Bitcoin Denial of Service Vulnerability Found in the Code

Introduction

Today, on September, 18th, 2018, there was a ‘vulnerability’ in the Bitcoin client (specifically versions 0.14.0 and 0.16.2) that were identified by an anonymous reporter via Bitcoin Core’s main repository.

There has since been a fix that was released formally by Pierre Rochard, a developer (?) on the Core team.

According to the documentation of the fix, posted in the GitHub cited above,

“A denial-of-service vulnerability (CVE-2018–17144) exploitable by miners has been discovered in Bitcoin Core versions 0.14.0 up to 0.16.2. It is recommended to upgrade any of the vulnerable versions to 0.16.3 as soon as possible.”

Description of the Issue

The issue, which was exposed to a greater audience via a Reddit post, appears be borne from a flaw in the compilation of transaction data on the protocol.

Specifically, this mailchimp newsletter, referenced in the Pierre Rochard pull request, covers the issue in greater depth.

In the newsletter, it states:

“ Upgrade to Bitcoin Core 0.16.3 to fix denial-of-service vulnerability: a bug introduced in Bitcoin Core 0.14.0 and affecting all subsequent versions through to 0.16.2 will cause Bitcoin Core to crash when attempting to validate a block containing a transaction that attempts to spend the same input twice. Such blocks would be invalid and so can only be created by miners willing to lose the allowed income from having created a block (at least 12.5 XBT or $80,000 USD).”

Herein lies the vulnerability, as described above.

While it may seem insignificant at face value, it could actually cause considerable issues on the network.

Before explaining some of the issues that it could cause, its best to first make sure that we’re caught up to speed on what a Denial of Service attack is and what it means in the context of blockchain, specifically Bitcoin.

What is a Denial of Service Attack?

According to us-cert.gov,

“ A denial-of-service (DoS) attack occurs when legitimate users are unable to access information systems, devices, or other network resources due to the actions of a malicious cyber threat actor. Services affected may include email, websites, online accounts (e.g., banking), or other services that rely on the affected computer or network. A denial-of-service is accomplished by flooding the targeted host or network with traffic until the target cannot respond or simply crashes, preventing access for legitimate users. DoS attacks can cost an organization both time and money while their resources and services are inaccessible.”

What’s stated above is a bit of a mouthful, but it does accurately describe what a Denial of Service tends to be.

Now, in the context of blockchain, since it is a decentralized protocol, a denial of service attack is not the exact equivalent in this case (typically, it renders a network inaccessible), but the fundamental principle is the same.

One of Satoshi’s Main Concerns was Preventing DoS Attacks on Bitcoin

In order to assess the impact of a DoS attack on Bitcoin, we need not look any further than at the forum posts posted by Satoshi Nakamoto himself.

Where is the separate discussion devoted to possible Bitcoin weaknesses.

Where is the separate discussion devoted to possible Bitcoin weaknesses.bitcointalk.org

In the conversation cited above, Satoshi admitted that he/she/they were musing the possibility of adding a PoW operation to transactions in order to ensure their validity and prevent a DoS attack via a flood of inaccurate transactions.

The greater alternative that was decided upon by Satoshi was to just create a fee market while giving miners the option to only mine transactions that contained the greatest fees.

The logic behind this decision was that, if the mempool became clogged with illicit/fraudulent transactions, then users would be able to ‘bid’ with other users to have their transactions mined by applying a fee to the network (which miners would receive for successfully mining a block that included said transactions).

By doing so, Satoshi reasoned that this would undermine a DoS attack by simply allowing the legitimate actors (on the user-facing end) to get their transactions confirmed without delay by simply offering a higher fee to the miners for mining their transaction. In such a situation, an attacker would need to outbid the majority of legitimate actors on the protocol in order to ensure that they accomplished their mission, because their transactions would be reviewed first before the others, thus creating a lull in the chain.

Assessing Satoshi’s Fee Model Method for Preventing DoS Attacks

While Satoshi’s method of preventing DoS attacks is not bullet proof and there were tertiary consequences to its implementation that were not felt until years later (i.e., the 1 MB block limit being hit, resulting in an excess amount of TXs in the mempool, which spiked the fee rate on the protocol exponentially), it still proves to be the most effective and least invasive means of preventing a DoS attack. And, the core philosophy (pun intended), mirrors Satoshi’s to the extent that security has been considered paramount to the efficiency of the chain itself.

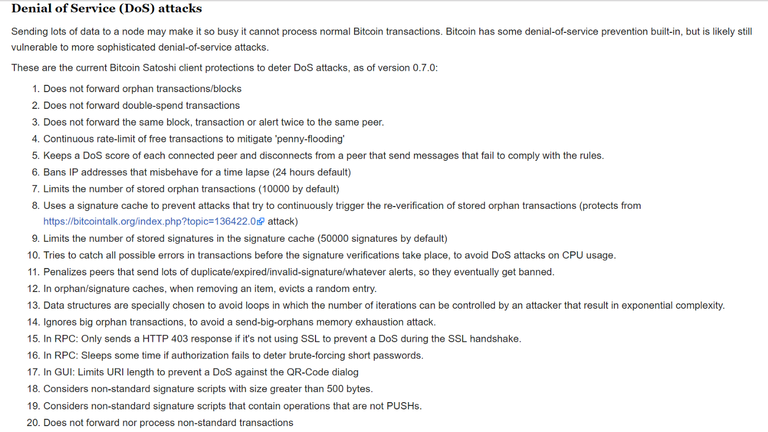

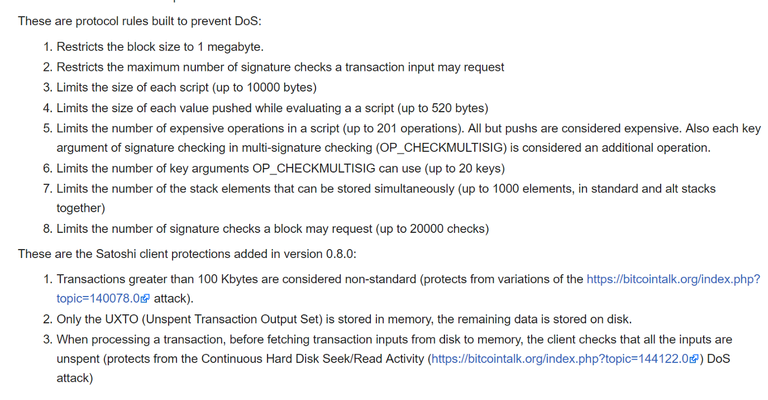

Here are some of the implementations of DoS-prevention measures on Bitcoin:

Source: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Weaknesses#Denial_of_Service_.28DoS.29_attacks

Potential Threats in the [Patched] DoS Susceptibility in Older Bitcoin Client Versions (0.16.2 & 0.14)

Based on what we know, the obvious threat comes from the fact that invalid transactions being mined would result in the failure of nodes on the above listed clients.

This means that the attack vector inherent in this incident would stem from a miner mining an invalid block purposefully, which would be a waste of the resources that are necessary to fulfill the Proof of Work as well as the forfeited block reward (12.5 BTC at the time of writing). However, they would succeed in knocking out a number of nodes on the network, which could then open the network up to more nefarious attacks.

A full node is not necessary for mining, but it is rare that any mining operations would be running on the protocol without one, since it is helpful to know when a block has been propagated to the network. It is also not entirely uncommon that an incorrect block could be propagated to the network.

Conclusion

After review of the issue and the subsequent fix, it appears that the issue itself is under control.

As to how the issue itself manifested in the code of Bitcoin Core is a question that remains unanswered at this point in time, but the important thing for Bitcoin users is that it has been fixed.

Again, more information can be found in the links posted throughout this piece.