On our way home from a trip to Boston last summer, we stopped in Providence, Rhode Island, the former home of one Howard Philips Lovecraft. Now that his literary legacy is a largish business, the city has adopted him, and NecronomiCon, "the international festival of weird fiction, art, and academia," named for a fictional book of esoteric lore that Lovecraft referred to in his stories but never actually wrote, returned there for its 2017 meeting. We were a couple of weeks too early, dang it.

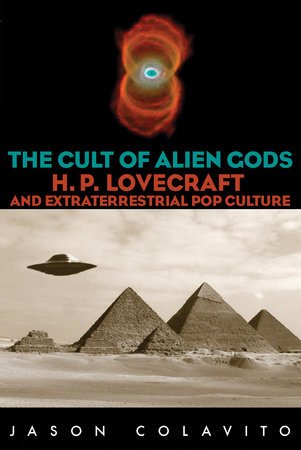

However, at a downtown bookstore I found this:

Jason Colavito is a freelance writer and professional skeptic. He focuses especially on debunking archaeology. This book was published in 2005, which means that he was following the “ancient aliens” thing long before I stumbled into the subculture at a Graham Hancock lecture in 2013. I cited Colavito's website in the IGMS column I wrote about that experience, called "Mistakes Experiments of the Gods."

Colavito's thesis is that consciously or unconsciously, every one of the “ancient aliens” authors was using concepts derived from HP Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos, an early experiment in shared world-building. If you're unfamiliar with HPL, he was a pulp writer whose vision of cosmic nihilism has now influenced five generations of science fiction and horror creators, everybody from Robert E Howard (who knew and corresponded with him) to Ramsey Campbell in prose, to Mike Mignola and Alan Moore in comics, to HR Giger in the visual arts and Guillermo del Toro in the movies.

Sketch by HPL of his most famous creation, the alien cephalopod god-monster Cthulhu.

He had a thing for tentacles, which show up everywhere in pop culture now – but so did HG Wells a generation earlier (War of the Worlds, 1906 edition), so that doesn't by itself prove anything. The thing is, most of these artists are happy to claim HPL as a literary ancestor, despite his racist attitudes. It helps to establish their own nerd cred. Those writing “non-fiction” want nothing to do with him, however, so Colavito set out to make the case for himself.

The Book

Despite the subtitle, HP Lovecraft and Extraterrestrial Pop Culture, Colavito stays mostly with such so-called nonfiction. He has a chapter “Science and Pseudoscience in Lovecraft's Time,” and one on “Science Fiction and Horror Before Lovecraft.” After that, except for one chapter on 50s and 60s people like Rod Serling, and a few mentions of the Star Trek and the Stargate franchises, this is not really a book about genre SF. What Colavito does instead is to follow one meme-line through more than a century of popular books. Here's a timeline sketch:

- Ignatius Donnelly's Atlantis: the Antideluvian World (1882)

- Helena Blavatsky's The Secret Doctrine (1888)

- W. Scott Elliot's The Story of Atlantis and Lost Lemuria (1896)

- James Churchward's The Lost Continent of Mu (1926)

- Lovecraft's “The Call of Cthulhu” (1926)

- Pauwles & Bergier's Les Matins de Megiciens (1960), translated as Morning of the Magicians (1964)

This book is really the linchpin of Colavito's argument. Bergier was an avowed fan of Lovecraft's fiction, and the pair ran a French SF magazine called Planete.

- Robert Charroux's various books in French

- Erich von Daniken's Chariots of the Gods?(1971, at least in the US)

- Robert Temple's The Sirius Mystery (1976)

- Bauval & Gilbert's The Orion Mystery (1994)

- Graham Hancock's Fingerprints of the Gods (1995)

Colavito ends with the creepy as hell realization that at least some of the restrictions on human cloning and stem cell research in the US are due to a publicity stunt where Brigitte Boisellier, a chemist member (now leader) of the Raelian Revolution, publicly claimed to have cloned a human being -- a little girl called Eve (of course) who was living in secret with a family in an undisclosed country. And all this time, I thought the people who wrote Orphan Black were being creative! Their "Neolution" cult is pretty clearly a reference.

#CloneClub on Twitter [image link to BBC]

It's a pretty good book, but necessarily incomplete.

Charles Fort is mentioned like five times. More to the point, there's a whole other strand of ancient civilization lore, based not on sunken continents or space, but on caverns and the Hollow Earth hypothesis. In The Man from Mars, Fred Nadis follows the career of superfan and magazine editor Ray Palmer, who published an influential and profitable series of “Shaver mysteries,” about the evil race of Deros, who lived below the ground and aimed their thought-disrupting rays at us poor surface dwellers to drive us to crime and corruption and war. Richard Shaver was a possibly schizophrenic artist who liked to cut open rocks with a saw and used the images he found inside as inspiration for his stories, which Palmer consistently labeled as true, except when it was more convenient to label them as fiction. I enjoyed that book more than Colavito's book, at least partly because Nadis seems to have more sincere appreciation for Palmer's Trickster cleverness.

MEET RAY PALMER, hustler, trickster, and visionary—a hunchbacked man, just over four and a half feet tall, who nevertheless was an indomitable force, the ruler of his own bizarre sector of the universe. Armed with a sharp intellect and incredible drive, Palmer chose to apply his brilliant mind in unusual directions—oftentimes enchanting us with sagas of worlds and beings that no one before knew existed. He was a charismatic writer, editor, and publisher of science fiction, fantasy, and supernatural pulp journals, and with his typewriter, he changed the universe as we know it. Palmer was a visionary trendsetter who created one sensation after another. He jumpstarted the flying saucer craze; he broke a story, followed by hundreds of thousands of Americans, describing evil denizens of the “inner earth”; he reported on cover-ups involving extraterrestrials, the paranormal, and secret government agencies decades before the X-Files. In a career full of paradoxes, peers praised him for being the editor that made Amazing Storiesthe all-time best-selling science fiction magazine, and denounced him as “the man who killed science fiction.” He invented a multitude of alluring and weird publications, among them: Other Worlds, Imagination, Fate, Mystic, Search, Flying Saucers, Hidden World, Space Age, and Forum. Love him or hate him—and many did both—Palmer had boundless energy that would not be denied, perhaps not even by death itself: he pictured heaven as a place where he could keep doing what he liked best, which was running a printing press and spinning tales of unusual phenomena, strange creatures, and even stranger lands. This is the story of an offbeat Midwesterner who fulfilled his own singular dream—a character named Ray Palmer who just may prove to be the oddest, most intriguing man you’ve ever met.

Those subterranean mysteries have at times cross-pollinated with the alien astronaut stories, as in the work of South African author Michael Tellinger, who is all over YouTube talking about the miles of tunnels and caverns left behind by gold-mining aliens. He also has a thing for giants.

I fully agree with Colavito, however, about the underlying social dynamics of the ancient aliens phenomenon. He sees these authors as revolutionaries, Old Testament-style prophets who are pushing back against the economic industrial machine system that has captured the human imagination, replacing the truer, more democratic practices of inquiry: science and history and religion. I made a similar argument about David Wilcock, who I called an accidental shaman, in this post from last year. It's ironic, then, that the tone of Colavito's book is often like that of Skeptic Magazine – a little snarky, a little morally superior. That's a minor point, though. It's a good book, and I learned a lot by reading it.

H.P. Lovecraft was always on the periphery of my literary to-do list, but I only got around to reading some his works last year. I do quite enjoy his weird horror, the unsettling creativity of the Cthulu Mythos is fantastic, and his influence is clear throughout horror and sci-fi today, particlualry in the Hellboy comics which I also started reading and absolutely adore. But questions of the man's pronounced racism are hard to ignore...

Recently was put onto Thomas Ligotti, whose works follow the same vein of eldritch horror, but apparently far more "thoughtful and compelling" and without the bigotry of HPL (according to Kris Straub, at least). Looking forward to giving him a read.

I've not read Ligotti, and am not really a horror fan in general, though I do like Hellboy. Probably the last horror I really enjoyed was The Sub, part of Thomas Disch's Supernatural Minnesota series. Black magic and black humor in roughly equal parts.

http://beatrice.com/wordpress/2010/11/14/read-this-thomas-disch-supernatural-minnesota/