JOURNAL OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS

A THINKING AID

B. F. SKINNER

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

Writing a paper is often a process of discovering what you have to say. A small, inexpensive, "threedimensional" outline of the paper is a help in guiding the process of discovery. New points can be accurately placed as they appear. The outline grows with the paper. The construction of such an outline is described. DESCRIPTORS: old age, verbal behavior, thinking, work output

I used to say that I wrote and rewrote a paragraph until I could "think it all at once." At times I have felt that I could think a whole paper or chapter of a book all at once. After finishing Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971), I took a short vacation during which, without the manuscript, I wrote short summaries of the chapters. When I  hapter all at once." That could not have been literally true, of course, but I had organized the material so tightly that I moved effortlessly from one part to another as I thought it. Something of the sort seems to happen in the shaping of complex behavior, as in figure skating, for example, or in responding to very complex presentations, as in becoming familiar with a book, painting, or piece ofmusic. The first time we read, say, The Brothers Karamazov, it consists of a sequence ofepisodes. After reading it several times we "know the book" in a different way. We see how its parts relate to each other and how consistently the characters behave. Dostoevsky himself, going over the manuscript many times, must have "thought it all at once" in a very special way. When we first see such a picture as Picasso's Guernica, it is little more than a collection of parts. As we become familiar with it, we see it as an organized whole. When we first hear a symphony it is a sequence of parts, but as we become familiar with it, one part leads easily to another, variations reveal

hapter all at once." That could not have been literally true, of course, but I had organized the material so tightly that I moved effortlessly from one part to another as I thought it. Something of the sort seems to happen in the shaping of complex behavior, as in figure skating, for example, or in responding to very complex presentations, as in becoming familiar with a book, painting, or piece ofmusic. The first time we read, say, The Brothers Karamazov, it consists of a sequence ofepisodes. After reading it several times we "know the book" in a different way. We see how its parts relate to each other and how consistently the characters behave. Dostoevsky himself, going over the manuscript many times, must have "thought it all at once" in a very special way. When we first see such a picture as Picasso's Guernica, it is little more than a collection of parts. As we become familiar with it, we see it as an organized whole. When we first hear a symphony it is a sequence of parts, but as we become familiar with it, one part leads easily to another, variations reveal

Reprints may be obtained from B. F. Skinner, Department of Psychology, William James Hall, 33 Kirkland Street, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138.

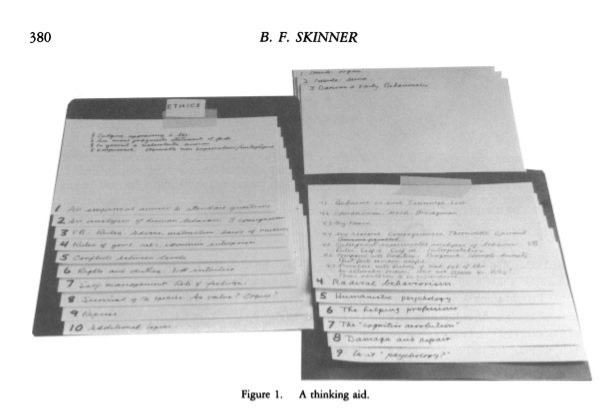

their common themes, and we eventually think of it as some kind of single thing. Recently, when writing a paper, I felt that I was taking too much time to reach the point at which I could "think a paragraph," let alone a whole paper, at once. Age was no doubt relevant. Old people forgetthings much more quickly than young people do. In moving from one part of a paper to another, might I not be carrying too little ofit with me and hence not accumulating as much of it as a whole as I once did? I decided that something must be done, and I built several prosthetic devices, which have worked so well that I wish I had had them when I was younger. Two ofthem are shown in Figure 1. I begin with a plastic panel-one side cut from a three-ring binder, for example. I fasten cards (5 by 8 in.) on the panel, using short strips ofmasking tape as hinges. I put the first card at the lower right-hand corner of the panel with the red line near the bottom, and add tape at the top edge. The hinge holds thecard more securely ifa ballpoint pen is run firmly along the tape at the edge of the card. I put a second card slightly to the left, with its lower edge on the red line of the first. Eight or ten cards reach the left-hand edge of the panel. I number the cards with a bold black pen and enter descriptive tides on the exposed edges. When the cards are opened, as in the panel at the right, numbers and titles are also entered along the exposed edges. I bend the lower left-hand corner of each card slightly upward so that a fingernail lifts it easily. Before beginning a paper, I have usually collected notes, clippings, references, and other ma

379

1987,20,379-380 NUMBER4 (WINTER 1987)

380 B. F. SKINNER

.- 9

F 1 t n

Figure 1. A thinking aid.

terials. I group these in sections and put the sections in some kind oforder. I give each section a number and assign it to a card. I enter subdivisions on each section of the rest of the card and number them decimally. As new material turns up, it is easy to find a place for it on the appropriate card. When a card becomes crowded I remove it (peeling the tape from the panel) and put a fresh one in its place. As better orders appear, I rearrange the cards. When I sit down to work on a paper in progress, I first read the exposed entries-a matter of a few seconds. If that is not enough to give me a "feel" ofthe paper, I read some ofthe cards. As the paper develops, it becomes obvious that gaps need to be filled, that some sequiturs are non, that some parts are in the wrong place, that some parts are in the wrong paper, that some parts are too briefand need to be lengthened and others too long and need to be shortened. In this way I keep the paper, not "in mind," but in front of me as a complex object on which I am at work. Most of this can be done before writing a sentence but, ofcourse, sentences begin to appear, and sections are written. I collect them in a ring binder with dividers corresponding to the cards on the

panel. I do not write the paper from beginning to end; I work on any part of it that happens to be especially interesting at the time. Slowly the paper comes into existence. I could not have predicted any of it when I started to write. I began with an assigned subject matter, of course, and something of what other writers had said about it may have been important, but the thinking aid has given my verbal and nonverbal histories the best chance to make themselves felt. The paper has evolved. In that sense I have discovered what I had to say (Skinner, 1981). Something of the sort can be done with a computer, of course, but the panel is easier to slip into a briefcase or carry to the breakfast table or an easy chair.

REFERENCES

Skinner, B. F. (1971). Beyondfreedom and dignity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Skinner, B. F. (1981). How to discover what you have to say. The Behavior Analyst, 4, 1-7. Reprinted in Upon further reflection. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Received May 19, 1987 Final acceptance July 6, 1987 Action Editor, Jon S. Bailey

Sort: Trending