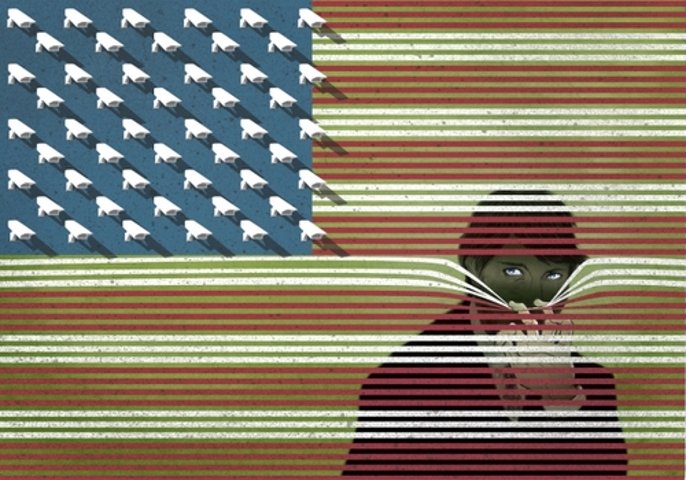

Failing to Connect the Dots on 9/11.

In October 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed into law Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act legislation that established a new framework for American policy, mandating a strict separation of the CIA and the FBI—or, more broadly, between criminal law and espionage. In effect, the Congress erected a “wall” between intelligence gathering and law enforcement after the Senate Church Committee uncovered Cold War–era abuses in U.S. intelligence agency practices. The new law was a procedural mechanism to restrain the surveillance state. Did this wall imperil—rather than protect—American democracy in September 2001? Some think so, but others have their doubts.

The Wall

● The wall stems from an era when legal, social, and bureaucratic restraints on communications between the intelligence sector and law enforcement were thought to be an important limit on governmental intrusion. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) legislation—in the years before the terrorist attacks, but after Congress uncovered a string of errors and abuses in the intelligence sector that encroached on citizens’ rights—strengthened the barrier between intelligence and lawenforcement communications to abate such errors and excesses.

● Why does the wall matter at all? Or, why is there value in separating lawenforcement methods from intelligence activities? The answer lies in the different procedures and forms of inquiry that they use.

● There is a clear distinction between criminal investigations, which are typically conducted under Title III of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 (known as Title III investigations), and national security investigations conducted under FISA. The latter—relating to national security—provides considerably more deference to the executive branch at every step.

For example, while Title III and FISA alike require government officials to obtain ex ante permission from judicial officers for electronic surveillance, courts under Title III (that is, criminal law enforcement) impose a far stricter standard of review before granting authorization.

● Furthermore, after the surveillance is complete, aggrieved parties under Title III who say that the government made an error have substantial rights to challenge the government’s conduct. These rights are nonexistent in the FISA regime.

● Under Title III, the fruits of electronic surveillance can be used in a prosecution only if the defendant is first given copies of the government’s application and the court order approving the surveillance. FISA applications, on the other hand, are generally not disclosed unless ordered by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), which is limited as to when it can order disclosure.

● As a practical matter, defendants in criminal actions rarely have access to FISA applications. Even evidence relating to defendants under investigation for simple domestic crimes, such as drug smuggling, for example, might sometimes be discovered as a collateral part of an intelligence investigation. When that happens, however, the accused drug dealers will usually not understand why it is that the government got the authorization to conduct surveillance in the first instance. The application remains cloaked in FISA’s secrecy blanket.

● An earlier Supreme Court decision in the Keith case, which pitted security concerns against civil liberties during the administration of President Richard Nixon, found that domestic surveillance—whether for criminal or national security reasons—had to fully satisfy the warrant requirement of the Fourth Amendment. The Fourth Amendment prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures and requires any warrant to be judicially sanctioned and supported by probable cause.

● But implicit in this requirement for domestic surveillance is the idea that surveillance of a foreign national for national security purposes might be subject to a less-stringent “reasonableness” standard. Courts around the country soon agreed, holding that surveillance for foreign intelligence purposes needed to be reasonable (but might not require a warrant).

● How do you make such a distinction—between domestic criminal and foreign intelligence activity? Information doesn’t come with a sign on it that says “use me only for foreign intelligence purposes.” And once you collect information, it becomes difficult to deliberately forget it.

● What if, during the course of surveilling a Russian spy, the CIA discovers information about a Russian drug ring? Does it close its eyes to that, or does it share with the FBI? To answer, the courts have developed something that has come to be known as the “primary purpose” test: The lawfulness of surveillance would be determined by the intent, or

purpose, of the investigation. If it were for foreign intelligence, then FISA procedures applied. If it were for anything else, the government had to apply the more stringent Title III rules.

● Some Justice Department officials used the same logic to prohibit consultations and coordination among intelligence and law-enforcement agents and prosecutors. They were afraid that federal courts might look at coordination between law enforcement and the intelligence community and think that they were impermissibly using the relaxed FISA rules to collect evidence for a criminal case.

● The more such consultations occurred, or the more FISA was used to obtain evidence for a criminal prosecution, the more likely courts were to find an improper purpose, they believed. So, they decided that we needed rules limiting consultation—sort of a preemptive strike against

being accused of an improper purpose.

● In July 1995, President Bill Clinton’s attorney general, Janet Reno, approved coordination procedures that “applied in most cases.” As

prominent national security lawyer Scott Glick says, “The guideline limited contacts between the FBI and the Justice Department’s Criminal

Division, in cases where FISA collection was taking place, in order to ‘avoid running afoul of the primary purpose test used by some courts.’”

● On their face, these procedures were stringent: They were meant to limit, but not prohibit, the coordination of intelligence and lawenforcement activity. In practice, they seem to have been interpreted (some say misinterpreted) as a strait jacket.

● As Glick rightly summarizes: The “foundations of the FISA wall lie in the ‘primary purpose’ test.” The Department of Justice (DOJ) acted as a barrier to communications so that it could tell the court that a wall existed. In other words, the wall was a procedural barrier that made it impossible to use intelligence for law-enforcement purposes—and

therefore allowed the Office of Intelligence Policy and Review (OIPR) to reassure the courts that intelligence collection was exclusively for intelligence purposes.

● One critical procedural aspect of the rules was the requirement that specialized requests for surveillance had to go through FBI headquarters and the OIPR at Main Justice. OIPR was both the wall and a gatekeeper— making sure that the FBI just didn’t talk to the CIA, and vice versa.

● Why? What could account for this attitude? Some can rail against ignorance or malfeasance, but the likely answer is more prosaic. The creation of the wall, and rules about it, erected a compliance culture within the FBI and DOJ, where failure to follow procedure resulted in adverse personnel actions.

The 9/11 Commission

● The congressionally authorized 9/11 Commission reviewed the function of the wall prior to the terrorist attacks and painted a depressing picture of bureaucratic rigidity: “Over time,” the commission report concludes, the OIPR and the FISC “began to see mere contacts between the FBI and the Criminal Division as a proxy for improper direction and control. Significantly, OIPR viewed its role primarily as an officer of the FISA Court and therefore responsible for stewardship of the court’s responsibilities.

It viewed its role as an advocate for its institutional clients [that is, the

FBI] as secondary.”

● In November 2000, the FISA Court added a requirement that no one in the FBI or DOJ—including persons working solely on intelligence investigations—could see FISA material before signing a form acknowledging that they understood the restrictions on sharing any information they obtained.

● This form assured that information sharing would essentially come to a halt, because agents feared that they would lose their jobs if they shared any intelligence information with criminal investigators. Although this “wall” of restriction formally applied only to FBI intelligence collection, it also came to be adopted by other intelligence agencies, again out of an overabundance of caution.

● Part of what the 9/11 Commission said about that phenomenon is as follows: “The National Security Agency (NSA) also placed restrictions on

the sharing and use of information it collected. Initially these restrictions merely governed the use of its reporting in criminal matters. In December 1999, however, the NSA began placing new, more restrictive caveats on its bin Ladin–related reporting. These caveats precluded sharing the information contained in these NSA reports with criminal prosecutors or investigators without obtaining OIPR’s permission.”

● The NSA couldn’t always tell exactly what source it had gotten information from—a restricted FISA source or an unrestricted non-FISA source. Because of this, in the run-up to 9/11, the agency concluded “that there was no administratively easy method to determine which of its reports were from FISA-based collections,” according to the 9/11 Commission. “Thus, caveats were added to all NSA counterterrorism reporting that precluded sharing the contents of the reports with criminal investigators or prosecutors without first obtaining permission from NSA’s general counsel.”

● Consider, for example, what happened to the agency’s surveillance of two of the 9/11 bombers. As the 9/11 Commission tells us, “In December 1999, the NSA picked up the movements of Khalid al Mihdhar, an individual then identified as Nawaf Mihdhar, which linked

him to a terrorist facility in the Middle East. Mihdhar was tracked to Kuala Lumpur, where he met with other then-unidentified individuals. Some photographs were taken of these men on the streets of Kuala Lumpur. The surveillance trailed off when three of them moved on to Bangkok, on January 8, 2000.”

● Those pictures became relevant to the FBI’s pre-attack criminal investigation in July 2001. Unfortunately, as the 9/11 Commission found, the NSA reports contained caveats that their contents could not be shared with criminal investigators without the OIPR’s permission.

● The failures of 9/11 were less about statutory language and more about human fears and hesitations—an abundance of caution and the inability of bureaucratic organizations to adapt to discrete circumstances. Even more than a wall, the law created a space—a dangerous void—between the government’s criminal and intelligence sides of the house.

The Aftermath of 9/11

● The reaction after 9/11 was swift. In late September 2001, the executive branch sent Congress draft legislation proposing changes to FISA’s certification requirement for electronic surveillance and physical search applications. In the area of foreign intelligence collection, the prescribed change was from “the purpose” to “a purpose.”

● In explaining its rationale, President Bush’s administration stated that such a change would “eliminate the current need continually to evaluate the relative weight of criminal and intelligence purposes, and would facilitate information sharing between law enforcement and foreign intelligence authorities which is critical to the success of anti-terrorism efforts.”

● Associate Deputy Attorney General David Kris testified at a September 24, 2001, hearing on the legislation that “the animating purpose” of the change was to “bring those two sides together, allow for a single unified, cohesive response, and avoid splintering and fragmentation.”

● Even then, some civil libertarians expressed concern. Critics of the legislation thought that simply requiring that foreign intelligence be “a purpose” of the collection was too big a blank check for the government to make use of FISA. As a compromise, the law was changed from “the purpose” to “a significant purpose.” Buried in this change was a legal determination and also a cultural critique.

● Congress was calling for greater coordination and less concern about protective legal standards. So, as a legal matter, that is where matters

fell after 9/11.

● The FISA Court of Review, as an appeals court for the FISA Court itself, summarized the new standard. It said that the FISA Court should not deny an application if “ordinary crimes” were “inextricably intertwined with foreign intelligence crimes.”

● For example, a terrorist who commits bank robberies to finance terrorist activity could be targeted using FISA’s less-stringent standards. As long as foreign intelligence was a “realistic option,” using the relaxed FISA procedures was acceptable.

● On the other hand, the review court said that the “FISA process cannot be used as a device to investigate wholly unrelated ordinary crimes.” As a result, to meet the new “significant purpose” test, the government need only “articulate a broader objective than criminal prosecution when applying to the FISA Court for authority to conduct surveillance. Such broader objectives could include stopping an ongoing conspiracy.”

Questions to Consider

Which is more important in controlling government: law or culture? Why?

We often overreact to crisis. Did America overreact to the Church Commission? To September 11th? To both? To neither?