovídá tomu objektivnímu. Esesáci v koncentračních táborech byli také ve většině přípdů přesvědčeni, že konají dobro pro lidstvo...