Arnold Böcklin (1827–1901) belongs to one of the most lambasted painters in art history. The early modernists considered him as theatrical and comical. Today we view his art with different eyes.

Few artists have encountered fiercer storms in the art climate than the Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin. In the 1890s he was regarded as the leading symbolist in Germany. And at the turn of the century, for many Nordic artists and writers - such as Edward Munch and August Strindberg - he was something of a cult figure. The decline came quickly parallel with the emergence of modernism. Already at the outbreak of World War I, Böcklin was almost forgotten. His mythological and pessimistically civilization-critical art was seen as something antiquated. Böcklin's art was considered to represent all the things that French-oriented European modernism wanted to break free from. The advocates of modernism considered his paintings to be thought and not seen, artificial rather than reality-based.

The attack against Böcklin was led by the Jewish art critic Julius Meier-Graefe, who in his 1905 pamphlet "Der Fall Böcklin und die Lehre von den Einheiten" exposed Böcklin's art to a reckless treatment. A critique that contained virtually all the pejoratives that would later be included in the rhetorical arsenal of modernism and repeated ad nauseam the coming half-century by modernist theorists.

Böcklin's art was accused of being an impure mixture of literature, theater and visual arts. It was non-autonomous and illustrative, subject to various non painterly aspects. According to Meier-Graefe, Böcklin's paintings were poorly cohesive, and they weren't a harmonious unity but rather constructed of poorly integrated elements in conflict with each other. Böcklin's colors were characterized as raw and brutal and his forms as clumsy and even unintentionally comic. His images, according to Meier-Graefe, were not art, but overloaded and bombastic kitsch.

The criticism of Böcklin was not limited to the aesthetic. It had several other entries: political, existential and psychological. Böcklin was considered to represent an unhealthy Germanness. "The case of Böcklin, is the case Germany," Meier-Graefe wrote. It obviously didn't help that Hitler happened to admire Böcklin.

While modernism was future-oriented and optimistic, Böcklin's allegorical "Gedankenmalerei" (thought-painting) was filled with elegiac melancholy, far from any future perspective. His "Ruin by the Sea" (1881) is a Late Romantic, obscure vision of downfall. In many of his paintings there is a mood of transience, decay and resignation. Generally, the older Böcklin became, the darker his paintings became. There's not much peace, but all the more of battle, struggle, desolation, pain, anxiety, fear, destruction and death. "Battle of the Centuries" depicts a kind of mythological primal battle. The gloomy subject matters can be attributed to the fact that he led a troubled life, plagued by poverty and that cholera and typhoid was a constant threat to his family (he lost 8 of his 14 children), but also that the spirit of the time was generally pessimistic.

When surrealists such as Max Ernst and de Chirico rediscovered Böcklin after his death, they particularly noted the extraordinary creativity of the painter, his iconographic innovations, his profound and iconoclastic interpretation of mythology and the erotic and morbid atmosphere of many of the paintings.

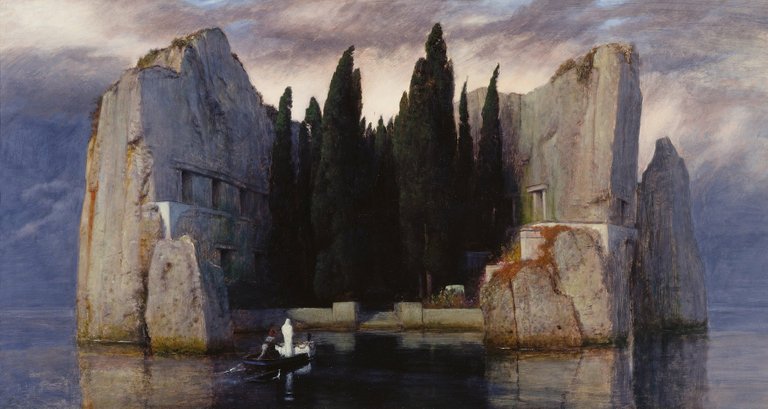

Böcklin's undisputedly most famous painting is "Isle of the Dead", a truly iconic image that has rooted deeply in the Western consciousness. Arnold Böcklin made five versions of "Isle of the Dead" between 1880 and 1886. The paintings were immensely popular in the decades around the turn of the century, and they inspired countless of poets, artists, play writers and composers, including Sergei Rachmaninov who wrote a symphonic poem of the same title in 1909. "Isle of the Dead" became a death monument over the century and a symbol of the weltschmerz of the fin de siècle.

The painting depicts a deserted rocky island in the middle of a black sea. A small rowboat approaches a little harbor. In the boat we see an oarsman and a figure wrapped in what looks like a white burial shroud, standing in front of a coffin. The oars glide through glassy, still and unfathomable depths. Within the colossal, anemic rock, lies the secret of eternity. Cypresses grow on the island, trees that especially in southern Europe are associated with cemeteries, and in the cliffs there are portals and windows, gaping oblong holes that suggest that tombs have been chiseled out. There is no wind to rustle the dark shroud of cypress leaves. The island's crescent shape opens up towards the viewer. The entrance is obscure, much like they used to paint female genitals at the turn of the century. It's as if the painting evokes a mating act between the viewer, death and silence. Many have interpreted the man at the oars to be Charon, the ferryman of Hades who carries souls of the newly deceased across the rivers Styx and Acheron. However, Böcklin himself gave no clues - it was not even him who gave the series of paintings its title.

A common and very likely explanation is that Böcklin was inspired by the English cemetery in Florence. His studio was nearby and one of his own children was buried there. The cemetery certainly has its fair share of cypresses and monuments, but the fact remains that it's not an island. It's therefore easy to assume that Böcklin was inspired by the Florentine burial site and combined the impressions with his own fantasy island.

"Villa by the Sea" is another series of three paintings painted between 1865 and 1878. There are again cypresses dominating, surrounding a beautiful classical villa right on the sea. It might sound idyllic, but the mood is far from. This time the cypresses are windswept and a woman dressed in black stands at the water's edge, seemingly in mourning. In the version from 1871-1874 the glowing evening sky is turning darker and the whole painting exudes melancholy, looming threat and transience. The villa itself is in danger of being overgrown with the large cypresses and the bushes.

The iconic status of the Isle of the Dead has obviously to do with its timeless subject matter and our collective fascination with death. We will all take the same journey to this ominous and craggy island and it will be a one-way ride. In the post-irony age when the last nervous laughters of the post-modernists have faded, artists will hopefully dare to take life and death seriously again.

@SteemSwede

@SteemSwede

Sources:

Holzhey, Magdalena (2005). Giorgio de Chirico, 1888-1978: the Modern Myth.

Lenman, Robin (1997). Artists and Society in Germany, 1850-1914.

K. Schmidt et al. (2001) Arnold Böcklin.

You have the power, SteemSwede!

Ehh-HEHH!

I really like your posts.

Your art essays are very intricate and close to impeccable, good sir. Keep 'em coming! Though I know you will. ;)

test

so nice artwork,look like reality

great art..

English

I see articles and photos on your post, have a historical, education, and cultural value of an area. This post is certainly very interesting to add insight in the field of history.

If you do not mind, I will resteem this post in my account. Thanks.

Date:April, 3, 2018Helloo @steemswede Me, @menulissejarah (writing history)

Indonesia

Saya melihat artikel dan foto pada postingan milikmu, memiliki nilai sejarah, pendidikan, dan budaya suatu daerah. Postingan ini tentunya sangat menarik untuk menambah wawasan di bidang ilmu sejarah.

Jika kamu tidak keberatan, saya akan resteem postingan ini di akun saya. Terima kasih.

Tanggal: 3 April 2018Helloo @steeemswede Saya, @menulissejarah (#menulissejarah)

It is a while since your last post @steemswede, but nice to hear from you again

That was really good and thorough analysis of Böcklin's works, I like how you showed the different style of his work and went into details as well as added the opinions of others it is obvious that the works in one or other way call for a reaction, emotion and was an inspiration like for Rachmaninov.

My favorite work is "Isle of the Dead", it is simply made but it can not leave a person without thinking and guessing what Böcklin wanted to tell with his work.