I’ve already written two posts on this topic: Blockchain Governance: A Dilemma and Solving the Blockchain Governance Dilemma. I highly encourage that you read those before you read this one, as they will provide context for this article. The following intro is taken from Solving the Blockchain Governance Dilemma.

Empowered by blockchain and DLT (Distributed Ledger Technology), we now have the opportunity to shape the governance, incentives, and ecosystem of our future through programming decentralized forms of governance.

There are two main properties of any governance scheme:

Incentives. In any system, people have incentives. But these incentives are almost never fully aligned. To build a successful governance system, actors’ incentives should be aligned as close as possible for the good of the network.

Mechanisms for Coordination. But incentives are almost never 100% aligned, so all parties need to find a way to communicate and coordinate based on their common incentives. A major factor is how much of the decision making can be done on-chain versus off-chain, with on-chain usually being the easier route for coordination, but harder to program.

And a bit of terminology that I will use for this article:

- Stake-weighted: When one address doesn’t equal one vote, where one coin equals one vote.

- Prediction market: A betting market. This is useful not only for betting, but because we can see what people think is going to happen based on what they bet on. But if they say something that they don’t actually think will happen, they will probably lose their bet, creating an incentive to provide what they think will happen, not what they necessarily want people to think will happen.

- Supermajority: While a majority means a >50% majority, a supermajority means a >66% majority.

In the previous post I talked about already implemented methods of blockchain governance, and so, logically, in this one I will talk about proposed but not yet implemented methods of blockchain governance. All of these will be on-chain, because it is much more interesting to talk about and most likely the way blockchains will govern themselves in the future.

One thing to note, though, is that on-chain governance might not be right for every blockchain. While on-chain governance is usually more transparent and decentralized, the fact that it is hard-written in code can be a problem. You can game code a lot more easily than off-chain interactions. It might be best for protocols that want to stay safe and don’t need to change a lot, like Bitcoin, to use off-chain governance instead of on-chain methods, while coins that want to ‘move fast and break things,’ like Steem, might want to use on-chain governance so that they can be more flexible, transparent, and decentralized.

Tezos

Tezos is a blockchain on-chain governance solution that raised over 200 million USD in its token sale. Governance works by a developer creating a proposal for a code/protocol change, with all the users voting either for or against the change in a stake-weighted vote. If there is a majority of stake voting against the proposal, then the proposal will not go through. If there is a majority of stake voting for the proposal, then a testnet will be created where the protocol/code change will be tested for 1 week. After the results of the week on a testnet have been seen, then a confirmation vote will occur, also stake-weighted. If the majority of stake votes against the change, then the proposal will not go through, but if a majority of stake votes for the change, then the proposal will go through. If the proposal goes through, a few Tezos will be minted and given to the developer who created the proposal.

This scheme is very powerful, because it shifts control from the validators to the users. But it is very possible that Tezos could suffer from a lack of voter knowledge or a lack of voter participation. The DAO lacked participation from users, with only a very small percentage of stake voting for proposals, and there is no reason that Tezos would not suffer from the same problem. Another problem is the fact that it might be difficult for the average user to dedicate the time and energy to voting for proposals and that they might not understand the full implications of a proposed protocol change.

DFINITY

DFINITY uses a system that allows on-chain votes to a change in the protocol like Tezos and the ability to rollback previous transactions. Users will be able to participate in a stake-weighted vote on whether to remove or edit the ledger in the case of an undesirable incident, for example, a hack or a marketplace selling drugs on the blockchain. While this would be very useful for policing transactions on the blockchain, it would also allow for direct censorship and people’s tokens to be taken. But, on the flip side, what if the Etherum DAO hack could have been reversed with a simple vote? It would have stopped Ethereum classic from happening, remove a lot of the drama attached to the hack, and be so much simpler.

Of course, the ability to directly censor transactions and take coins away from users should not be taken lightly. Maybe certain changes would not just require a majority, but require a supermajority to pass.

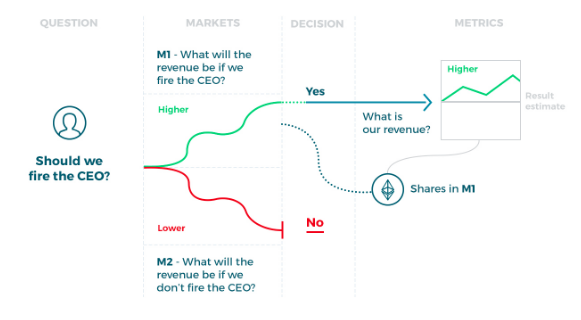

Futarchy

Futarchy is a governance method that has not been tested yet, but has a lot of potential. Society defines its values, and every year the progress on those values is tracked. They could be user welfare, a company’s revenue, or even the value of the cryptocurrency. Then, when a proposal is created, a prediction market starts where people bet on how much progress for the values will be accomplished if the proposal is passed. The general sentiment of this prediction market is then taken: if the prediction market shows that passing the proposal will bring the organization closer to reaching its values than not passing it, then the proposal will be passed, and if the prediction market shows that not passing the proposal will bring the organization closer to reaching its values than passing it, then the proposal will be rejected. Finally, once we see what the progress is on the organization’s values after the proposal is passed or rejected, the bets will be paid out to those who predicted the best.

One idea for a ‘value’ is that every year, every user is asked a simple question: “Rate your satisfaction with your year on the blockchain from 0 to 1.” Then a stake-weighted average is taken of all these ‘welfare scores’ to find the overall ‘welfare score,’ what the blockchain is trying to maximize.

In futarchy, the average user doesn’t need to understand the complex proposals, they just have to either provide data to help judge progress on values (like in the welfare score example), or literally nothing (as in the version where the values are to increase revenue). The only people who need to read complex and technical proposals and understand their implications are betters, who are penalized for ignorance and being incorrect.Futarchy seems like a great idea, but there is lots that could go wrong, and implementing it is difficult. We’ll have to see how well it does in the future.

Coins mentioned in post:

fyi, you might be interested in another new voting method that has primise as well, with some detailed academic analysis - http://ericposner.com/quadratic-voting/