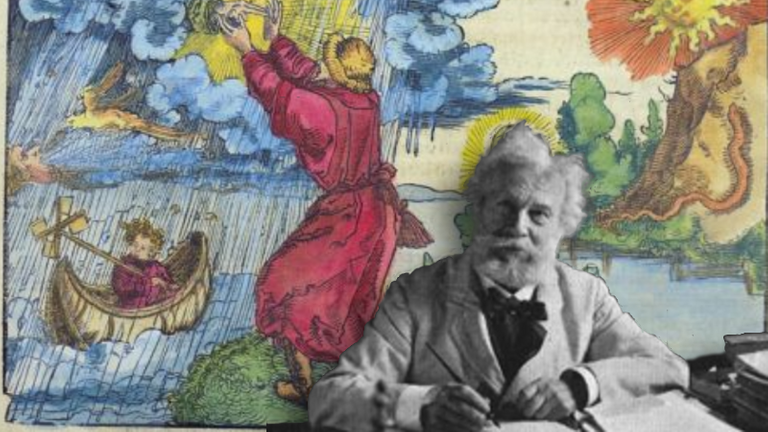

IN "THE ORIGINS of an Occult Masterpiece" (which you can read here) I showed how the creator of the 1888 "Flammarion Engraving" borrowed from two other identifiable artworks to create an iconic new picture (seen right) that has far outshone its forgotten predecessors.

This Steemit post is a short follow-up, because there were some observations I wanted to make, but which I didn't feel were robust enough to warrant inclusion in the main body of research. Nevertheless, they are still interesting, so I'm putting them here, as a sort of postscript.

Note One: The Sun-Moon distance

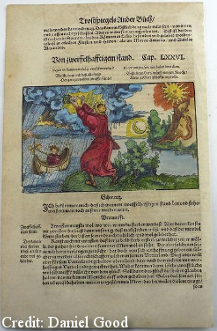

The first thing I wanted to note was that I think there is an accidental but direct proof of the connection between the work of Weiditz and the Flammarion engraver. That is, that when you overlay the Sun in each picture, and then scale them so their circumferences are the same, a relationship emerges that is shown in my animation pictured right.

Unexpectedly, it appears that the distance between the Sun and the Moon is proportionally the same in each picture.

I am only able to illustrate this very approximately, because I can't get my hands on an original of the Flammarion Engraving to take the measurements that would be necessary to prove beyond any doubt that such a relationship exists.

As previously mentioned, engravers routinely used reflective glass to copy details from one picture across to another. So, my guess is that the Flammarion engraver used that method to trace the Sun and the Moon from Weiditz's 1532 original, and (in doing so) inadvertently replicated the proportional distance between them, too.

Note Two: Dante's Inferno

In the Flammarion Engraving's depiction of the workings of the Universe, what appears to be a ring of flames shoots upwards from the bottom of the image (pictured right).

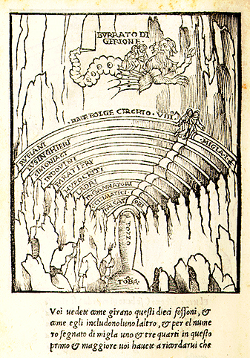

I think there might be a relationship between this element of the Flammarion Engraving, and a 1506 woodcut that illustrated an edition of Dante's Divine Comedy.

You can see it pictured below left. It's a cross-sectional diagram of the structure of Hell, showing the concentric circles of Damnation as they funnel downward into the Earth.

I think that the Flammarion engraver may have taken inspiration from this illustration, and imitated it to provide a suitably fearsome aspect of the ethereal world in his work-in-progress.

(Whether the shapes in the Dante illustration represent flames, I'm not sure. They are ambiguous, and could be fissures in the Earth's crust, one for each circle of Hell.)

One thing is for certain. When you put the Flammarion Engraving and the Dante illustration side-by-side, there is a good angle match between the two, strongly indicative of more than a casual resemblance (pictured immediately below).

Part Three: Closing Observations

The notes in this Steemit post are inconclusive, and are just an addendum to the main work, which revealed the previously-unknown relationship between the 1888 Flammarion Engraving and the 1532 "Apocryphal Nature of Life" by Hans Weidtiz (pictured below left)

In note one, I observed a possible connection between the Sun-Moon distance in each of the two artworks. It's an additional detail to the research, rather than anything completely new.

Note two -- about the Flammarion Engraving's similarities to a woodcut from the 1506 Dante -- is the interesting bit.

The Flammarion engraver's "quotation" from a third artist's work would open onto a new vista of meaning in the 1888 image.

There is a strong conceptual link between the Flammarion Engraving and Dante's Divine Comedy, the plot of which concerns the sorrowing poet's visit to the three realms of the Christian afterlife. The start of this grand tour is Hell, which is reached through a chasm in the Earth's crust.

And finally, the Flammarion engraver's placement of those two details on his new engraving makes perfect symbolic sense.

The "wheel within a wheel" is at the top of the image (suggesting that God is sitting nearby, just outside the picture's edge). And the Dante "flames" are at the bottom of the image.

These two details are in the correct respective positions for glimpses of Heaven and Hell. Not only would this spiritual context be readily apparent to most of Flammarion's contemporary readers (who would be French, and therefore Roman Catholic in at least a cultural sense). It reflects another of the author's lifelong interests: the search for scientific proof of the existence of an afterlife.

The Flammarion Engraving also hints at the spiritual progress made by Dante in his Divine Comedy -- Flammarion's philosopher seems to be entering the celestial realms via Hell, but is presumably hoping to reach Heaven.

Don't get me wrong: I don't think that the Flammarion Engraving is any kind of coded message about Christian mysticism. In my view, what we are perceiving are the thought processes of a first-class intellect, putting together a new artwork in a way that made coherent and satisfying personal sense.

Again though, unlike its predecessor, this Steemit post is speculative. I hope that readers will find food for thought in the above, and that perhaps someone with a professional interest might take up the lines of investigation suggested here.

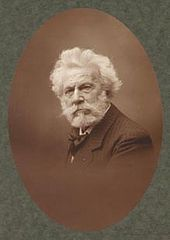

A first step could be to find out whether Flammarion (right) owned books containing the illustrations identified as sources of the eponymous engraving.

If Camille Flammarion owned copies of some or all of these pictures, then surely the Flammarion engraver's inspiration and his identity are both settled immediately.

⦿ All Rights Reserved