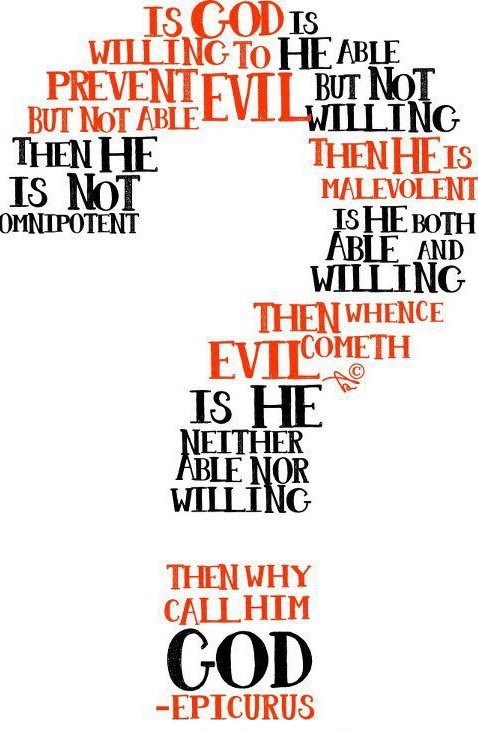

One of the most common objections to theist claims is the so-called "problem of evil." The argument goes: An all-good, all-knowing God would not allow evil to exist in a world of His creation. Evil does exist, therefor an all-good, all-knowing God cannot exist. This is a big sticking point for a lot of people, though I've always had a hard time understanding why; it seems to be a very shallow way of looking at the subjects of good and evil, and the mind of God. Libertarians, however, should have an easier time grappling with this issue, with their understanding of unintended consequences and social complexity. I'll attempt here, then, to resolve this problem of evil using libertarian language.

There are two components to the problem of evil. The first, evils that occur due to human choice, is relatively easy to handle. The second, evils that occur outside of human control, is a bit more difficult. I'll give the first a brief treatment, and then move on to the second.

A central tenet of Christian theology is the doctrine of free will. God gave man the ability to choose between good and evil. If God simply wanted robots with no ability to sin, then their apparent "goodness" would have no value. Out of His love, he gave us the ability to choose to love him or not, because genuine love can only be given freely, not commanded or forced. Most libertarians also believe in free will. If we did not, it would be meaningless to judge an action as ethically right or wrong, and it would make no sense to punish a murderer or thief. So if we take free will as our premise, it's clear why God would allow evil committed by human beings. To disallow it would violate the free will that is necessary for moral acts and choices to even be possible. Mass murder, genocide, slavery, and taxation are all evils committed by mankind exercising their free will, and cannot be "blamed" on God or taken as evidence of His non-existence.

But what about the second component of the problem of evil, that is, evils that occur outside of human choice? This requires a more in depth explanation, and this is where I think libertarians in particular are better equipped to understand to subtlety of the answer.

For many of us, when we begin to learn libertarian theory and economics in particular, it is like putting glasses on a person with blurry vision. Suddenly, the world is brought into focus, and things that were obscured or not seen at all are viewed with clarity. Some things that at first glance may seem indefensible, even evil, can be seen in an entirely different light.

Take, for instance, child labor. People living in a modern industrialized society can easily say that no child should be made to work, and only a bad parent would require their child to do so. But even a cursory understanding of economics, or simply the idea of cause and effect, shows us that bans on child labor in third world nations results in starvation for the child and their family or child prostitution. The child doesn't work because their parents are cruel; they work because they have no better options.

Or consider the ruthless dictator. It's easy enough to hear about atrocities committed against his own subjects and declare that "So-and-So must go!" But a quick glance at even recent history will show what often comes of such interventionism: the dictator will most likely be replaced by either a worse dictator or a situation of rival factions warring over who will fill the power vacuum. Neither outcome works out very well for the citizenry that the intervention was meant to help.

As we gain understanding of cause and effect in the world, we are able to take a wider view. We can see that some situations or events which may on their face appear to be clear evils should not necessarily be artificially altered, lest we cause a greater evil. If we, with our limited minds, can see these phenomena, how much more would be understood by an infinite mind?

In the examples of child labor and the dictator, we are considering situations that we, as outside observers, did not directly bring about, but into which we have the potential to intervene. Taking a broader perspective, we can conclude that, although an intervention may be possible, it is wiser in the long run to take a hands-off approach. (Here, of course, I'm referring to political intervention and the use of force; this is not to suggest that individual voluntary action such as charity is unwise or harmful in these situations.) Similarly, in the case of such things as natural disasters, disease and famine, the existence of which humans have little control (to the extent that they are naturally occurring and not the result of human action), and it is difficult if not impossible to see any good that may come of them, it may be that God, while He has the ability to intervene and prevent them, chooses to allow them due to his infinite perspective and understanding of all cause and effect relationships.

In Christian apologetics, it's often said that God will allow certain evils in order to bring about a greater good. This may not initially seem like a very good answer, but the libertarian himself will make use of the same sort of reasoning to argue against intervention in apparent evils in this world.

If the cause of all existence can see the entirety of space and time, in full and perfect understanding of it, then it is not unreasonable to assume that certain events that seem to us, in our minuscule understanding, to be incomprehensible evils, may be allowed by an infinite mind to accomplish a fundamentally good end.

It is impossible for mere mortals to unravel the entire knot of human history to show why each event occurs in the grand scheme of things. But the fact that even we, as we gain understanding and wisdom, can unravel small knots, shows that for a being of infinite understanding and wisdom, and perfect knowledge of all events, the large knot would be no knot at all. It would be, rather, the image of a grand and infinitely complex design. Our inability to comprehend it all in this life is simply not a strong argument against the existence of God.

Umm, what? I thought God was all-powerful. He can create the universe out of nothing but you're quite sure he can't figure out a way to allow both free will and not have significant evil just because you can't figure one out?

I mean, I can even figure out such a way. I can't choose to become invisible or choose to end millions of lives just because I'm having a bad day, but Hitler had enough free will to kill millions of people. Surely God could have given him a bit less. That would certainly still seem to be enough free will to permit moral acts and choices to be possible.

What kind of all-powerful being needs people like you to make sad excuses for his readily apparent bad choices?

Well, I thought the free will argument was the easier to understand, so I didn't spend much time on it, but I suppose I must go into it.

Firstly, "enough" free will? A "bit less" free will? As in, a certain level of limitations on a human being's ability to make free choices? Let's see what that might look like. Let's make man free to make his own choices except for the choice to murder. Since man no longer has the ability to choose to murder, is murder still wrong? It would be odd to say so, as the possibility of murder no longer exists. How about the ability to steal? Is theft still wrong if we cannot choose to steal? How about lying? Or cheating on your spouse? What you're suggesting is a totally arbitrary line that you yourself deem fit to be drawn on the limitations of man's freedom. Free will does not exist if we are not free to choose wrongly, and the very concept of wrong choices disappears when we no longer have the ability to choose them.

If a slave is free to walk to the outhouse by himself, but not free to leave the plantation, you would not say that he is free "enough", or that he has a "bit less" freedom than he could have. The very existence of limitations on his freedom means he is not free. You can not dole out free will piecemeal.

And you mentioned "significant" evil. That's a pretty vague distinction. At what point does evil become significant? Is it when it reaches some kind of Top Ten Evil Things In The World list? What if we removed those top ten evil things? Would significant evil still exist, or would the next group of evil things, formerly designated as less significant, become the new Top Ten? Or what if ten new evils were introduced that suddenly seemed worse than the previous Top Ten? Would those formerly "significant" evils suddenly become less so? You're speaking in arbitrary language, and missing my point entirely.

Finally, God doesn't need me to defend him. He's not like Tinkerbell who will cease to exist if no one believes in Him anymore. I'm writing things like this not to defend God, but because I want to help clear up mistaken beliefs people have about Him. I am interested in the truth, and spreading the truth, for the sake of my fellow man.

These are all equivocations, and I think you know it.

There are lots of limitations on a human being's ability to make free choices. I cannot choose to be invisible. And I cannot even choose to murder someone. I know precisely what prevents me from choosing to be invisible, but I have no idea what prevents me from choosing to murder someone. But I know I cannot do it.

Is it a moral issue that I choose not to murder someone even though, for reasons I don't understand, I can't choose to murder someone?

And what if I do murder someone. How do you know I could have chosen not to?

And if you want to argue that I can't tell what a significant evil is, then you can't either. In that case, we are incapable of accurate moral judgment. In that case, we cannot conclude accurately that God is good or worthy of worship.

But the thing that is the most absurd in this is that your defense of God's toleration for evil is based on limitations on what God can do. What could possibly be the source of these limitations on God? Are you really saying that God is just powerful enough to create a universe with this level of evil and unfortunately cannot create a world with more good and less evil? If so, because of what?

I'm not equivocating. I'm trying to demonstrate that you are using arbitrary and vague language to try to find fault with a God you don't seem to believe exists (which, by the way, is itself an example of equivocating... Check your definitions). You seem also to not understand what free will actually means, by the very fact that you're advocating that the allegedly non-existent God place limitations on the free will that He gave us. Let me help you. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines free will as: "the ability to choose how to act; the ability to make choices that are not controlled by fate or God". So for God to place limitations on man's free will would effectively nullify it.

The actual fact of God's existence is a separate issue that must be taken on its own, but assuming that He does for the sake of argument, as we are both doing here, then He is all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good (these are necessary qualities derived from Aquinas' proof from motion). What you are suggesting here, then, is that you can envision or devise a more perfect arrangement for existence than an infinite mind. This was the entire point of the second part of my original post. An infinite mind is in full knowledge of all causal relationships, and so things that may seem to be "too much" evil or "not enough" good in this world are derived from our imperfect understanding of events. You say that my "defense" is based on limitations on God's power. I haven't said anything of the sort. I'm trying to explain that God made things the way they are for a reason, and that our minuscule understanding of it is no proof that it is therefor a failed system. That part has to do with evils not caused by man's exercise of free will. What you seem concerned with are evils that are committed by man exercising his free will, against other men. This is not a necessary component of the grand design of God, but a consequence of our free choices. And as I stated before in my original post, God gave us this free will so that we would have the ability to genuinely choose the good (and, in so doing, choose Him). If that free will was taken away, a genuine choice toward the good would be impossible. We would simply be robots doing whatever God forced us to do.

I know people don't like to be pinned down to solid positions, because it leaves them vulnerable, but for a productive discussion to take place I need to know where you're coming from. So, do you believe in free will? And I don't mean should people have free will, but do they actually have it? You say you don't have the freedom to choose to be invisible, and that's true; we are constrained in our actions by the laws of nature. But you seem to think you don't actually possess the ability to choose to murder. But other people apparently do. So do you have less free will than some other humans? Or does the thought simply repulse you and so you can't conceive of making that choice?

You're making this way too complicated. It's really very simple:

I can't choose to become invisible. Does that mean I don't have free will? Surely God could have created a world in which I could choose to become invisible.

If the God you believe in exists, he chose exactly what I, and everyone else, can and cannot do. Hitler could kill millions of people because God chose to put that within the scope of his decision-making. I cannot choose to become invisible because God chose to put that outside the scope of my decision-making.

How can you judge the God you believe in as worthy of worship when he chose to make it possible for Hitler to decide to kill millions of people? What argument can you possibly use that he had to give Hitler that choice that doesn't also show that he has to give me the choice to become invisible -- which he did not do?

(And, of course, you are right. I don't believe that the God you believe in exists, or even could exist. One of the reasons is all the obvious contradictions, such as this very one.)

I apologize for making it too complicated for you. You seem to be having trouble catching my meaning, so I feel we are just repeating ourselves. Let me try to approach this in a different way.

For God to create such a thing as human kind, He would have to create a physical world, governed by physical laws, yes? So the physical laws of the universe are of His creation. According to those physical laws, humans cannot become invisible. If He wanted to create a world in which His creations could do anything they could possibly conceive of, He would essentially be filling the universe with little Gods. Without any limitation on their abilities, they would be indistinguishable from Himself. What would be the point of creating them, then? Instead, God created a physical world governed by physical laws, and physical beings within it who are subject to those laws; He created something outside of Himself, thereby creating the possibility that His creations could come to know and love their creator. Invisibility is not a power granted to us within the confines of the physical universe, but that has nothing to do with the issue of free will.

Imagine an RPG (not sure if you play video games, but you strike me as the sort that would), the Elder Scrolls series for example, as that's my favorite. The world is set up with physical laws that govern it, like gravity and the passage of time, and define an order to what is possible and what is not. Without these underlying rules, the game would make no sense, it would be unintelligible and therefor unplayable. Given the world as it is set up, you're free to play as you wish. You can be an evil character, killing innocent villagers for no reason, raiding merchant shops, cheating your guild masters, etc., or you can choose to help other characters on their missions, respect the rights of innocents, and so forth. The fact that you can't turn your character into an artichoke if you wish has no bearing on your free will in the moral sense. Likewise, your inability to become invisible in our actual world is simply a consequence of the way that the universe is set up. Without governing physical laws, there would be no intelligible space for "game play". This has nothing to do with your free will to act morally or immorally in the world in which you are placed.

Of course, in the Elder Scrolls world there are ways to become invisible: potions, scrolls, etc. In the parameters set up in that world, it's a possibility. In our world, we have a different set of parameters. I'm not aware of any technology currently in existence that would grant us invisibility. I'm pretty sure that's not your point, though. I think you're trying to say that physical limitations in this world are themselves restrictions on free will. This confusion of yours was probably my mistake in not specifically indicating that by free will, in this case, I meant moral free will. To compare the freedom to choose to be invisible and the freedom to choose to kill are two separate things. One is a physical ability, the other is a moral choice. If you're trying to make the point that physical limitations are limitations on free will, then I would reiterate that those physical limitations are consequences of the existence of a physical universe in which such a thing as man kind is possible, and in which moral choices can exist. You're comparing apples and oranges.

You keep bringing up Hitler, and I've been trying to tackle that subject in a broader sense, but I'll go ahead and address him specifically. Hitler entered into power through widely recognized, legal, democratic means, and he used his position not to directly kill millions of people, but to order many others to do so on his behalf. This means that it wasn't really Hitler who directly killed millions of people, but rather many people exercising their own free will to commit murder or support such acts. But if I'm reading you correctly, you're just using Hitler as a placeholder for those who commit evil acts, so my original argument remains, which you claim I have not laid out. But I've already laid out my argument for why God grants us free will. To put it as simply as I possibly can, God gives us free will so that we have the ability to choose the good. This freedom necessitates the ability to choose evil. If you don't remember, go back and reread. I'm repeating myself here again and again on this point, and you seem to be pretending I never said anything about it. If you don't think it's a good argument, please explain why. If the point of human life on this earth is, as the Christian believes, to freely choose God (and therefor the good), then the possibility to not choose Him must exist. Hitler, his followers, and others throughout history are examples of people choosing evil.

Oh, haha, silly me, I totally overlooked the fact that you once again failed to answer my direct question as to whether you believe that mankind has free will or not. Like I said before, I know people often don't like to be pinned down to definite positions, lest they expose themselves to criticism, but as this is central to the discussion at hand, and I have already made clear my own position, I think it's relevant for you to state your own. After all, if you are opposed to my position, then you must therefor hold an opposing position, and for fruitful discussion to take place I should at least know what this position is. So, do you believe in free will? If not, why not?

all comes down to answer the question: is there unnecessary suffering in the world? If you think not, that all suffering is necessary and has a purpose, then it becomes easier for you to believe in a god. Otherwise, if you identify unnecessary suffering in the world as children being raped, starving, etc., then like me you will never understand the belief in a good God.

I don't believe that all suffering is necessary, and I wouldn't need such a belief in order to believe in God. As I said, the problem of evil has never been much of a sticking point for me. I believe that God exists because reason dictates that He must. If you want an example, Aquinas' argument from motion is the most clear and convincing for me. But if you want to bring up things like children being raped, that is a reflection on man's choices. It's not necessary at all. It is a result of free will. As I said in my post, the problem of evils that result of man's choices is pretty easy to understand. That's why I didn't spend much time on it, and instead focused more on the harder question of evils that occur outside our control. Do you really not grasp the idea that God gives us free will in order to make moral choices possible, and that means that people have the ability to choose to do evil things like rape children? The fact that people choose this is no argument against God at all.

If not all suffering is necessary, such as the rape of a child, so therefore free will is also not necessary, it would suffice limited freedom, which allow only the existence of the necessary suffering and would save children from being raped.

Free will is necessary for the existence of free choices. We cannot freely choose the good without the freedom to choose evil. If we did not have the ability to freely choose, it would be meaningless to ascribe morality to them. I feel like I'm repeating myself. Did you read the third paragraph of my post? If so, what exactly doesn't make sense about it? Or do you not believe in the existence of free will?

I agree with you that in the field of thoughts, ideas, we should really be 100% free to think what we want because the simple thinking is unable to cause unnecessary suffering. But in the field of actions, many of these ideas can and should be restricted, without prejudice to any free thinking.

Are you referring to the restriction of human action in society? Because that's a different issue (though an important one) from metaphysical free will. I am asking whether you believe that mankind actually has the ability to choose his actions freely, not whether or not they should be able to. And as to your point below, about people who believe in the necessity of police (I am not one of them), and the apparent contradiction between a belief in free will and the belief in the necessity of restricting man's free choices, that is related, and I attempted to draw a correlation between the libertarian idea of free will and the Christian idea of free will. Apart from whether you believe free will exists at all, I'd also like to ask, are you a libertarian/anarchist?

I am a libertarian

Then, as a libertarian, do you believe that mankind has free will? Not that he should have free will, but that he actually does have free will? As in the ability to make choices, in action and in thought?

Our ability to make choices is limited to the circumstances, our brain state (children, crazy and drunk are not sober to make choices). And since time and space are no longer separate entities but are entangled in the space-time fabric, I seriously suspect that what we call free will is just an illusion. And research indicates that magnetic fields applied in your brain can interfere with your choices between raising the right or left arm, for example.

https://steemit.com/discussion/@discernente/babies-do-not-have-free-will

So you lean toward determinism, then? You believe that our actions are not the result of free choice, but rather the result of our biology, chemistry, and ultimately quantum fluctuations? If that's the case, then we can't pass moral judgement on the actions of any person, as he was simply acting according to his biology and had no choice in the matter. In fact, according to determinism, we cannot judge truth claims at all, as our brain states themselves are merely a product of material circumstance. Therefor, the words that you and I are writing, the discussion we are currently having, has no meaning whatsoever. This line of reasoning seems problematic to me, but if you believe this, then why would you be engaging in debate with me at all, much less about moral values in the world?

Those who believe in the necessity of the police, in practice does not believe in the necessity of free will.

I've noticed that too. Your point being?

My point is that there is a discrepancy between what is defended as a value in theory, and what is done in practice to restrict that freedom. In practice the theory is another.