I analyse a tract of the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer, and explore why medieval practitioners of natural science, or alchemy, fell into disrepute.

Geoffrey Chaucer

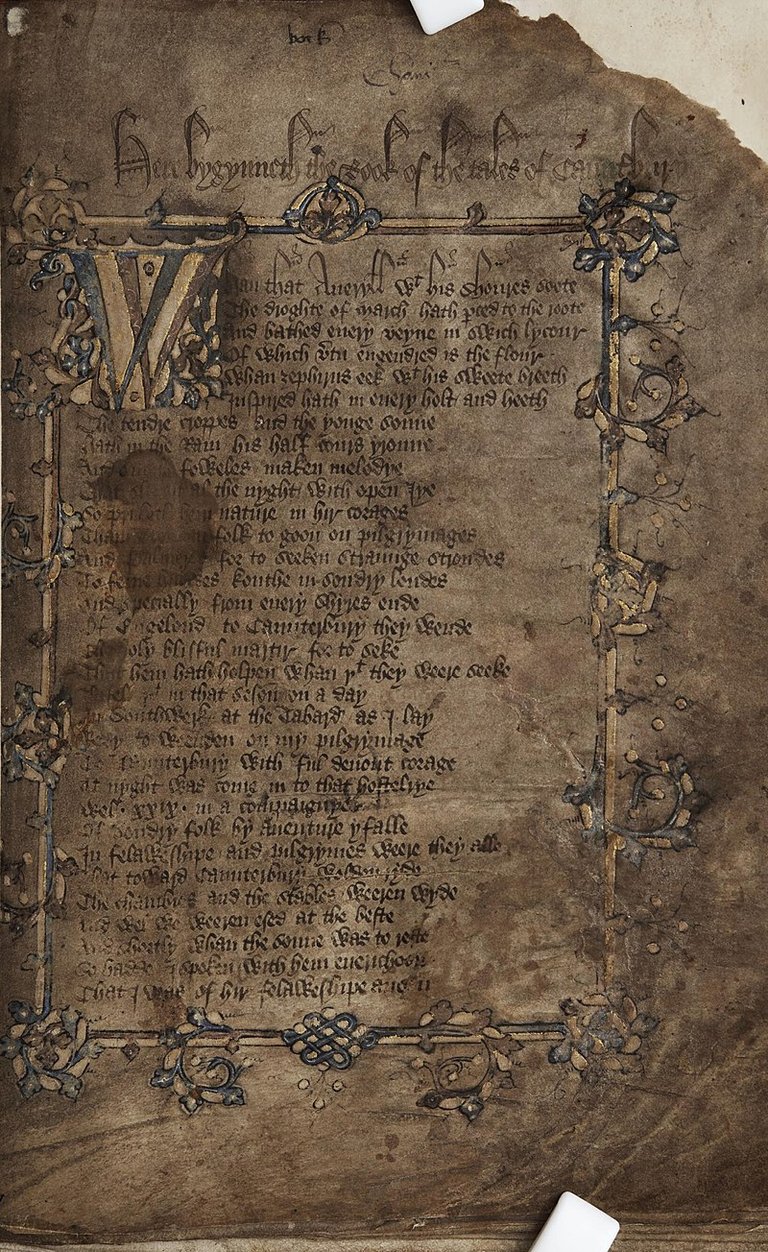

The Canterbury Tales was published after Geoffrey Chaucer's death in 1400. It is structured about a group of travelers on a pilgrimage to Canterbury Cathedral. Every night as they sit about the fire of whatever inn they stay in, one of the group tells a tale to the others. The entire gamut of medieval professions is represented by the characters in the book; a Knight, Miller, Reeve, Shipman, Physician, and a succession of clerics, monks and nuns. The character (and tale) that I find the most interesting is that of the Canon's Yeoman - or servant.

The Canon's Yeoman's Tale

In the prologue to the tale, the Host asks the Yeoman why, if his master (the Canon) is truly so sagacious, then why is he, the Canon, dressed in gaberdine that is hardly worth a mite, torn to bits and isn't even clean. The Yeoman hints darkly that what the Canon works at can never be successful. The Canon, he tells them, is clever enough to understand his esoteric craft, but not enough to know how to make it succeed. The Yeoman doesn't want to say any more, but the Host slowly teases more details out of him. The Yeoman and the Canon live in slums, fear-stricken and secret places /where those reside who dare not show their faces. The Yeoman's own face is discoloured from blowing up the fire. He and the Canon keep borrowing money, say a pound or two, on the pretext that their lendors' capital will be increased. But the Yeoman is not optimistic. It will make beggars of us all, at last, he says.

Debt and Despair

The Yeoman then warns the gathered company against the debt, despair and ruin that practising the craft has brought him. He names the substances we worked upon, among them silver, orpiment, burnt bones and iron filings, ground into finest powder and poured into an earthen pot, followed by salt and pepper, and covered by a sheet of glass. At this point, I wondered if Chaucer was not indulging in a medieval leg-pull, rather than rendering an authentic account of the chemistry of the time. Tradition has it that he had sometime practised the "esoteric craft", in addition to being a poet, soldier, knight and Justice of the Peace.

Chaucer and the Secret

The poem is, of course, a window into the mind of Chaucer and a probe of the depth of his knowledge. I doubt, however, if Chaucer was ever a serious practitioner of alchemy. Quite likely, when he gained entrance to its heremetic world, he was just researching a book. The odder substances mentioned by the Yeoman, the least of which are the salt and pepper, are likely thrown in for comic effect - or just to trip up the would-be practitioner with. After all, if Chaucer really did know "the secret", he was hardly going to give it away. No matter his agenda, there is enough evidence to demonstrate that the fourteenth-century alchemist was actually a proto chemist. For example, the Canon's Yeoman lists orpiment among his roll-call of substances.

Beauty, Poison and Arrogance

Orpiment, or sulphide of arsenic, made a beautiful yellow paint in illuminated manuscripts, but is too poisonous for contemporary use. If the spin-off products of alchemy were of use to painters and other artisans of the time, how did a useful profession fall into disrepute? When Chaucer's Yeoman is finished describing the Canon, he goes on to tell his tale, that of a chantry priest who is deceived entirely by an out-and-out scoundrel of an alchemist. Seemingly, Chaucer had issues with the profession, too. By the 1400s, the practice had been outlawed by the church. According to John Gage, this was because of the alchemists' arrogance, their obsession with precious metals, and their cloaking their craft in secrecy and obscure terminology – what Gage called the spiritualization of alchemy.

Miscreant or Mystic?

By the late 1500s, the alchemist still featured in fiction. In Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet, Romeo buys a poison from a broken-down alchemist who protests that he could hang for doing so. Romeo points out that the unfortunate wretch is going to die of starvation anyway unless he, the alchemist, accepts Romeo's money. Later on, when the play has reached its heartbreaking conclusion, we hear the alchemist is going to be punished. Interestingly, herbalist Friar Laurence is to be pardoned for giving Juliet the sleeping potion - a comment on the status of both practitioners. But out of the crucible of persecution and superstition, the modern chemist, distinct from the miscreant and the mystic, was born. However, I suspect that even the earnest, hard-working, proto chemist toiled with gold pieces rather than the betterment of mankind, in his imagination. Whatever, I do urge you to read the wonderful snapshot of medieval England that is Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales.

Sources

Colour and Culture: Practice and Meaning From Antiquity to Abstraction by John Gage, Thames and Hudson, London, 1993.

The Painter's Methods and Materials by AP Laurie, Dover Publications, New York, 1988.

The Canterbury Tales, by Geoffrey Chaucer, Penguin Books, London, 1951.

Posted using Partiko Android

Peace, Abundance, and Liberty Network (PALnet) Discord Channel. It's a completely public and open space to all members of the Steemit community who voluntarily choose to be there.Congratulations! This post has been upvoted from the communal account, @minnowsupport, by evariste from the Minnow Support Project. It's a witness project run by aggroed, ausbitbank, teamsteem, someguy123, neoxian, followbtcnews, and netuoso. The goal is to help Steemit grow by supporting Minnows. Please find us at the

If you would like to delegate to the Minnow Support Project you can do so by clicking on the following links: 50SP, 100SP, 250SP, 500SP, 1000SP, 5000SP.

Be sure to leave at least 50SP undelegated on your account.